On the third Thursday of the month right on schedule NOAA issued what I describe as their Four-Season Outlook. The information released also included the Mid-Month Outlook for the single month of April plus the weather and drought outlook for the next three months. I present the information issued and try to add context to it. It is quite a challenge for NOAA to address the subsequent month, the subsequent three-month period as well as successive three-month periods for a year or a bit more.

It is very useful to read the excellent discussion that NOAA issues with this Seasonal Outlook.

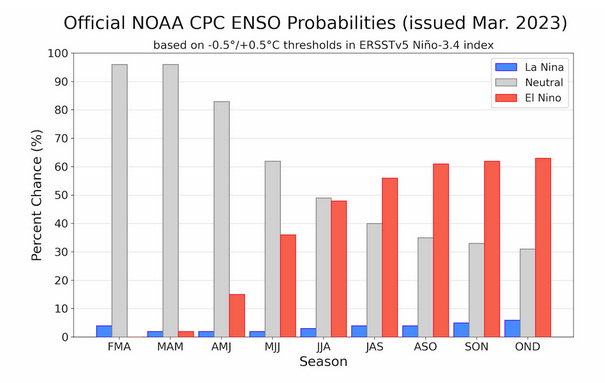

Ocean conditions no longer reflect La Nina but the atmosphere still has some lingering La Nina characteristics. ENSO Neutral will be the prevailing condition but its impacts are less during the Spring and Summer Seasons. The Southwest Monsoon may start late. The outlook partially reflects El Nino conditions beginning in the Autumn of 2023. We may see more El Nino impacts reflected in the Outlook next month if the confidence in an El Nino gradually increases as we pass through the Spring Prediction Barrier (SPB).

| The current weather report is always available at econcurrents.com To return to this article, hit the return arrow in the upper left-hand corner of your screen. |

Let’s Take a Look at the Mid-Month Outlook for April.

