The full data sets for the 71 years from 1952 to 2022 show no discernable association patterns (correlations) for financial sector debt growth and inflation changes.1 This post continues that analysis by looking specifically at the various regimes of inflation change during the 71-year timeline.

From an image by Qubes Pictures from Pixabay

Introduction

The 71 years from 1952 to 2022 are divided into three types of inflationary behavior:1

- Significant inflation increases;

- Significant inflation decreases;

- No significant inflation changes.

An inflation change is significant if it is ≥4.0% with no intervening countertrend change >1.5%.

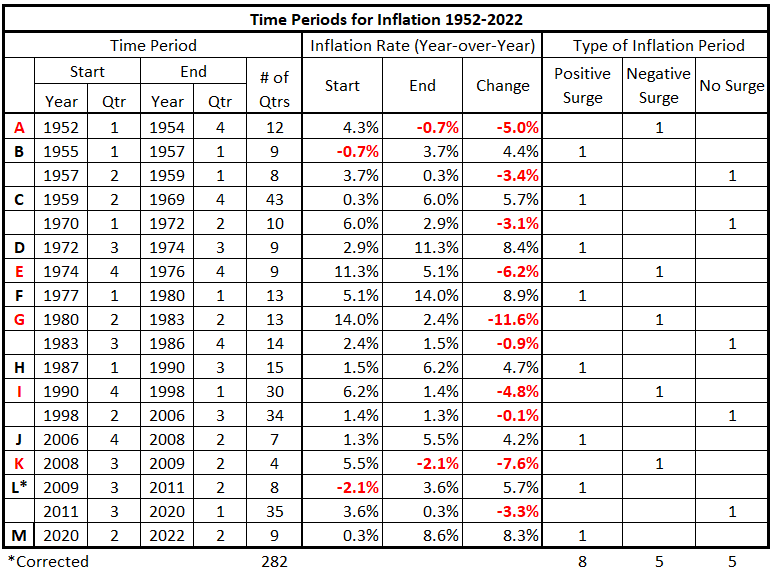

Previously, we defined the partitioning of inflation into the pattern in Table 1.

Table 1. Timeline of Inflation Data 1952-2022 (Previously Table 4*.2)

We will examine each category of inflation behavior separately. In this piece, we analyze the significantly positive periods of inflation (positive inflation surges).

Data

The data is from Tables 5-17, prepared previously.1

There are 13 quarterly timeline alignments:

- Financial Sector Debt and CPI Inflation quarters are coincident.

- Financial Sector Debt leads and lags CPI Inflation by one quarter (±3 months)

- Financial Sector Debt leads and lags CPI Inflation by two quarters (±6 months)

- Financial Sector Debt leads and lags CPI Inflation by three quarters (±9 months)

- Financial Sector Debt leads and lags CPI Inflation by four quarters (±12 months)

- Financial Sector Debt leads and lags CPI Inflation by six quarters (±18 months)

- Financial Sector Debt leads and lags CPI Inflation by eight quarters (±24 months)

Analysis

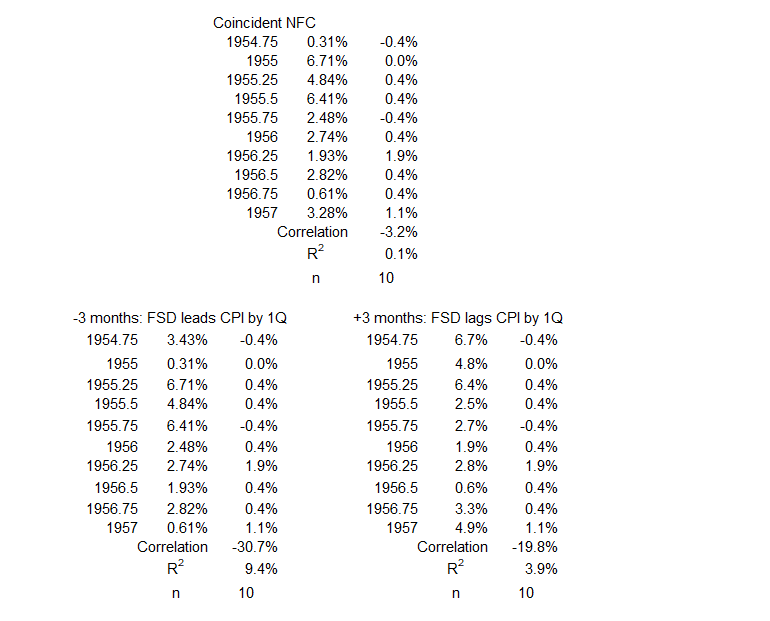

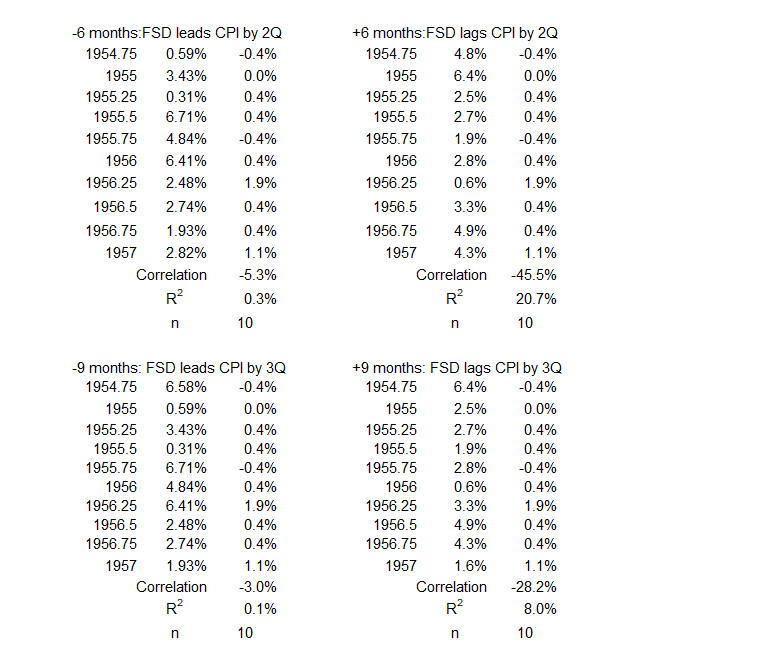

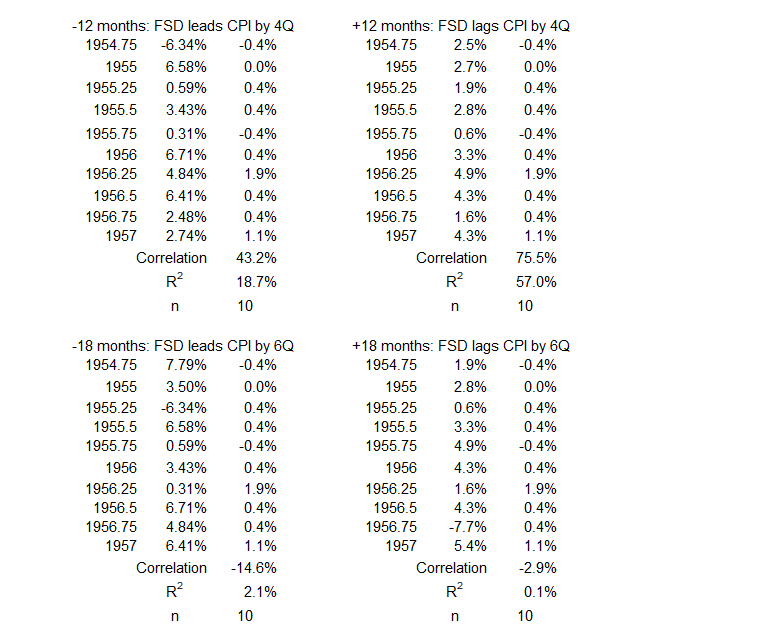

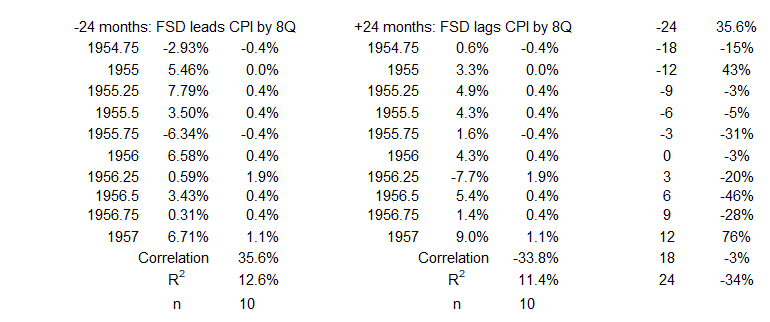

1Q 1955 – 1Q 1957

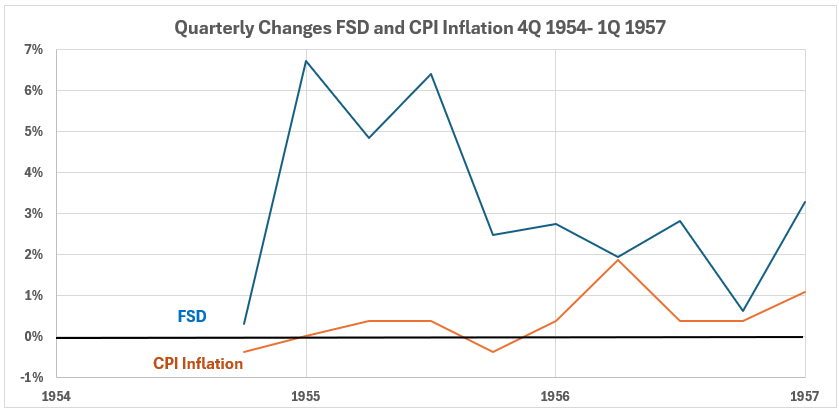

Figure 1. Financial Sector Debt Growth and Inflation 1Q 1955 – 1Q 1957

The general observations for this data are:

- Inflation trends upward.

- After an initial rise in 4Q 1959, FSD trends downward.