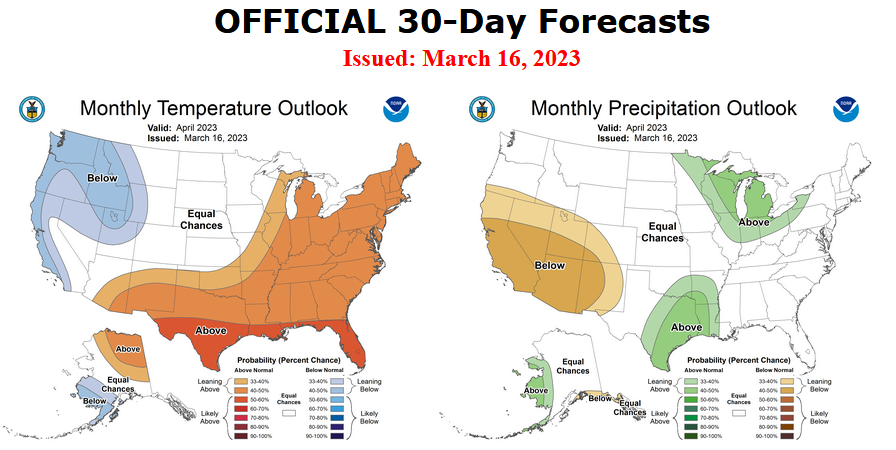

Combination Mid-Month Outlook for April and the Three-Month Outlook

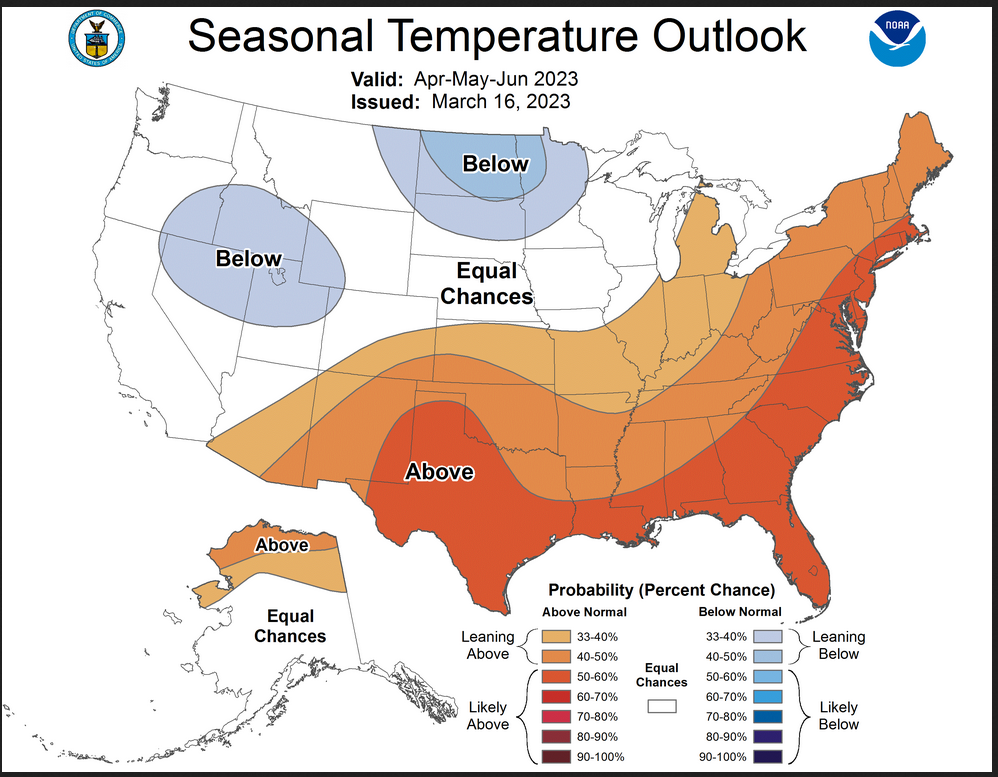

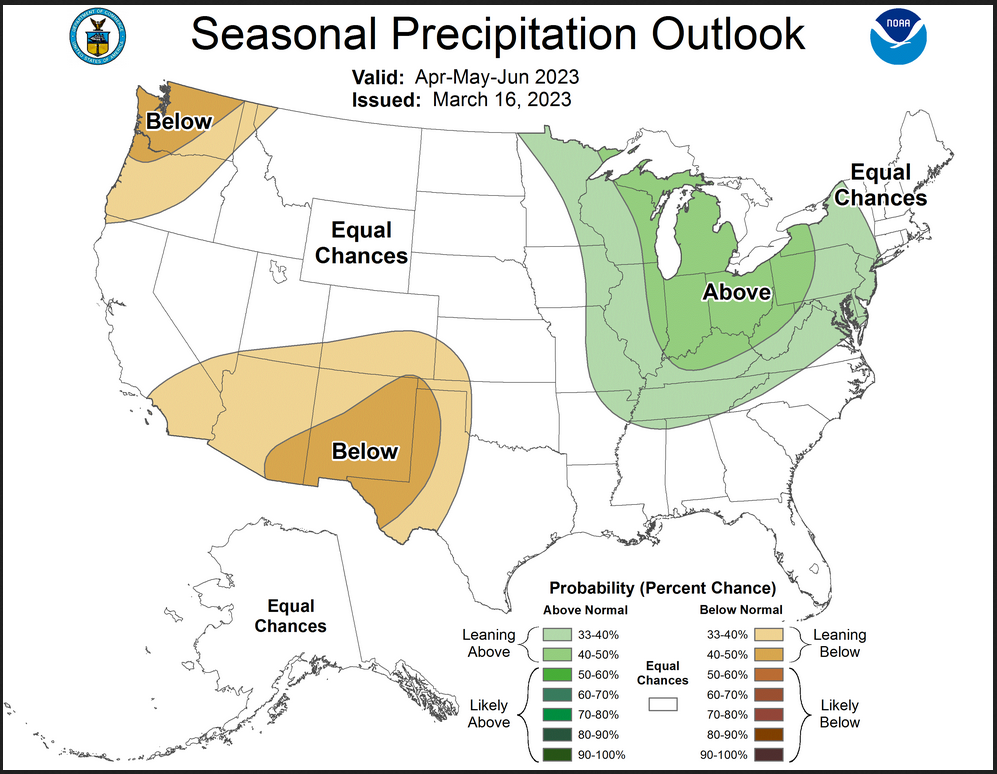

The top row is what is now called the Mid-Month Outlook for April which will be updated at the end of March. There is a temperature map and a precipitation map. The second row is a three-month outlook that includes April. I think the outlook maps are self-explanatory. What is important to remember is that they show deviations from the current definition of normal which is the period 1991 through 2020. So this is not a forecast of the absolute value of temperature or precipitation but the change from what is defined as normal or to use the technical term “climatology”.

| Notice that the April and three-month outlooks are fairly similar. But they are different in important ways so there is a predicted difference as the three-month period evolves. |

| For both temperature and precipitation, if you assume the colors in the maps are assigned correctly, it is a simple algebra equation to solve the month two/three anomaly probability for a given location = (3XThree-Month Probability – Month One Probability)/2*. So you can derive the month two/three outlook this way. You can do that calculation easily for where you live or for the entire map. |

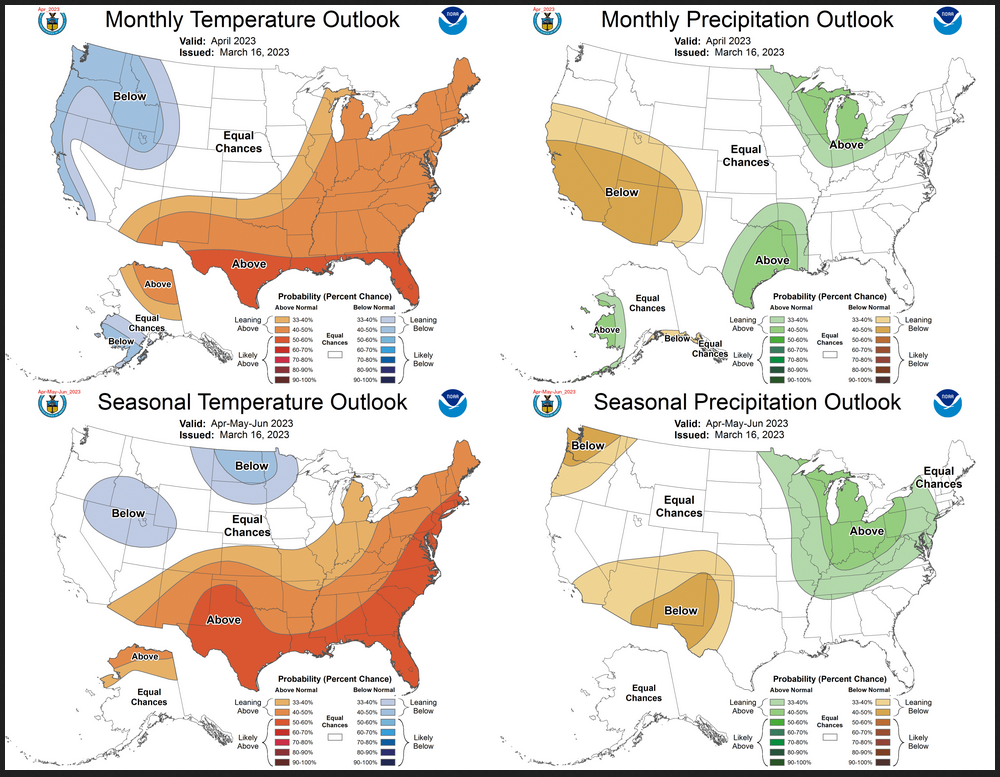

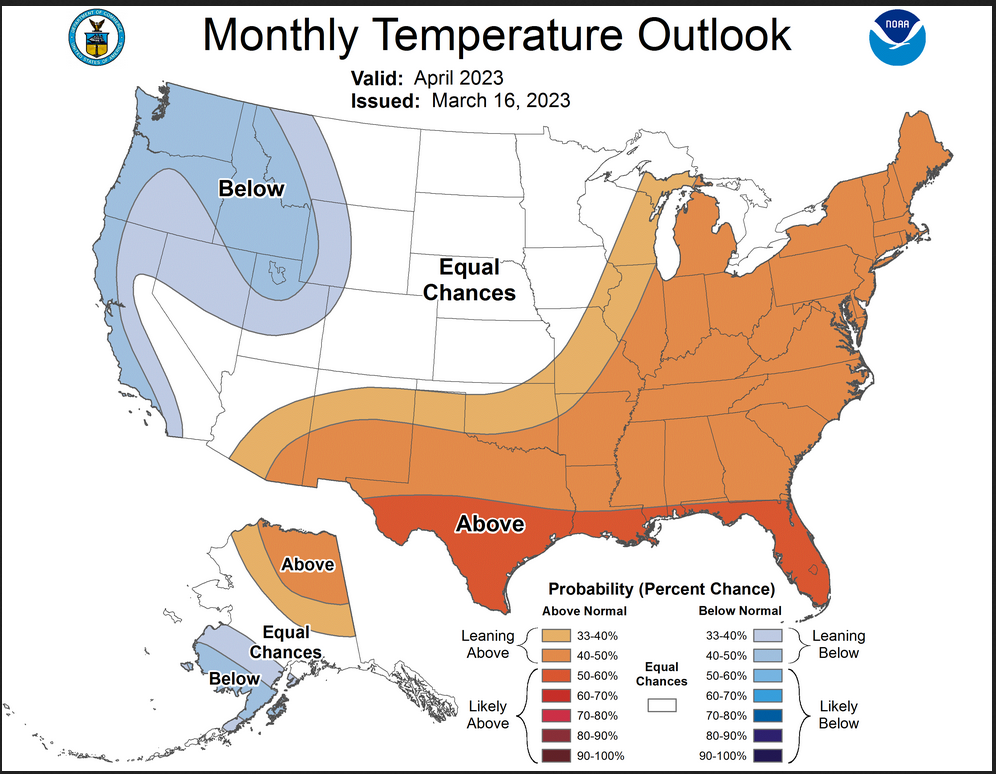

Here are larger versions of the Temperature and Precipitation outlook maps for the single month of April

The maps are pretty clear in terms of the outlook.

And here are large versions of the three-month AMJ 2023 Outlook

First temperature followed by precipitation.

The maps are larger versions of what was shown in the first graphic that had smaller versions of all four of these maps.

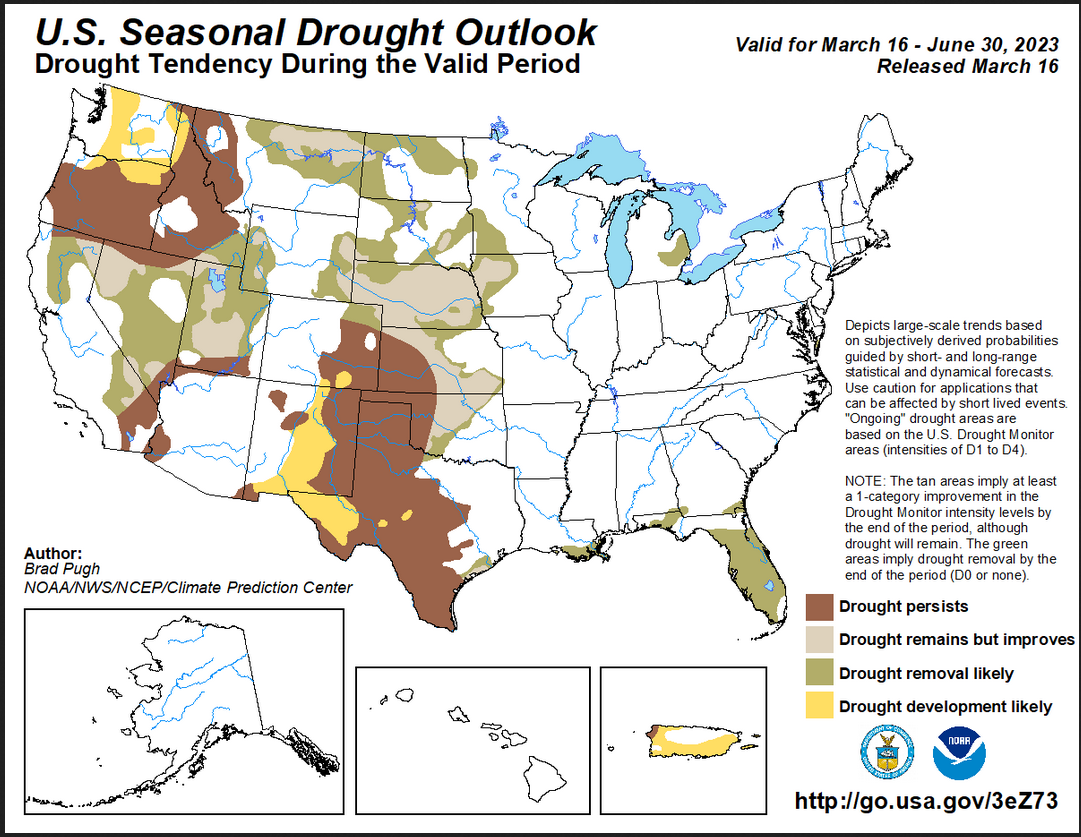

Drought Outlook

| The yellow is the bad news. And there is some of that. But the area with drought improvement is very much larger. There are some dry areas predicted but the initial conditions is limiting where the drought is expected to get worse. |

Short CPC Drought Discussion

Latest Seasonal Assessment – According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, drought coverage across the contiguous U.S. (CONUS) peaked at 62.95 percent during late October 2022. Since that time, a steady decrease in drought coverage and intensity occurred across much of the West, northern Great Plains, and Midwest. Drought coverage for the CONUS is at its lowest since the summer 2020. Based on an above-average snowpack and a continued wet pattern into the latter half of March, additional drought removal or improvement is forecast throughout much of California and the Great Basin. Initial dryness heading into the spring and the April-May-June (AMJ) outlook favoring below-normal precipitation support persistence and development across the Pacific Northwest and northern Rockies. An increasingly wet climatology during the spring favors removal or improvement for the northern to central Great Plains and Midwest. In addition, the spring melting of a deep snowpack across the eastern Dakotas and western Minnesota should contribute to improvement or removal. Elevated probabilities for below-normal precipitation in the AMJ outlook support broad-scale persistence across the southern high Plains with development for parts of western Texas and southern to eastern New Mexico. Removal is the most likely outcome for Florida, based on widespread, heavy precipitation during mid-March along with a wet climatology during June. The Northeast, Alaska, and Hawaii are forecast to remain drought-free through the end of June, while development or persistence is likely for parts of Puerto Rico.