- There is a peak in inflation in 956 nine and fifteen months after peaks in FSD.

- The quarterly changes for inflation are smaller than for FSD.

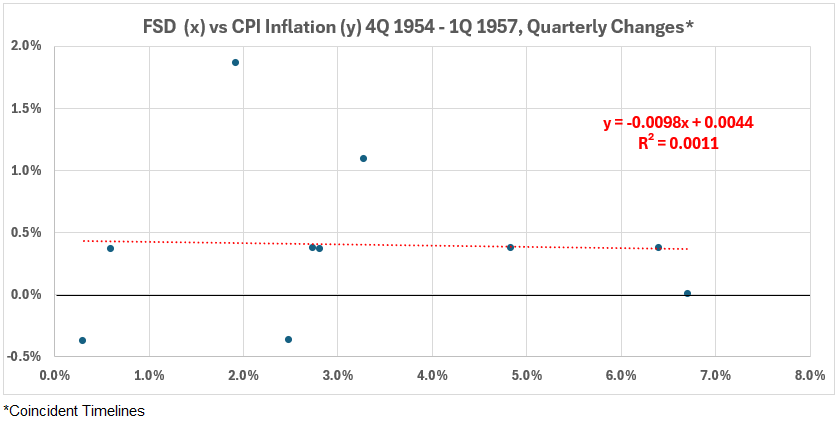

Figure 2. Quarterly Changes in Financial Sector Debt (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 1Q 1955 – 1Q 1957

The association (correlation) between financial sectors debt changes and CPI Inflation is very weakly negative for this inflation surge period. R = –3.2%%, R2 = o.1%.

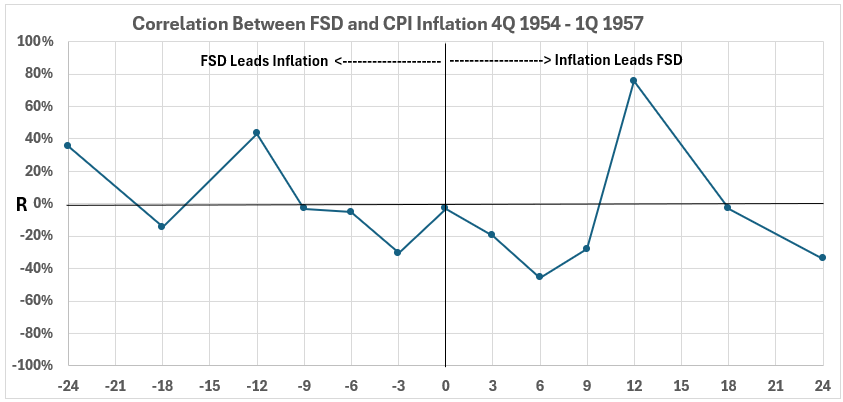

Figure 3. Correlation Between Financial Sector Debt and CPI Inflation 1Q 1955 – 1Q 1957

There are two weak associations between FSD and CPI Inflation when debt proceeds inflation by 12 and 24 months. R = 43% and 36%, respectively. R2 = 19% and 13%, respectively. All the other associations for debt changes preceding inflation are very weak or negligible. All associations for inflation preceding debt changes are negative except for one. The association is strongly positive when inflation precedes debt change by 12 months. R = 76%, R2 = 58%. All other associations on the right side of Figure 3 are weak, very weak, or negligible — and negative.

The data for CPI leading financial systems debt changes in time (right-hand side of the graph) indicates that rising CPI might possibly cause increased debt growth. A mitigating factor against this possibility is that the one timeline offset produces an association much different from all the others. This could be because that one strong correlation is coincidental and does not indicate possible causation.

2Q 1959 – 4Q 1969

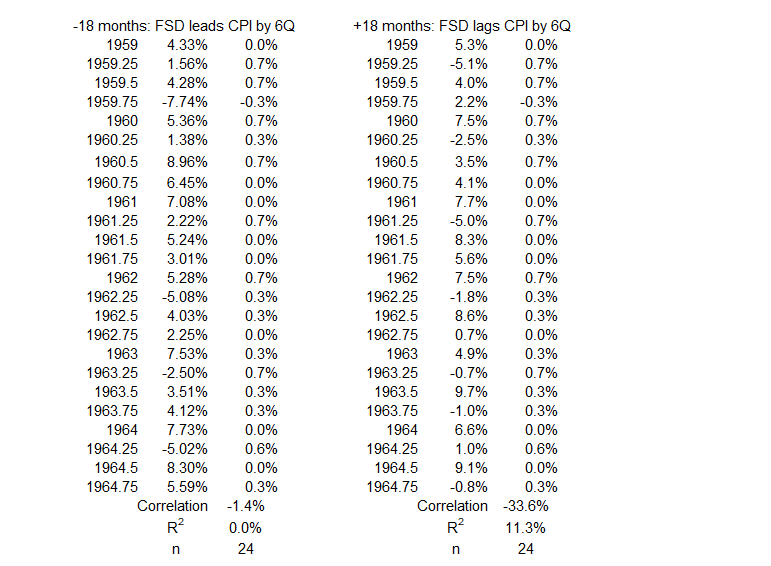

By our definition, the period from 1959 to 1969 constitutes a period of inflation growth—inflation growing by 4% or more without a pullback greater than 1.5%. However, the decade can be divided into slower inflation growth (1959-1964) and more rapid growth (1965-1969). Therefore, we analyzed the association between nonfinancial corporate credit and inflation in these periods.

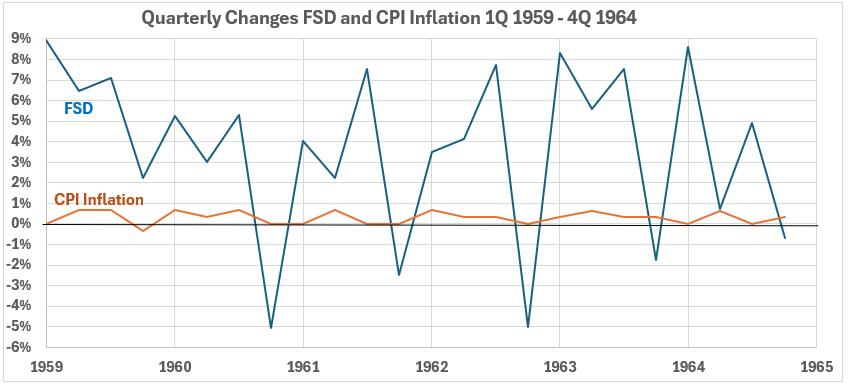

Figure 4. Financial Sector Debt and Inflation 1Q 1959 – 4Q 1964

The trends for quarterly changes in FSD, and especially inflation, were flat during this period. As seen previously, the volatility for FSD changes in much greater than for inflation.

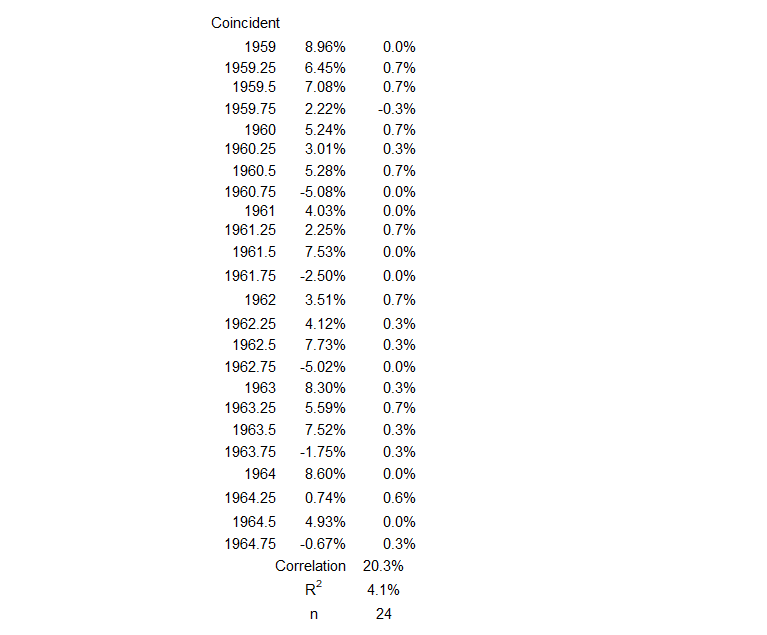

Figure 5. Quarterly Changes in Financial Sector Debt (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 1Q 1959 – 4Q 1964

This scatter diagram shows a very weak association for the coincident timeline data. R = 20%, R2 = 4.3%.

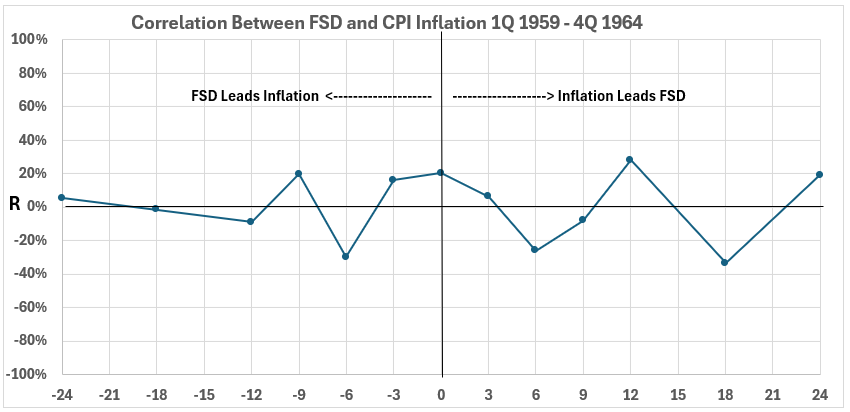

Figure 6. Correlation Between Financial Sector Debt and CPI Inflation 1Q 1959 – 4Q 1964

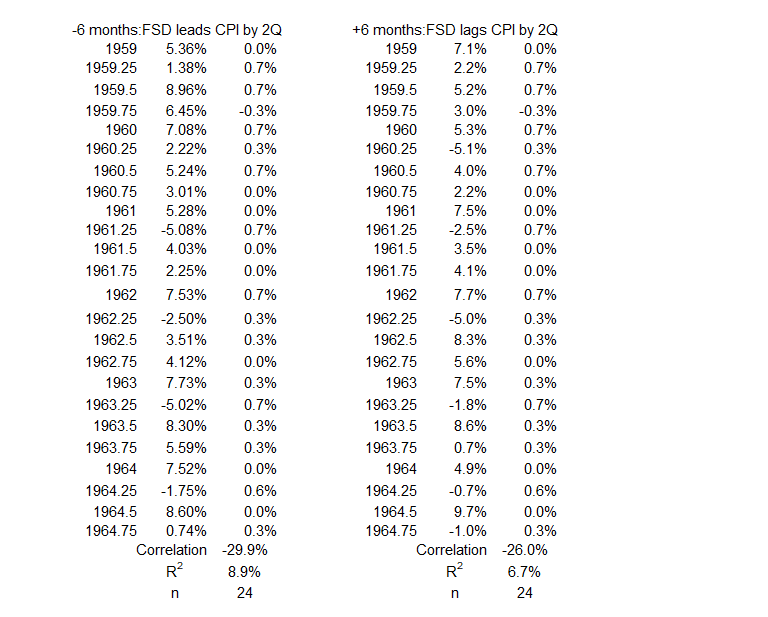

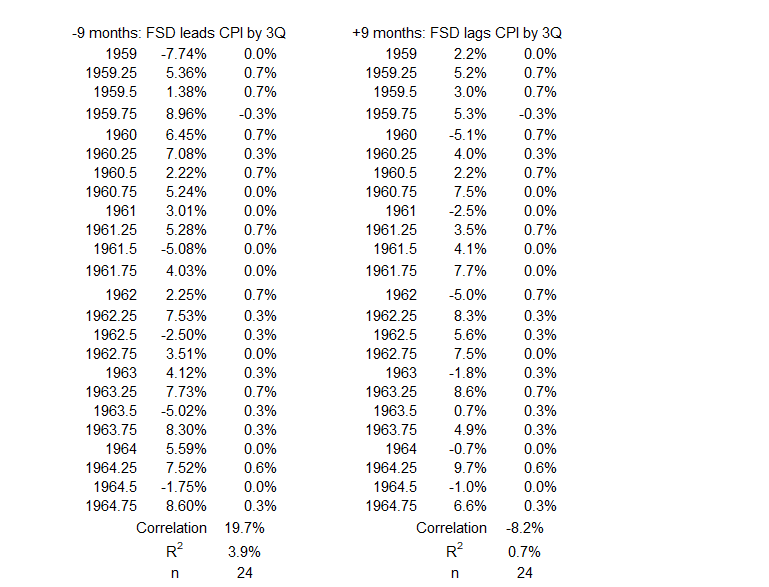

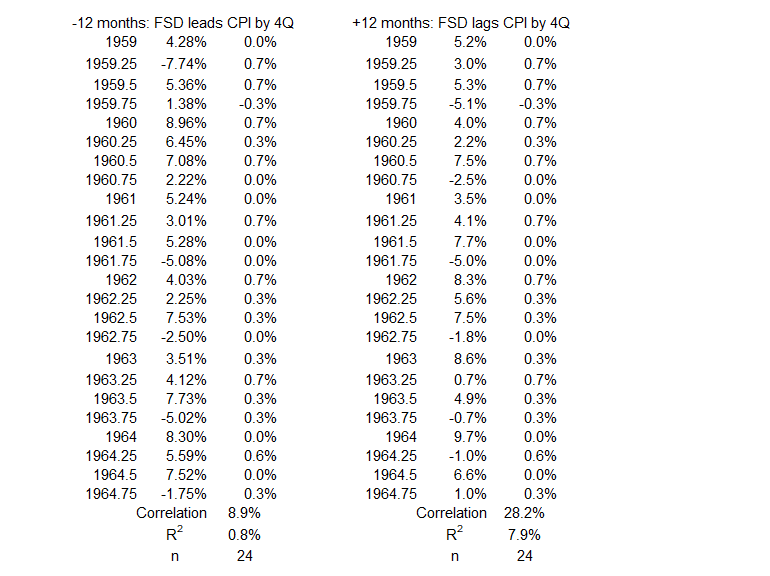

There was a very weak association between the two variables during this period, with four data pairs showing negligible correlation, R < 10%.