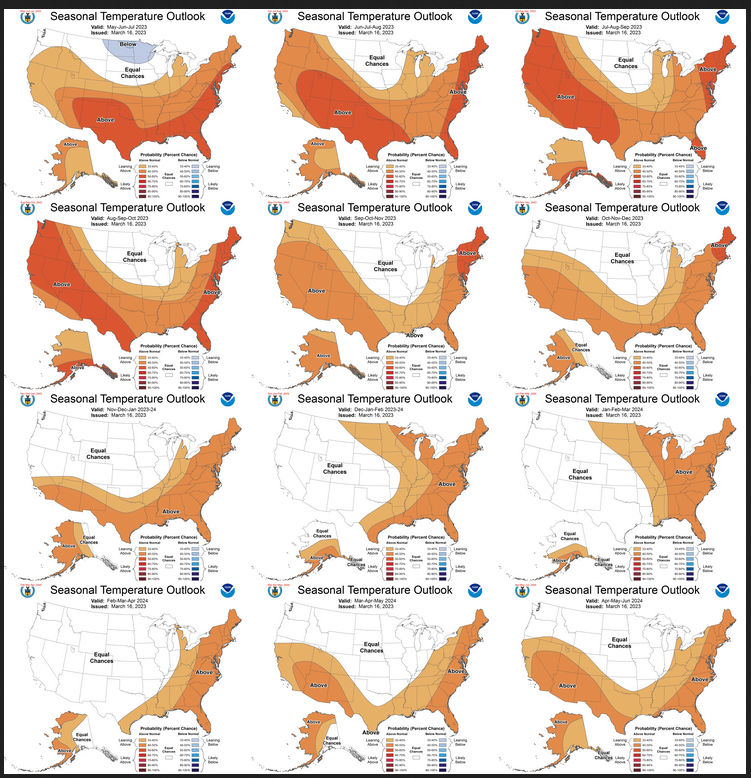

Looking out Four Seasons.

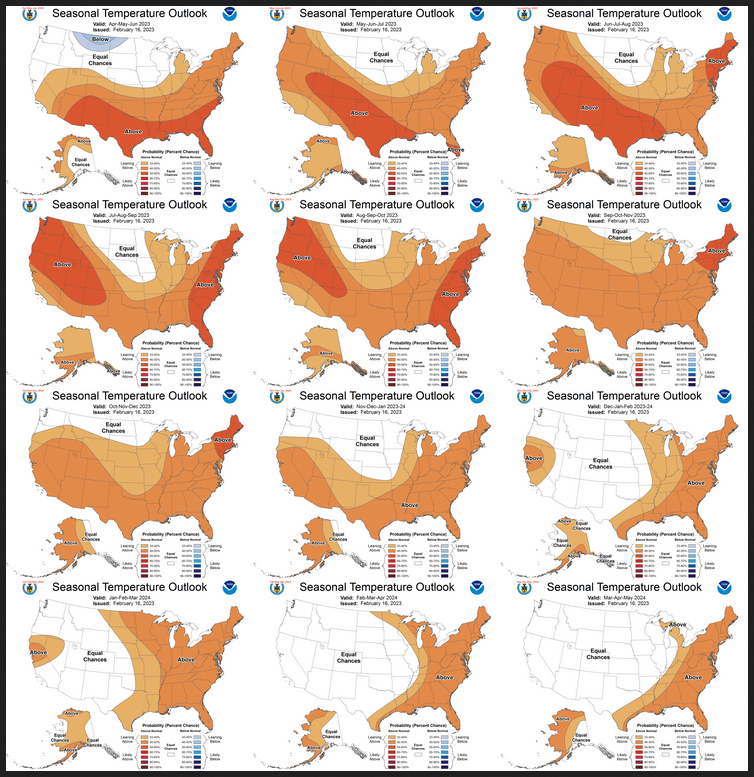

Twelve Temperature Maps. These are overlapping three-month maps (larger versions of these and other maps can be accessed HERE)

Notice that this presentation starts with May/June/July 2023 (MJJ since AMJ is considered the near-term and is covered earlier in the presentation. The changes over time are generally discussed in the discussion but you can see the changes easier in the maps.

| You can see the major change in NDJ 2023/2024 which is similar to the seasonal outlook issued last month. It seems to be related to the evolution of the ENSO state to an El Nino winter. But predictions are tempered by what is called the Spring Prediction Barrier (SPB). HERE is a good reference for more information on the SPB. |

Comparing the new outlook with the prior Outlook,

The 12 temperature maps issued last month.

I have been showing the current set of outlooks with the prior set side by side. But I think the images are too small for most to be able to work with. I do the analysis so you do not need to but if you choose to do so the best way is to print out both maps. If you have a color printer that is great but not needed. What I do is number the images from last month 1 – 12 starting with “1” and going left to right and then dropping down one row. Then for the new set of images, I number them 2 – 13. That is because one image from last month in the upper left is now discarded and a new image on the lower right is added. Once you get used to it, it is not difficult. In theory, the changes are discussed in the NOAA discussion but I usually find more changes. It is not necessarily important. I try to identify the changes but believe it would make this article overly long to enumerate them. The information is here for anyone who wishes to examine the changes. I comment on some of the changes from the prior report by NOAA and general changes in the pattern.

| I found it hard to describe but the pattern starting in SON 2023 is different than last month for about three three-month periods. I was not sure how to interpret this change. |