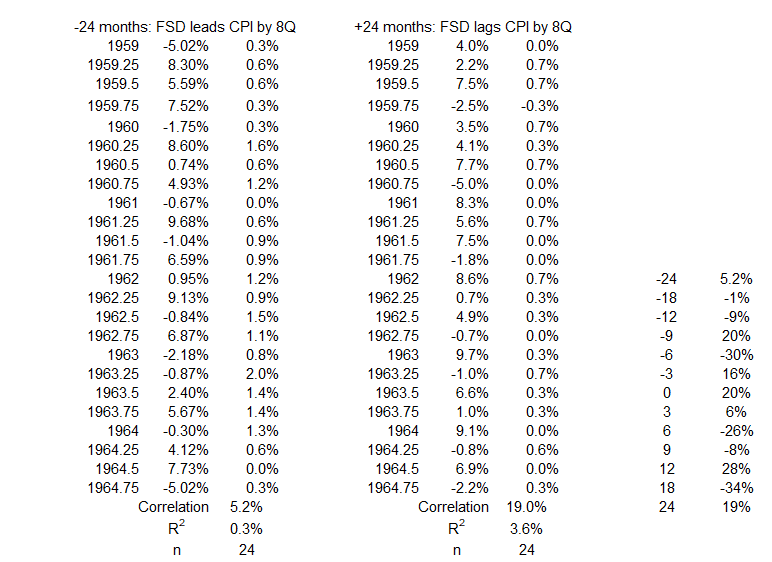

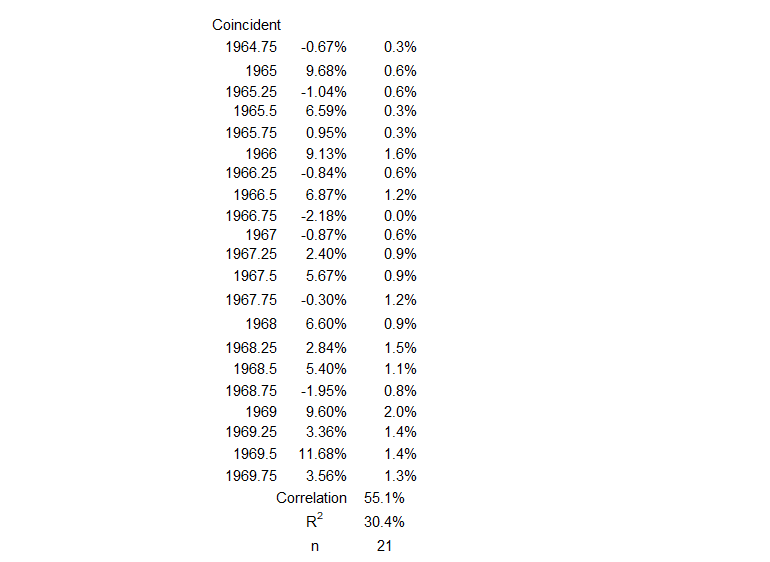

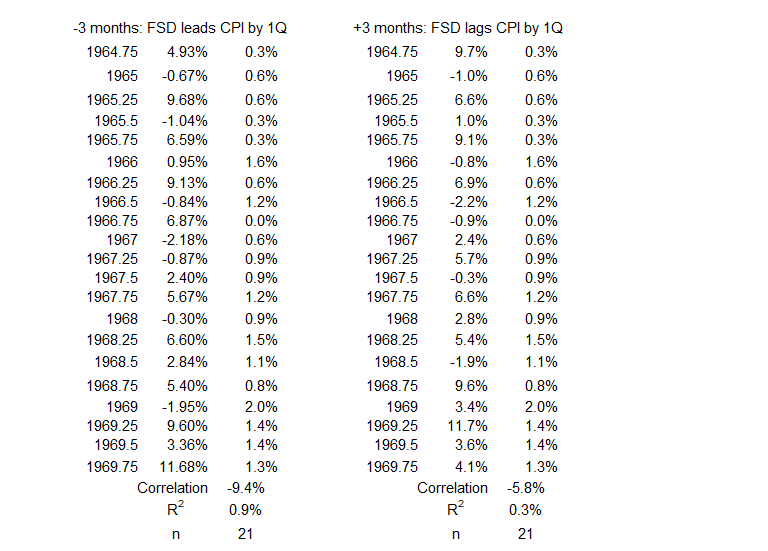

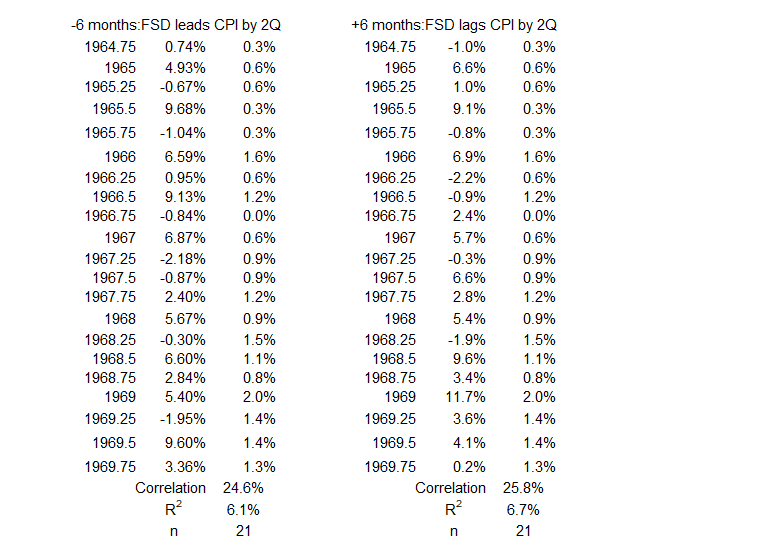

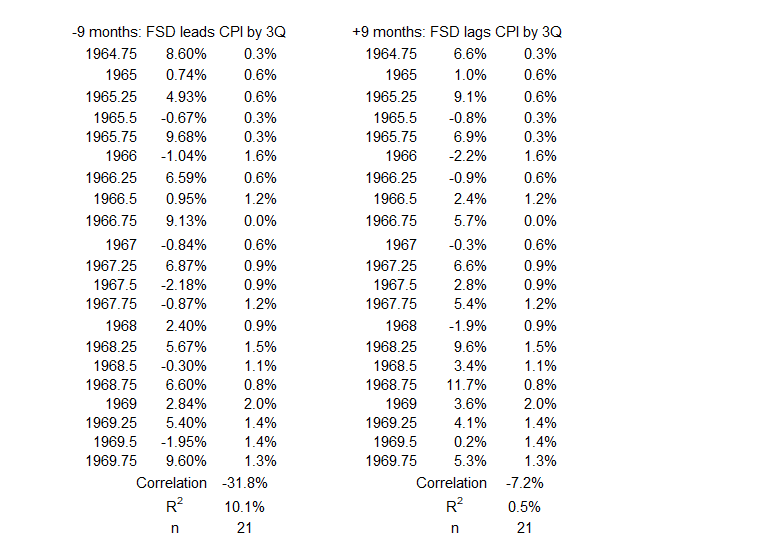

1Q 1965 – 4Q 1969

Figure 7. Financial Sector Debt Growth and Inflation 1Q 1965 – 4Q 1969

There are only two things to point out here. First, inflation has a general uptrend here, with more persistence after 1966. Secondly, the debt growth trend was flat here until there was an increase after the fourth quarter of 1968.

Figure 8. Quarterly Changes in Financial Sector Debt (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 1Q 1965 – 4Q 1969

The coincident timeline data has a moderate positive association, R = 55%, R2 = 30%.

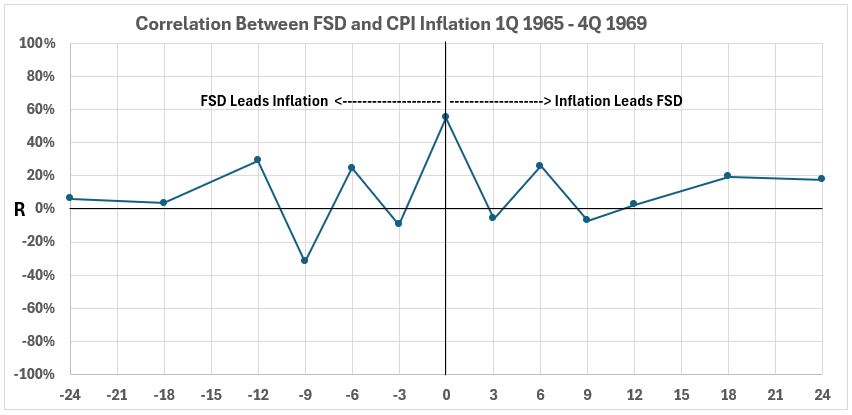

Figure 9. Correlation Between Financial Sector Debt and CPI Inflation 1Q 1965 – 4Q 1969

There is a weak or negligible association between the two variables during this period, except for inflation coinciding with debt change. (See Figure 8.) Because no lead/lag effects exist, it is not likely that there were any cause-and-effect relationships between nonfinancial corporate credit changes and inflation during this period.

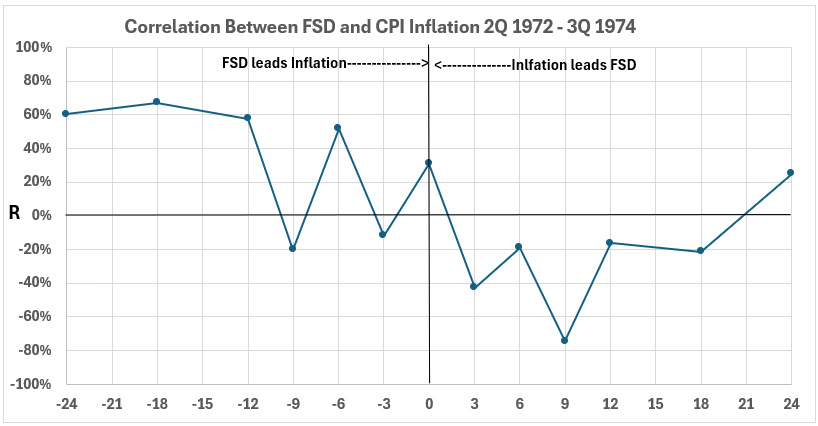

3Q 1972 – 3Q 1974

Figure 10. Financial Sector Debt and Inflation 2Q 1972 – 3Q 1974

Financial sectors debt had a nearly flat trend during this period, although still more volatile than changes in inflation. CPI Inflation changes are trending up for the entire time period.

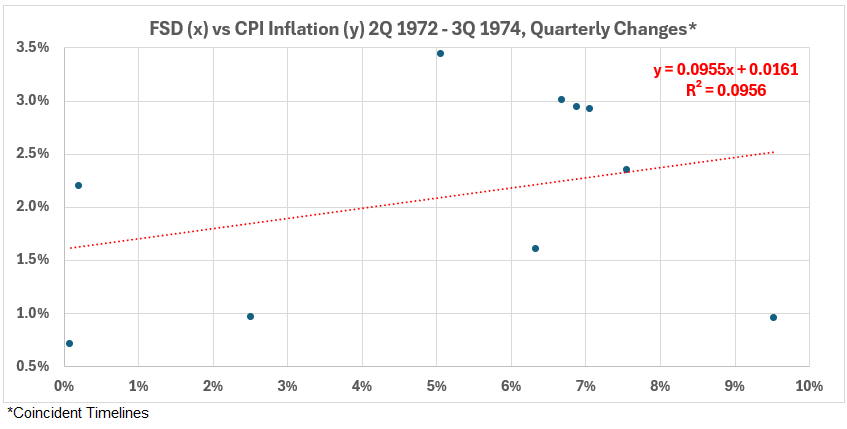

Figure 11. Quarterly Changes in Financial Sector Debt (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 2Q 1972 – 3Q 1974

The coincident timelines data shows a weak positive association (R = 30% and R2 = 10%).

Figure 12. Correlation Between Financial Sector Debt and CPI Inflation 2Q 1972 – 3Q 1974

There are moderate associations (correlations) when nonfinancial corporate credit changes preceded CPI Inflation by 6, 12, 18, and 24 months. These results indicate that FSD growth might have contributed to rising inflation here. (67% > R > 52%)

There is a strong negative association for inflation leading credit by nine months, R = –75% and R2 = 56%. The other data points on the right side of Figure 12 are all negative, except for the 24-month number. This leaves room for the possibility that increasing inflation might have led to a decrease in the growth of financial sector debt.

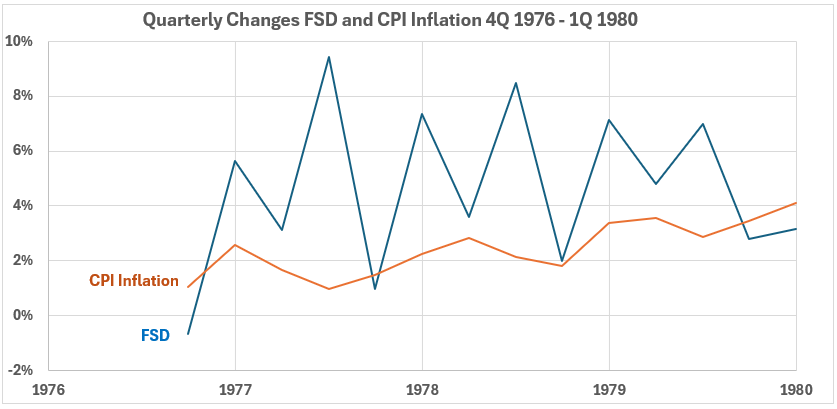

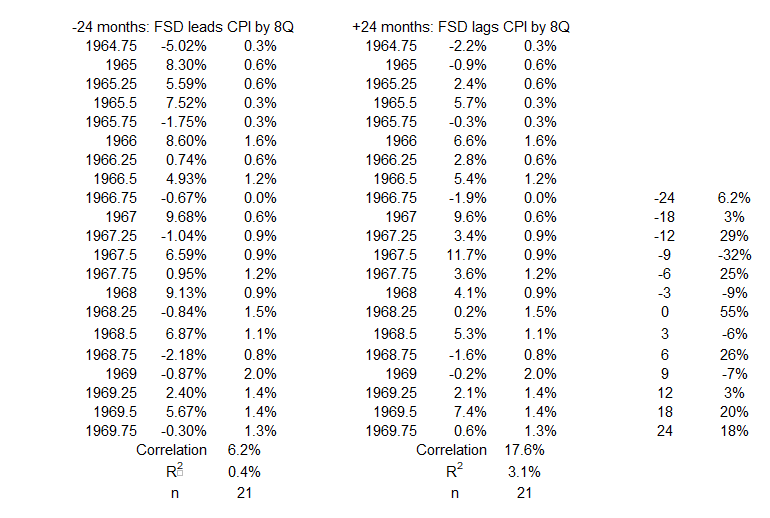

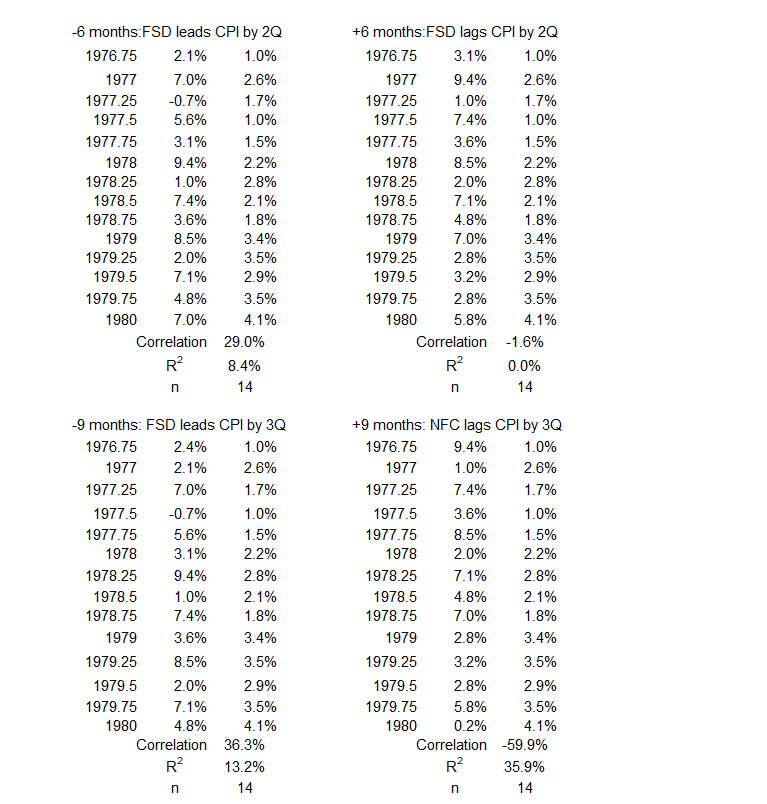

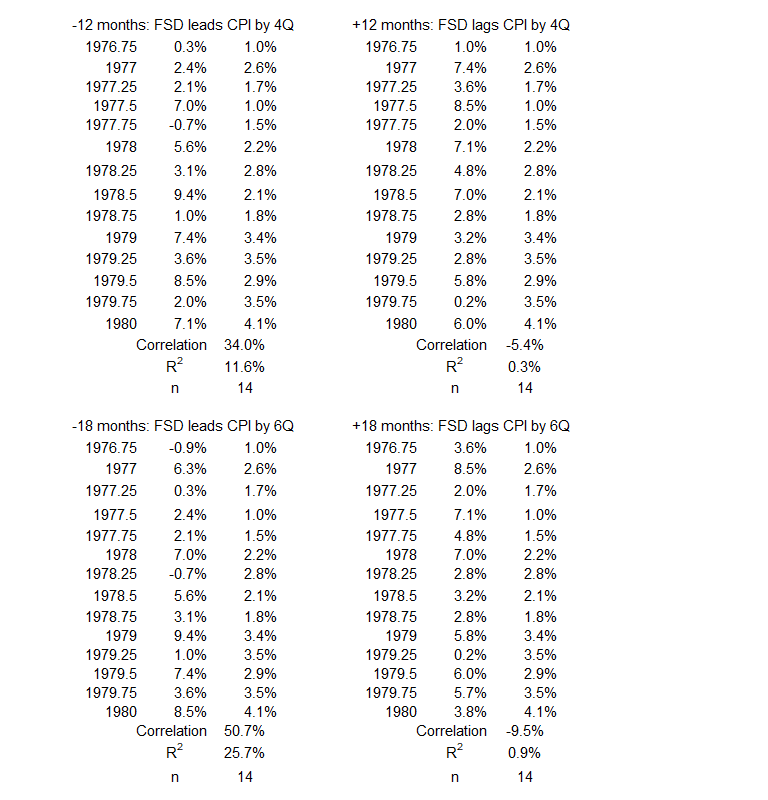

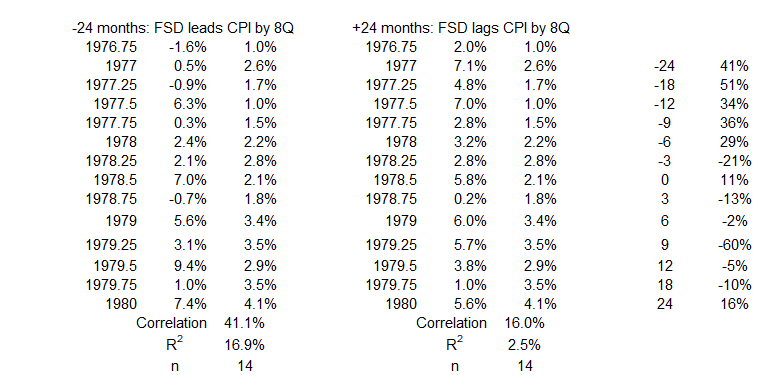

1Q 1977 – 1Q 1980

Figure 13. Financial Sector Debt and Inflation 4Q 1976 – 1Q 1980

Figure 13 shows financial sectors debt changes in a flat trend. CPI Inflation changes are in an uptrend.

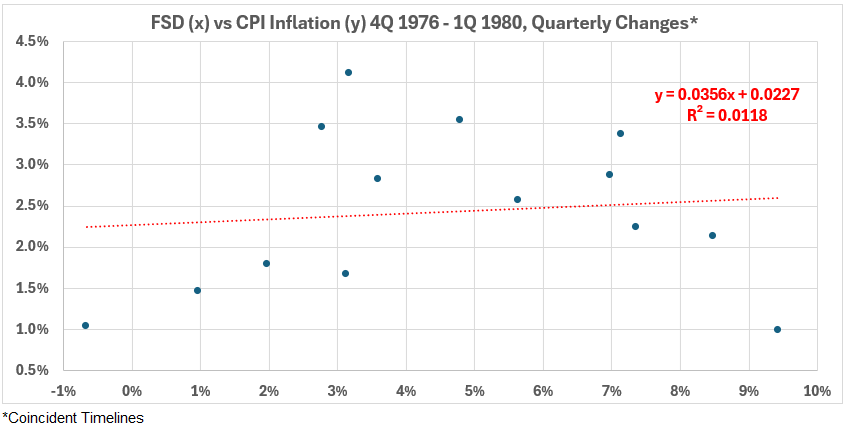

Figure 14. Quarterly Changes in Financial Sector Debt (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 4Q 1976 – 1Q 1980

The association between the two variables with coincident timelines is very weakly positive. R = 10.8% and R2 = 1.2%.

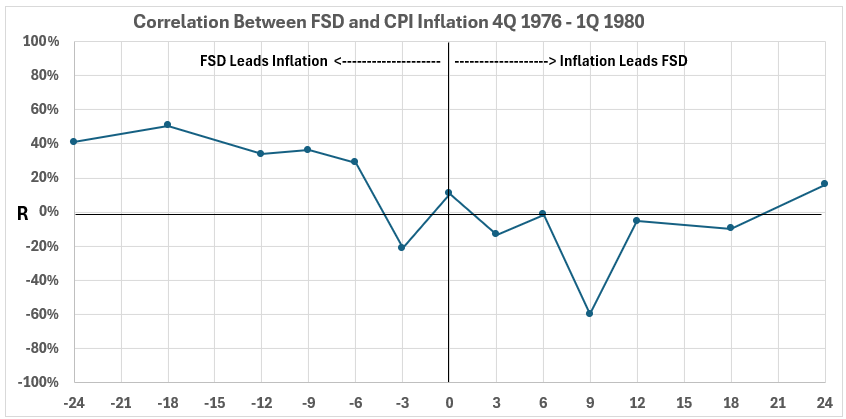

Figure 15. Correlation Between Nonfinancial Corporate Credit and CPI Inflation 4Q 1976 – 1Q 1980

Figure 15 is similar to Figure 12, with two exceptions. The first difference is that left-side associations (correlations) are weak from FSD lead times of six months or longer, except for a moderate association at 18 months. This suggests a lower possibility of FSD increases causing inflation in this period.

The second difference is that the negative association when inflation occurs before the debt changes also suggests less likelihood that inflation changes could affect credit.