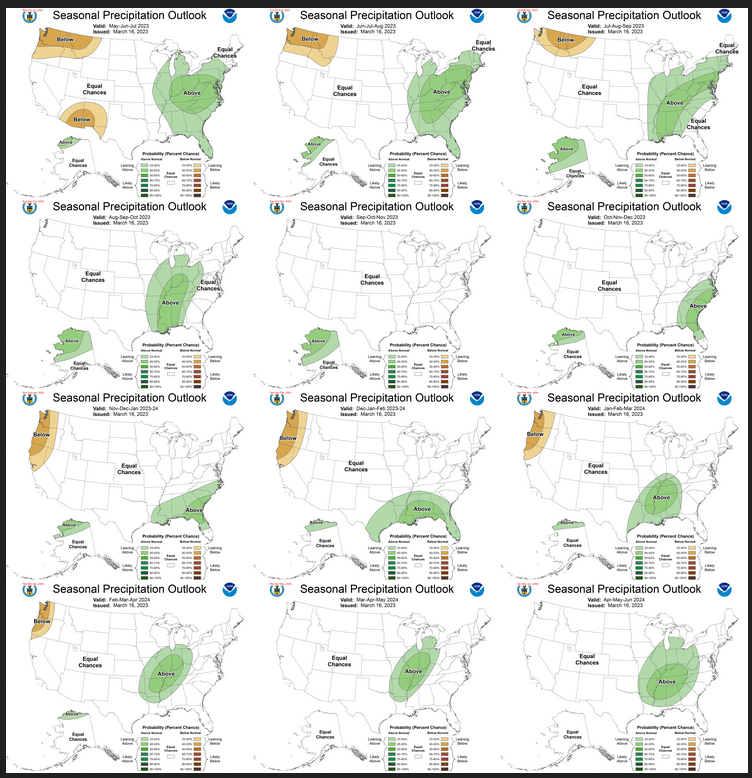

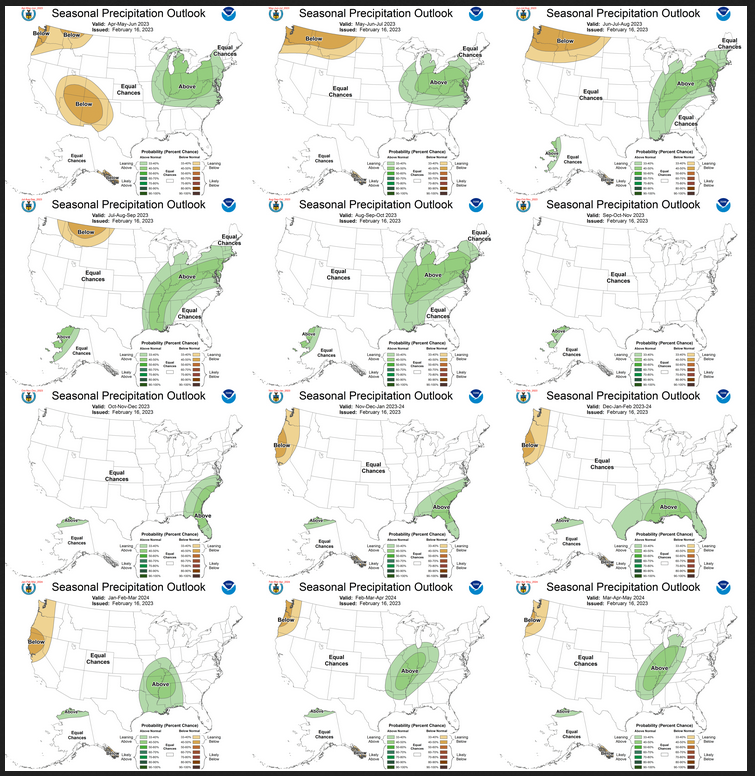

Now the Twelve New Precipitation Maps

Similar to Temperature in terms of the organization of the twelve overlapping three-month outlooks.

| The change in the pattern is gradual so it is difficult to conclude how it meshes with the projected change in the ENSO state. Of interest is the dryness shown for the Southwest in MJJ 2023 indicating a slow start to the Southwest Monsoon.

It is a bit surprising that the Southwest is not shown as wetter if next winter is projected to be an El Nino winter. I believe that NOAA is hedging its bets because we are not yet beyond the Spring Prediction Barrier (SBP). Thus the confidence in the El Nino forecast is still low but I do not believe that this is addressed in the NOAA discussion. |

Comparing the new outlook with the prior Outlook,

The maps that were released last month.

A good approach for doing this comparison is provided with the temperature discussion.

| In terms of comparisons, the downgrading of the Southwest Monsoon from stronger than normal to normal is significant but was hinted at last month. Now it is shown as a late start but it could be more disappointing than that. But the level of confidence in the forecast of the Southwest Monsoon is always low but may be extra low this year. |

NOAA Discussion

Maps tell a story but to really understand what is going you need to read the discussion. I combine the 30-day discussion with the long-term discussion and rearrange it a bit and add a few additional titles (where they are not all caps the titles are my additions). Readers may also wish to take a look at the article we published last week on the NOAA ENSO forecast. That can be accessed here.

I will use bold type to highlight some things that are especially important. My comments, if any, are enclosed in brackets [ ].

CURRENT ATMOSPHERIC AND OCEANIC CONDITIONS

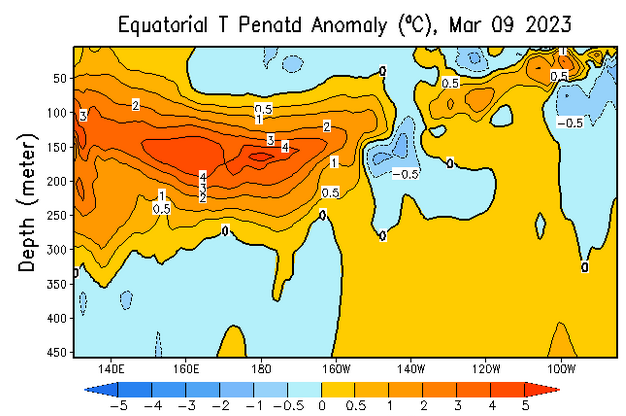

La Niña has ended and ENSO-neutral is now present in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Equatorial Pacific Ocean sea surface temperatures (SSTs) continued to warm over the past month with negative anomalies in SST only remaining in an area near and just east of the Date Line. The most recent weekly value of the Nino3.4 SST index is -0.1 degrees C. Further east toward the South American coast, positive anomalies in SST have developed with a region of greater than +0.5 degrees C departures in the eastern Pacific with the most recent value of the Niño1+2 SST index of +1.5 degrees C. Below the surface, the 0 – 300 meter depth equatorial temperature anomalies (i.e., integrated heat content) became positive in February 2023 and there exists a reservoir of warmer than normal water spanning a depth from approximately 75 m to 250 m from 130E to 150W with the maximum anomaly ranging from + 4-6 degrees C.

Although the oceanic indicators for La Niña have decreased in the Pacific Ocean, there does remain some atmospheric signature and it will likely take some time for this response to completely disappear. For example, in the past 30 day average, suppressed convection remained present near the Date Line along the equator and upper-level cyclonic circulations, symmetric about the equator in both hemispheres, are evident. Trade winds have decreased in magnitude, but this is in part due to a strong MJO event and associated westerly wind anomalies crossing the Pacific within the last month.

PROGNOSTIC DISCUSSION OF SST FORECASTS

Forecasts of the Nino3.4 SST index from the NMME are in general agreement for a transition from small negative anomalies to positive departures from normal of varying magnitudes ranging from +0.3 to +1.2 degrees C (for the GFDL SPEAR model) by late summer 2023. The NMME ensemble mean forecast enters El Nino territory (greater than +0.5 degrees C) approximately during July 2023.

The CPC Niño3.4 SST consolidation forecast follows a similar trajectory as the NMME models at the start, but hovers near or just below the +0.5 degrees C threshold during the late summer and early autumn months. Two statistical components of the CPC Nino3.4 SST consolidated forecast, the CA and CCA forecasts, predict a much more rapid transition towards El Niño with values of the Niño3.4 index near or surpassing +1.0 degrees C by autumn 2023.

The official CPC ENSO outlook favors ENSO-neutral through the JJA season with El Niño favored thereafter at an approximate 60% probability through OND 2023.

30-DAY OUTLOOK DISCUSSION FOR APRIL 2023

The La Niña event has ended as of March, 2023. Sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies have tended towards positive across most of the equatorial Pacific Ocean in recent weeks, and the most recent Niño 3.4 region anomaly is approaching zero degrees Celsius. The East Pacific is particularly warm with an anomaly of +1.5 C in the Niño 1+2 region. [Editor’s Note: I think the Emily Becker post on ENSO Blog is one place where the Coastal El Nino off the coast of Peru was discussed. HERE is the link] Easterly equatorial wind anomalies over the Pacific Ocean have weakened in the last month and are confined to a small area of the central Pacific. Upper-level westerly wind anomalies continued over the eastern equatorial Pacific. Positive subsurface temperature anomalies observed in the western and central equatorial Pacific Ocean have expanded eastward, while extending towards the surface in the eastern Pacific Ocean. Negative subsurface temperature anomalies near the surface of the central Pacific Ocean have weakened. Although ENSO-neutral conditions are predicted in the official ENSO outlook to continue through the Northern Hemisphere spring, a rapid warming of the Niño 3.4 region SST anomaly is forecast by most statistical and dynamical models , with an increasing chance of an El Niño from summer into autumn. Consolidated dynamical model forecasts from the North America Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) predict positive SST anomalies in the Niño 3.4 region, bordering on El Niño conditions near the 0.5 degree C threshold, from summer through autumn. The Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) strengthened significantly in the beginning of March with convective activity currently over the Western Hemisphere. Dynamical model forecasts of the Real-time Multivariate MJO (RMM) index indicate a weakening MJO signal propagating eastward into the Indian Ocean towards the end of March.

Temperature

The ECMWF dynamical model forecasts for the beginning of April indicate likely below-normal temperatures for much of the western contiguous U.S. (CONUS) and parts of the northern Great Plains. Anomalous snowpack and snow cover over parts of the West play a role in the temperature outlook for April. In addition to surface boundary conditions, near-coastal sea surface temperature anomalies were considered. Linear regression forecasts based on the RMM index indicate a potential for below-normal temperatures across much of the CONUS at the beginning of April, followed by warming, particularly in the East. The temperature and precipitation outlooks for April are based primarily on a skill-weighted consolidation of dynamical model forecasts from the North America Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME). Statistical tools, such as the Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA), Constructed Analog (CA), and a linear regression model based on the CPC SST Consolidation forecast of the Nino 3.4 index and decadal trends were considered, but played a lesser role given the uncertainty of ENSO-related signals given the rapid transition in the ENSO state. In addition, skill-based consolidations of statistical and dynamical tools for temperature and precipitation were consulted.

The April Monthly Outlook favors below-normal temperatures for southwestern Alaska, as indicated by the NMME consolidation tool, with negative SST anomalies along the coast contributing to cooler temperatures. Above-normal temperatures are favored for northeastern Alaska, supported by the NMME consolidation tool, as well as the statistical forecast tool consolidation. The probability of below-normal temperatures is enhanced in the Pacific Northwest, Northern Rockies, and parts of the Great Basin, supported by recent CFSv2 and ECMWF dynamical model forecasts for April, and consistent with areas of anomalous snow cover and deep snowpack. Negative SST anomalies near the Pacific coast contribute to an increased likelihood of below-normal temperatures for the coasts of California, Oregon and Washington. Above-normal temperatures are favored from parts of the Southwest eastward across the Southern Plains, and from the Gulf Coast region northward across the eastern CONUS, as indicated by the NMME model forecasts. Strong positive SST anomalies along the Gulf Coast increase the likelihood of above-normal temperatures. Conflicting signals in the temperature forecast tools lead to equal chances of below, near and above-normal temperatures in the April outlook over a large area of the north-central CONUS.