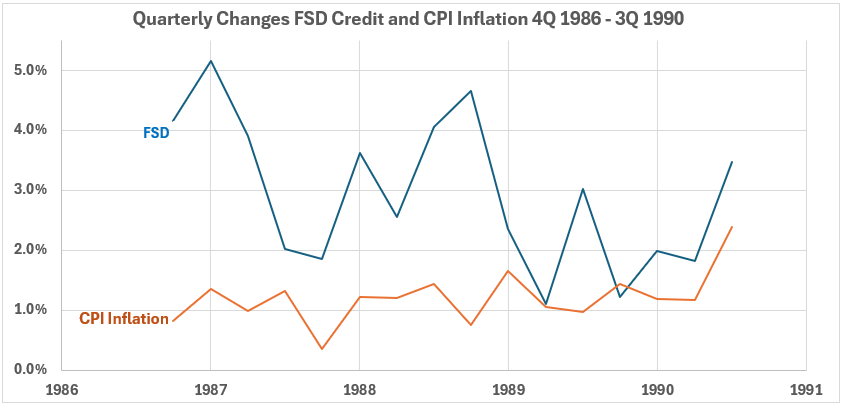

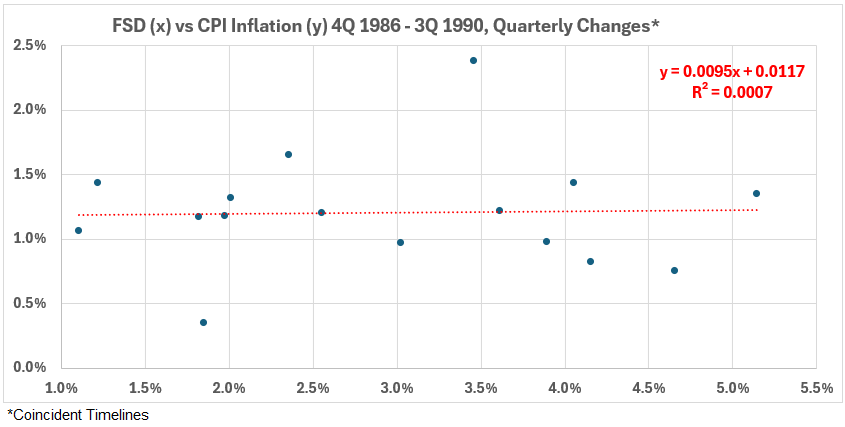

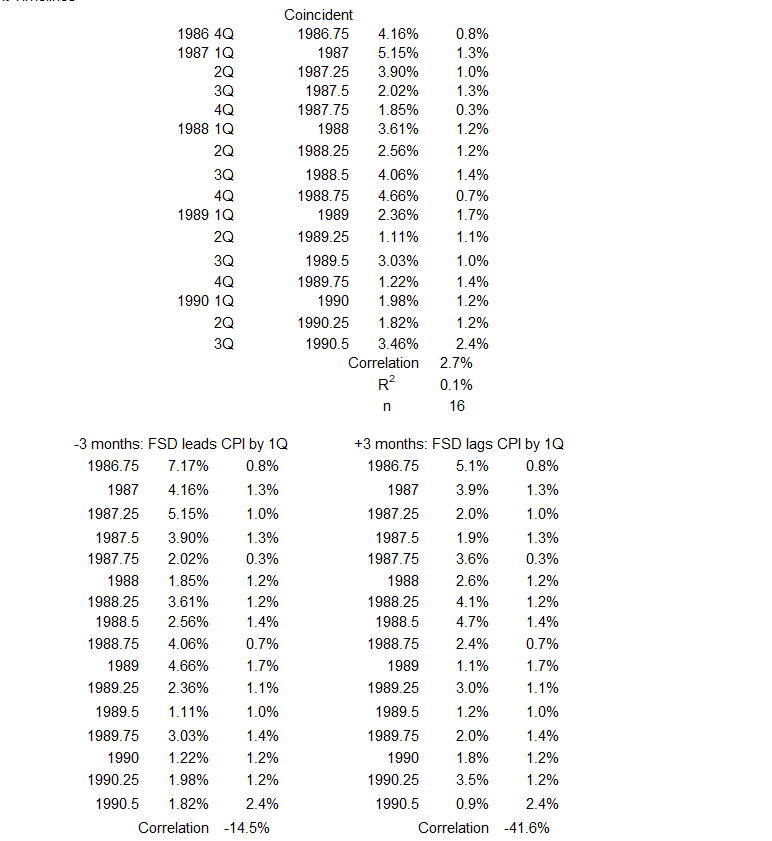

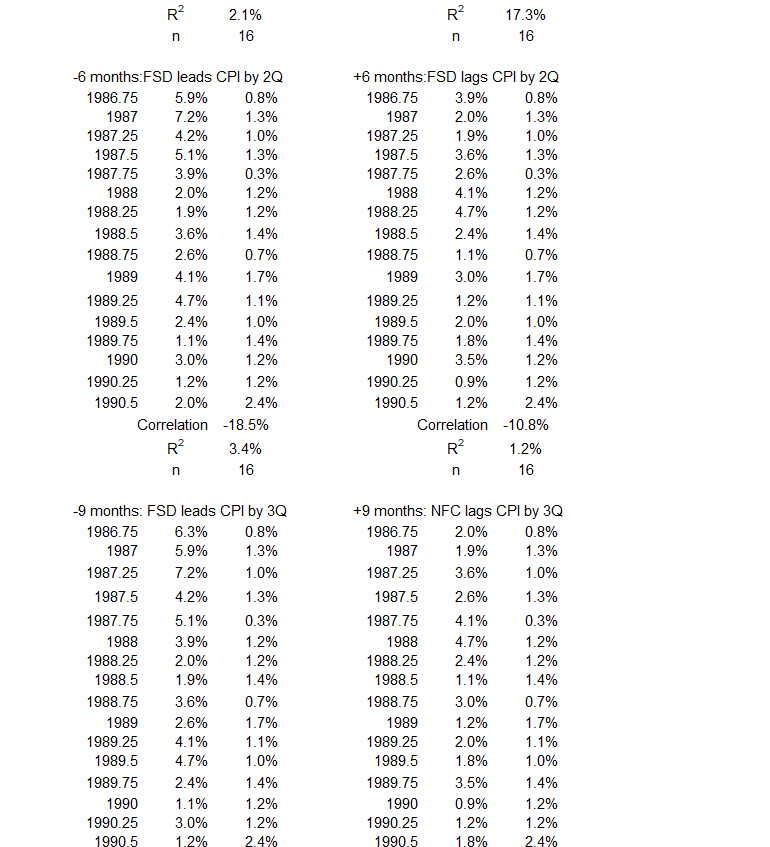

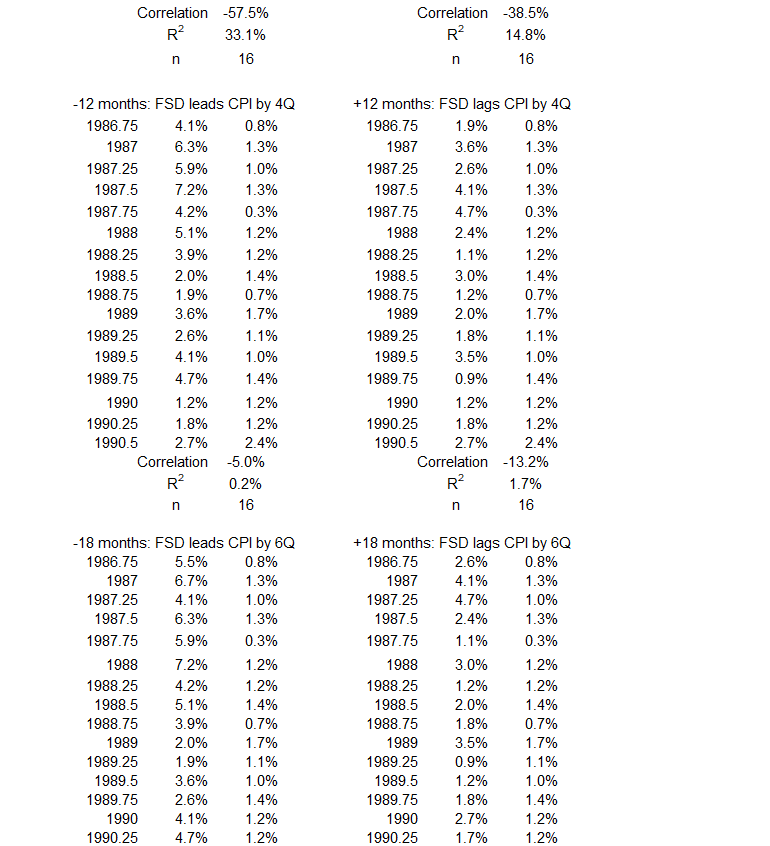

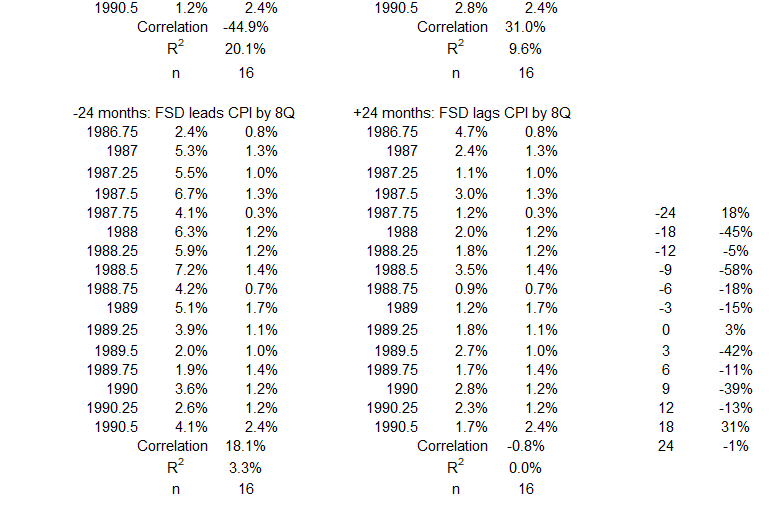

1Q 1987 – 3Q 1990

Figure 16. Financial Sector Debt and Inflation 4Q 1986 – 3Q 1990

This shows gradual up-trending changes in CPI Inflation while nonfinancial corporate credit changes are in a downtrend with a spike in the fourth quarter of 1988.

Figure 17. Quarterly Changes in Financial Sector Debt (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 4Q 1986 – 3Q 1990

Figure 17 data set shows a negligible positive association between the coincident timeline data sets, R = 2.7% and R2 = 0.1%.

Figure 18. Correlation Between Financial Sector Debt and CPI Inflation 4Q 1986 – 3Q 1990

This correlation diagram is not remarkable. The strongest associations are negative. They are all weak, except for debt leading inflation by nine months (R2 = 34%). This does not offer much opportunity for appreciable cause-and-effect relationships.