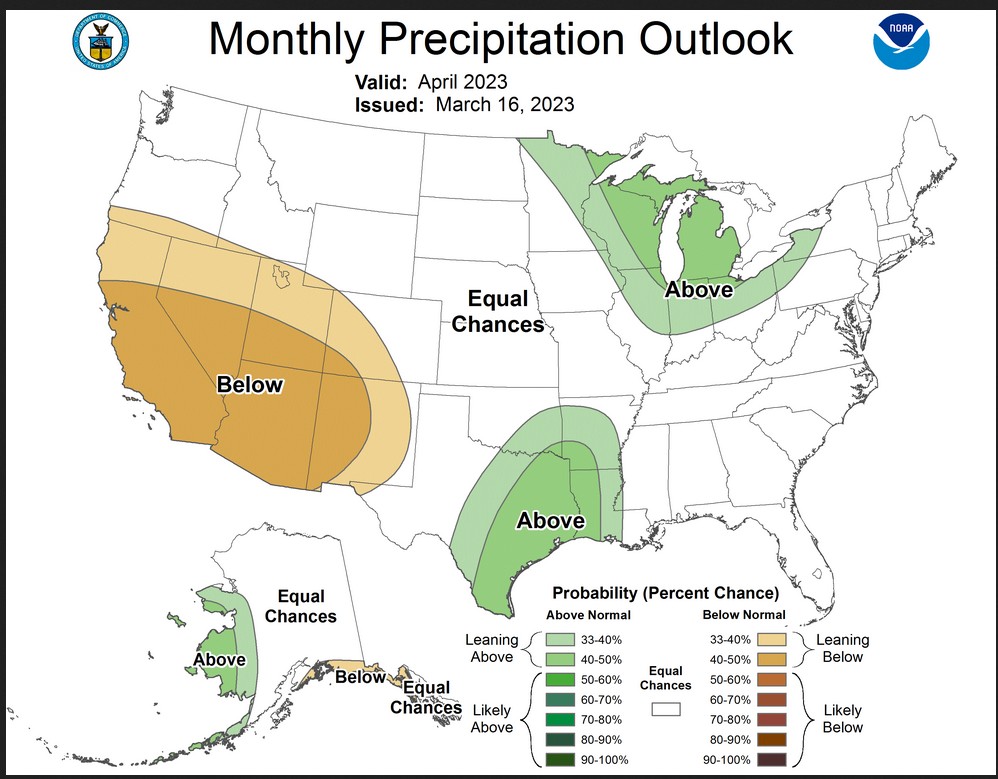

Precipitation

Above-normal precipitation is favored for parts of the west coast of Alaska, as indicated in the precipitation consolidation of dynamical and statistical tools and the CFSv2 model forecasts. Below-normal precipitation is slightly favored for parts of the south coast of Alaska, as predicted by the NMME precipitation anomaly forecast. Below-normal precipitation is favored for a large area of the western CONUS from California and southern Oregon to the Central and Southern Rockies, as predicted by most dynamical and statistical model forecasts and consistent with decadal precipitation trends for April. Above-normal precipitation is favored from the western Gulf Coast region northward into parts of Oklahoma and Arkansas, as predicted by the dynamical and statistical model forecast consolidation. Above-normal precipitation is also favored for parts of the Midwest and Great Lakes region, supported by recent dynamical model forecasts such as the CFSv2 and ECMWF, and consistent with decadal precipitation trends for April.

SUMMARY OF THE OUTLOOK FOR NON-TECHNICAL USERS (Focus on April – May – June)

In early March 2023, the final La Niña advisory was issued and La Niña has ended. ENSO-neutral is now present in the equatorial Pacific ocean and favored to continue through the spring and early summer months. Thereafter, El Niño is the most likely phase of ENSO from late summer into the autumn months.

Temperature

The April-May-June (AMJ) 2023 temperature outlook favors above-normal seasonal mean temperatures for the north slope of Alaska, parts of the Southwest, southern Plains and Southeast and northward to include the Ohio Valley, Mid-Atlantic and Northeast. Below-normal temperatures are most likely for portions of the Northern Plains and central interior West.

Precipitation

The AMJ 2023 precipitation outlook favors above-normal seasonal total precipitation amounts for portions of the Great Lakes, Ohio Valley, Mid-Atlantic and Northeast. Below-normal precipitation is most likely for parts of the far Pacific Northwest and Southwest.

Equal chances (EC) are indicated for areas where seasonal mean temperatures and seasonal total precipitation amounts are favored to be similar to climatological probabilities.

BASIS AND SUMMARY OF THE CURRENT LONG-LEAD OUTLOOKS

PROGNOSTIC TOOLS USED FOR U.S. TEMPERATURE AND PRECIPITATION OUTLOOKS

Given some likely remaining La Niña atmospheric response at times during April 2023, typical La Niña impacts are considered to a minor degree very early in this set of outlooks (i.e., AMJ 2023). Current anomalous soil moisture and snow cover/depth are considered and contributed strongly to the outlook in some locations during the AMJ and MJJ seasons.

Dynamical model forecasts from the NMME and C3S multi-model ensemble systems are utilized heavily, although precipitation signals are particularly weak from this month’s guidance as compared to normal. Moreover, the Calibration, Bridging and Merging (CBaM) tool anchored to the NMME forecasts and “bridged” to the Niño3.4 index is also significantly utilized. The ENSO-OCN forecast tool that targets impacts from ENSO, as predicted by the CPC consolidation SST forecast, and long term trends played a large role in many of the outlooks,especially at longer leads.

Consideration and some slight adjustments consistent with potential development of El Niño are done in some areas beginning in late summer and autumn 2023, but any changes are minor at this stage given the uncertainty in the ENSO forecast initialized during this time of the seasonal cycle (i.e., spring predictability barrier).

PROGNOSTIC DISCUSSION OF OUTLOOKS – AMJ 2023 TO AMJ 2024

TEMPERATURE

The AMJ 2023 temperature outlook favors above-normal seasonal mean temperatures from the Southwest eastward to the southern Plains and Southeast as well as northward to include the Ohio Valley, mid-Atlantic and Northeast. The greatest odds of above-normal temperatures is for Texas and areas along the Gulf coast and Eastern Seaboard. There is strong support for warmer than normal temperatures in this region from nearly all dynamical model guidance and statistical forecast tools as well as long term positive temperature trends. Very dry soil moisture conditions and well as above-normal local coastal SSTs, further enhance these odds for the southern High Plains and Gulf / Atlantic coasts respectively.

Elevated odds of below-normal temperatures are forecast for the Northern Plains where abnormally deep snowpack is in place and long term negative temperature trends exist. Dynamical model forecast guidance from some participant models of the NMME and C3S suite as well as the CBaM hybrid forecast tool support this forecast.

A small region of favored below-normal temperatures is highlighted for an area in the interior western CONUS. Odds tilting toward below-normal temperatures in this area, however, are very modest. The AMJ and MJJ 2023 temperature outlook for the western U.S. is challenging due to considerably above normal snowpack and soil moisture as a result of recent storminess in February and March, offset by forecasts of warmer than normal temperatures predicted by some dynamical and statistical forecast guidance. Forecasts from some of the statistical forecast tools and dynamical models indicate high odds for above-normal temperatures in the western CONUS from lead 1 onward – perhaps linked to a more rapid transition to warmer than average equatorial Pacific SSTs and potential consequent atmospheric response. The higher odds for above-normal temperatures from these tools seems overdone at the start of this month’s set of outlooks given the highly anomalous snowpack and soil moisture conditions at the start of AMJ 2023.

Although the impact of enhanced surface wetness (either soil moisture to start or melting snowpack and consequent elevated soil moisture) is likely to diminish relatively quickly as the month of May progresses and in June, the season as a whole may still tilt slightly toward below-normal temperatures. The monthly temperature outlook for April 2023 favors below-normal temperatures for considerable areas in the western U.S. Equal-chances (EC) is forecast for much of the remaining area in the western CONUS due to these competing influences. There is also support for areas of favored below-normal temperatures in the western CONUS from the ECMWF model guidance, the CA forecast tool based on soil moisture, and the CBaM hybrid tool.

Negative trends in sea ice coverage and thickness and so more open water earlier than normal for ocean areas along the northwest and northern coast of Alaska favors above-normal temperatures for these areas during AMJ 2023. Elevated odds for below-normal temperatures remains for portions of the northern Plains during MJJ 2023, while favored above-normal temperatures increase in coverage and probabilities across the western CONUS from MJJ through ASO 2023. Weaker and conflicting signals in the forecast tools increase uncertainty for the north-central U.S. and so the area forecast as EC increases from the JJA through OND 2023 seasons.

Primarily beginning in SON 2023, the remaining outlooks are largely based on the ENSO-OCN forecast tool which is heavily influenced by long-term trends at these leads with some slight adjustments, at this stage, for the potential influence of El Niño. For Alaska, increased forecast coverage of favored above-normal temperatures is depicted from MJJ through SON 2023.

PRECIPITATION

The AMJ 2023 precipitation outlook favors above-normal seasonal total precipitation amounts for portions of the Great Lakes, Ohio Valley, Mid-Atlantic and Northeast based on long term positive precipitation trends as defined by OCN, dynamical model guidance from some participant models from the NMME and C3S ensemble systems, the CA forecast tool based on anomalous soil moisture and potential residual La Niña impacts.

Below-normal precipitation is favored for parts of the far Pacific Northwest and the Southwest U.S. where some dynamical model forecast guidance, the CBaM hybrid tool, the ENSO-OCN forecast tool and long term negative precipitation trends supported the outlook.

It is important to note that signals from the dynamical model suite for precipitation are especially weak for basically all forecast leads for which forecast guidance is available, even when considering shoulder seasons within the seasonal cycle as well as the transition to ENSO-neutral.

Favored above-normal precipitation in the eastern CONUS is forecast to shift eastward and southward with time from MJJ through JJA and then transition westward by ASO 2023. This evolution is based on long term positive precipitation trends and to a lesser degree signals from the NMME and C3S model guidance.

Favored below-normal precipitation forecast for the Pacific Northwest shifts to include parts of the northern Rockies from MJJ through JAS 2023 – a result of the ENSO-OCN forecast tool, long term negative precipitation trends and some dynamical model forecast support. For the Southwest, below-normal precipitation is most likely to continue during MJJ 2023, albeit with smaller forecast coverage.

Unlike 2022, there are less climate signals to utilize for prediction of the first half of the Southwest summer monsoon. Enhanced wetness across the western CONUS from an extremely wet winter may lead to a potentially delayed start and less robust monsoon circulation due to perhaps less efficient heating of the land and so a weaker thermodynamic induced circulation. The CBaM hybrid forecast tool, does favor below-normal precipitation in the Southwest during the monsoon season, but there remains considerable uncertainty given the evolution of ENSO and how that may or may not influence precipitation in the region this summer.

Climate signals for the state of Alaska for AMJ 2023 are quite weak and conflicting amongst the tools when present, so EC is forecast for the entire state. However, above-normal precipitation is most likely for parts of northern and central Alaska beginning in MJJ 2023 and continuing through the remainder of 2023. Model guidance and more open water earlier in the seasonal cycle are the basis for these highlighted areas.

Primarily long term precipitation trends and slight tilts in deference to potential EL Niño development are used in making the remainder of the precipitation outlooks through AMJ 2024.

Review of the ENSO Assumptions utilized by NOAA (CPC) in Preparing this Four-Season Outlook

It is useful to review the ENSO forecasts used by NOAA to produce this Four-Season Outlook. We reported on that last week and you can read that article by clicking HERE

The key information used by NOAA follows.

IRI CPC ENSO STATE Probability Distribution (IRI stands for the International Research Institute for Climate and Society)

Here are the new forecast probabilities. This information is released twice a month and the first release is based on a survey of Meteorologists, the second is based on model results. The probabilities are for three-month periods e.g. FMA stands for February/March/April. I am just showing the first release which is what we have and presumably what NOAA (actually their CPC Division) worked from.

| It is early but the probabilities shown for JJA 2023 and beyond are very interesting. Are we headed for El Nino? It appears so but is still too early to be certain about that. In another month perhaps we will be a lot more certain. |

Tropical Subsurface Temperature Anomalies

| You can update this graphic by clicking HERE and scrolling down to “Mean and anomalous equatorial temperatures“. You can see the anomalously warm water at depth partially undercutting the anomalously cool water. Also, notice the warm tongue extending on the surface from the east. It is subtle but less subtle than last month. We have left La Nina in terms of ocean conditions. |

| The image will update if you click HERE. https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/people/wwang/cfsv2fcst/images3/nino34SeaadjPDFSPRDC.gif It is pretty bullish about an El Nino arriving pretty soon. |

Resources

The link for the drought outlook map and some discussions that come with the map can be found by clicking HERE.

| I hope you found this article useful and interesting. |