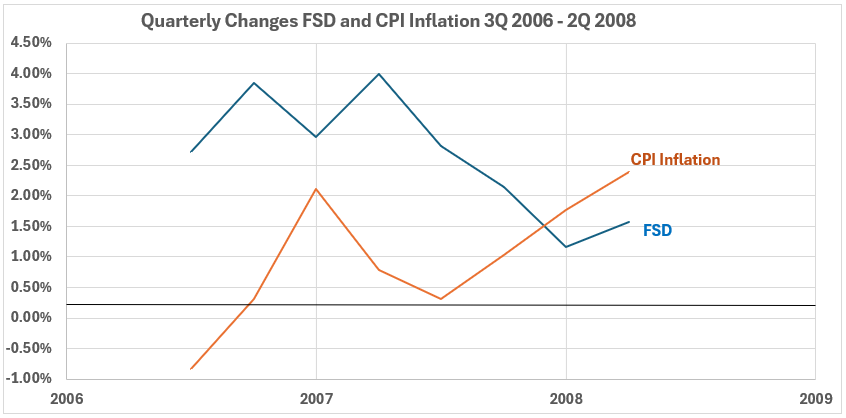

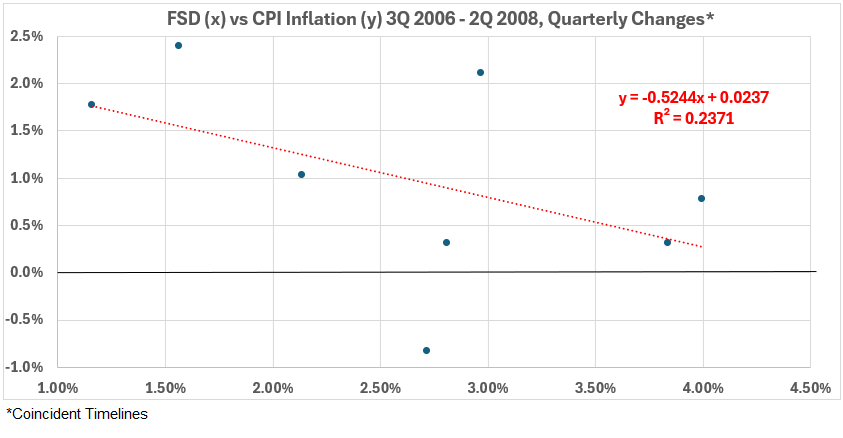

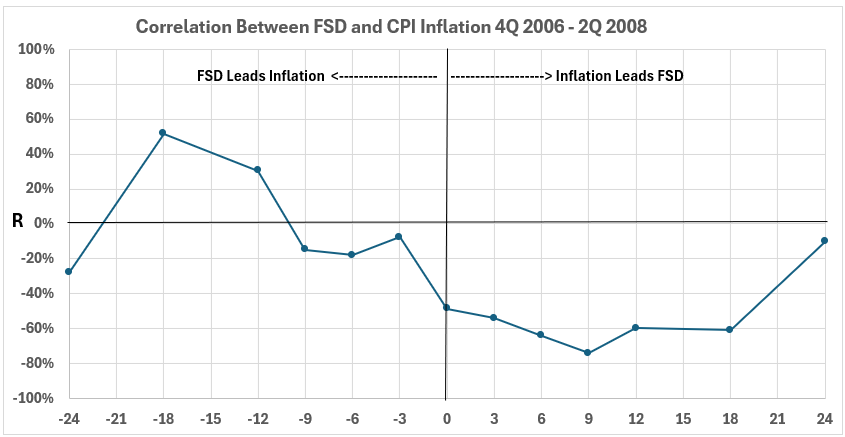

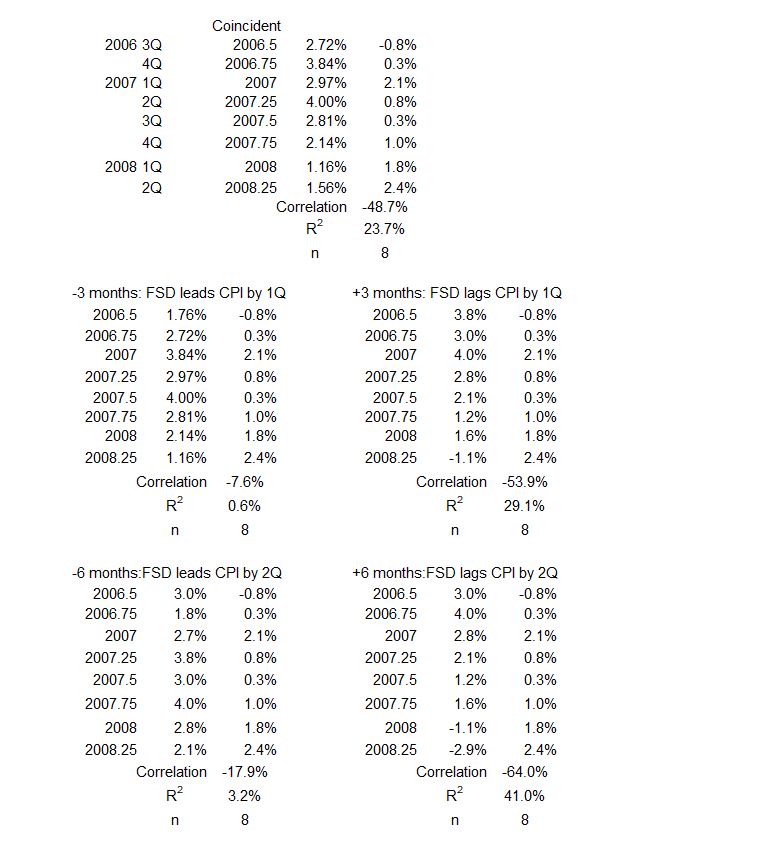

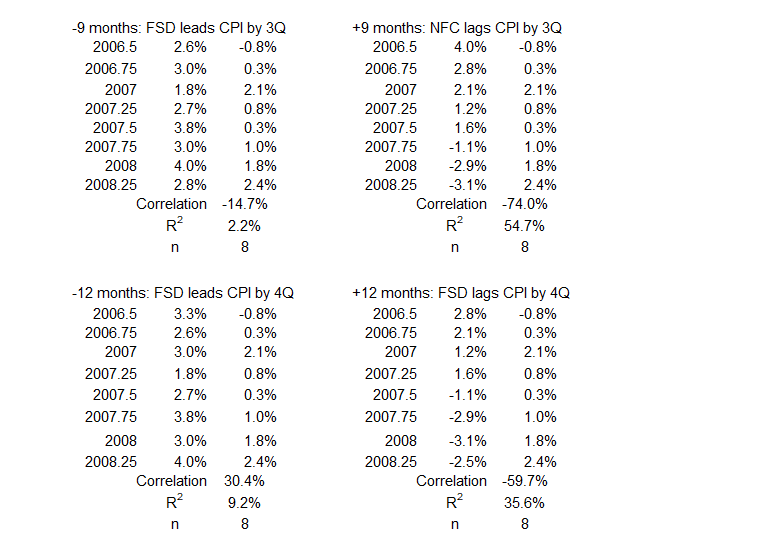

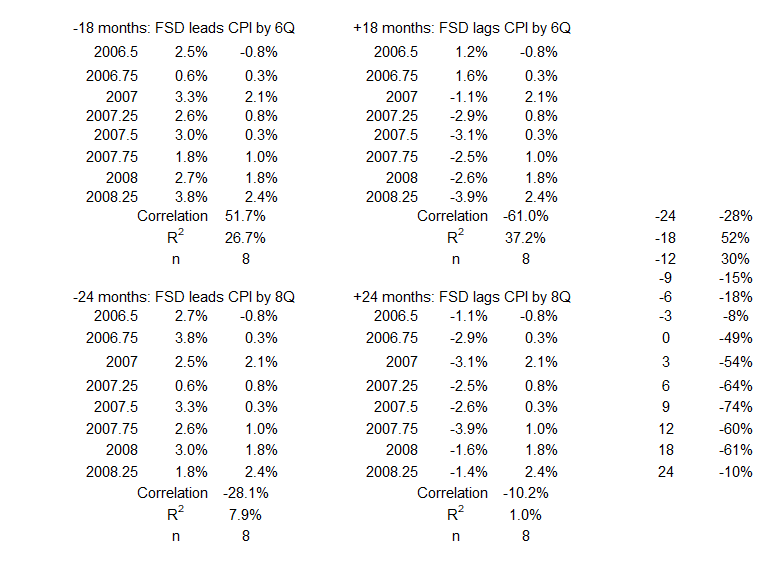

4Q 2006 – 2Q 2008

Figure 19. Financial Sector Debt and Inflation 3Q 2006 – 2Q 2008

This period covers the end of the housing bubble peak and the start of the stock market decline that was part of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-09. Again, we see the familiar pattern for coincident timelines data: A declining trend for financial sectors debt quarterly changes and an increasing trend for CPI inflation changes. Also, there was a one-quarter inflation spike in the first quarter of 2007. For the first time, we are seeing inflation volatility similar to or greater than financial sectors debt.

Figure 20. Quarterly Changes in Financial Sector Debt (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 3Q 2006 – 2Q 2008

As so often the case in this study, the coincident data sets show a negative correlation, this time weak. R = –49% and R2 = 24%. Note that these numbers are just below the lower limit for moderate association.

Figure 21. Correlation Between Financial Sector Debt and CPI Inflation 3Q 2006 – 2Q 2008

Figure 21 is similar to Figures 12 and 15 for the inflation surges from 1972-1974 and from 1977-1980. The negative associations for nonfinancial corporate credit changes coming before CPI Inflation changes are a little stronger here than in Figure 12 and much stronger than in Figure 15. There is some possibility that FSD might have caused up to 25% of the inflation during this period (left side of the graph). There is a greater possibility that increasing inflation might have caused a decline in FSD (right side of the graph).

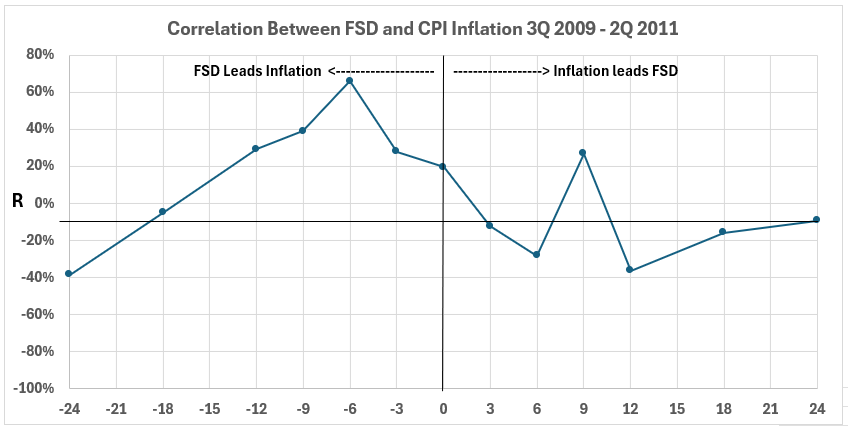

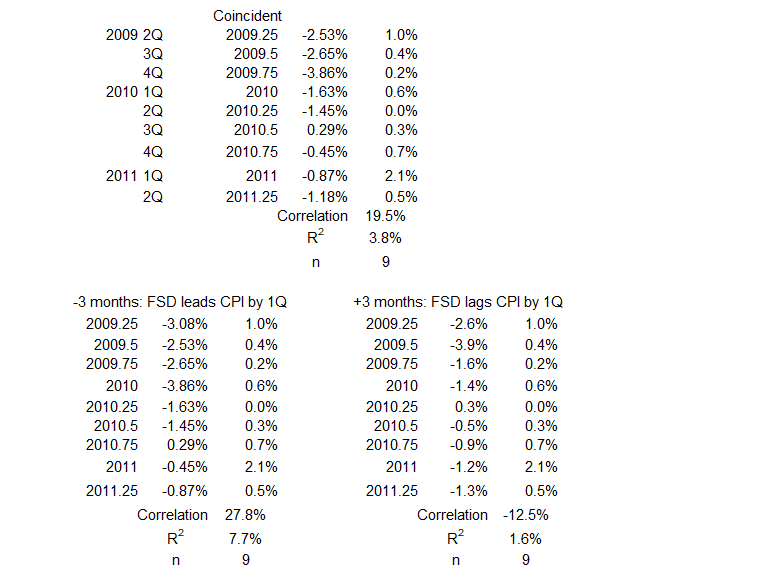

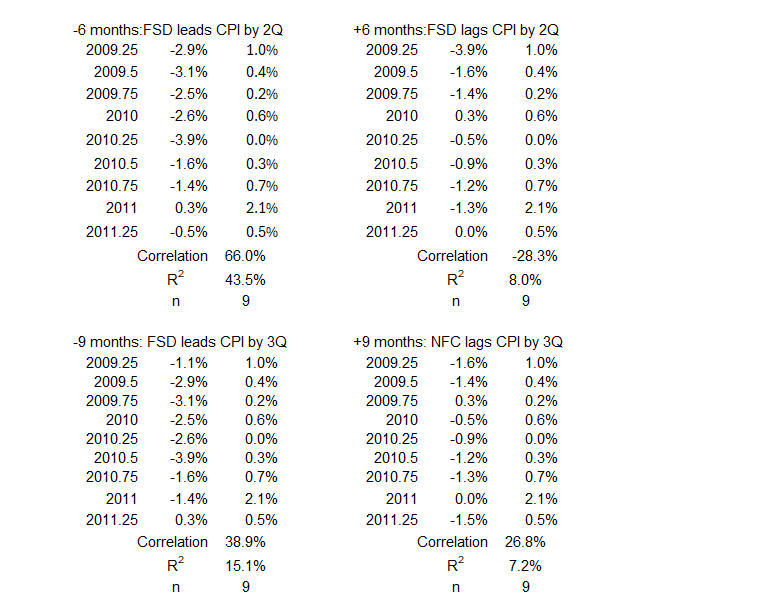

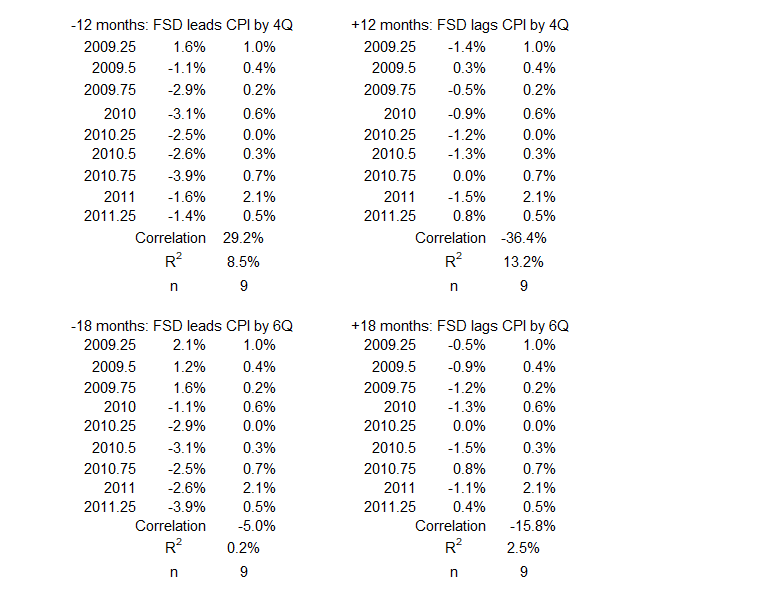

3Q 2009 – 2Q 2011

Figure 22. Financial Sector Debt Debt and Inflation 2Q 2009 – 2Q 2011

This period is like the previous inflation surge (2006-2008), and unlike all previous surges in that, the volatility of FSD is similar to that of CPI, with the exception of the spike in 4Q 2010. The FSD trend is up. The credit change trend (except for the spike in 1Q 2011) is flat. The inflation change trend is nearly flat, except for a small spike one quarter after the credit spike. The fact that the FSD spike is followed by a CPI spike one quarter later suggests that there might by cause and effect.

Figure 23. Quarterly Changes in Financial Sector Debt (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 2Q 2009 – 2Q 2011

A weak positive association exists for the coincident timelines data, R = 20% and R2 = 4%.

Figure 24. Correlation Between Financial Sector Debt and CPI Inflation 2Q 2009 – 2Q 2011

The highest correlation on the left side occurred for FSD leading inflation by 6 months. (Note that this is slightly different from the one-quarter lead time suggested by Figure 22.) Here, R = 66% and R2 = 44%. There are supporting lesser association data points on both sides of this peak. This suggests the possibility that there might be cause and effect at play here.

On the right side, all the associations are negative (weak and negligible), except for the spike to a weak positive correlation at nine months. Rising inflation may not have had any important effect on reducing FSD during this period.

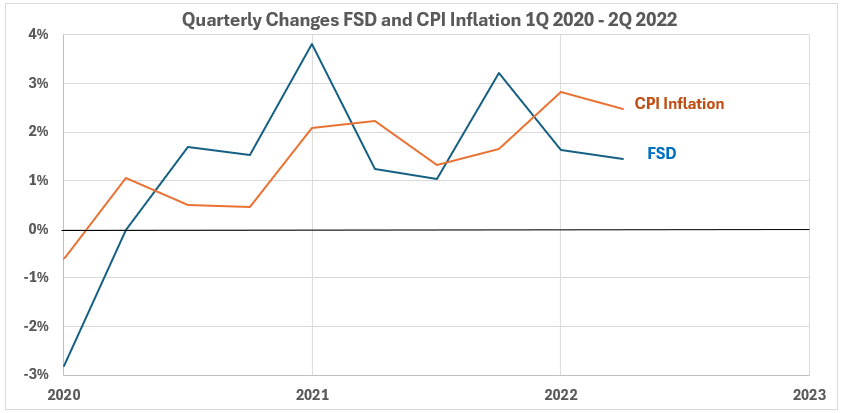

2Q 2020 – 2Q 2022

Figure 25. Financial Sector Debt and Inflation 1Q 2020 – 2Q 2022

During most of this time period (first quarter excepted), both financial sectors changes and inflation changes were in close agreement in magnitude and trend. This was not seen in any other inflation surge period.

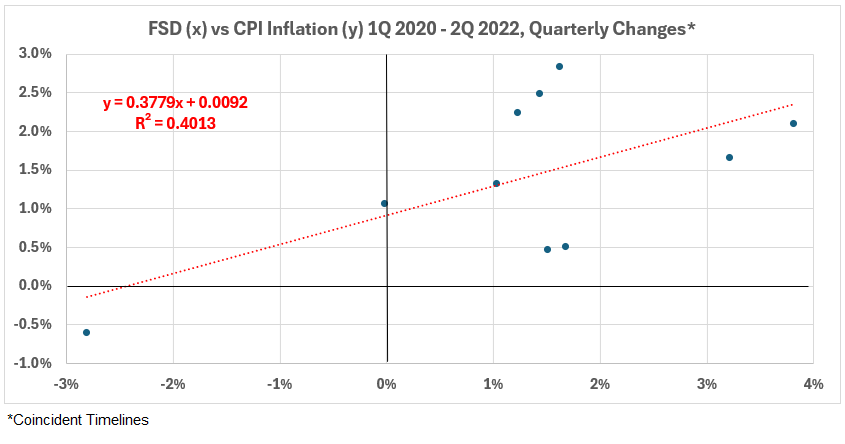

Figure 26. Quarterly Changes in Financial Sector Debt (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 1Q 200 – 2Q 2022

We see a moderate positive association for the concurrent timeline data sets. R = 63% and R2 = 40%.

Figure 27. Correlation Between Financial Sector Debt and CPI Inflation 1Q 2020 – 2Q 2022

There is little in this data to support any meaningful cause-and-effect possibilities between financial sectors debt changes and inflation.

Conclusion

Observations here are somewhat different than previous studies of federal government deficit spending,3 consumer credit,4 mortgage debt,5 and nonfinancial corporate credit.6

Few possibilities exist for meaningful cause-and-effect relationships between changes in financial sector debt (FSD) and changes in inflation for the eight inflation surges between 1952 and 2022, leaving out the cases where only one spike occurred on either side of the correlation graphs.

In drawing these conclusions, we are ignoring associations with 18- and 24-month separations.

There are two occasions where FSD changes could have caused important inflation changes. In the inflation surge of 1972-1974, R2 values indicate it is possible that the credit increases might have caused up to 36% of the inflation. In 2009-2011, up to 44% of the unflation might have been caused by increased FSD. Other information is required to prove that the credit increases caused any of the inflation.

On several occasions, inflation may have been the cause of opposite changes in FSD. These are:

- In 1972-74, inflation changes may account for up to 56% of the opposite change in FSD.

- In 1977-80, inflation changes may account for up to 36% of the opposite change in FSD.

- In 2006-08, inflation changes may account for up to 55% of the opposite change in FSD.

There are fewer possibilities for cause-and-effect relationships between FSD and inflation than for any of the four previous money-creating processes investigated.3,4,5,6 This is not surprising because financial sector debt money is less likely to quickly move into consumers’ hands compared to other money-creating processes.

Further conclusions will be discussed after we have the data for the deflationary surges and the periods with more stable inflation for the 1952-2011 period. More results there next week.

Appendix

Below are the data sets for each period of surging inflation. They come from the tables of timeline alignments1 (Financial Sector Debt and Inflation, Part 1).

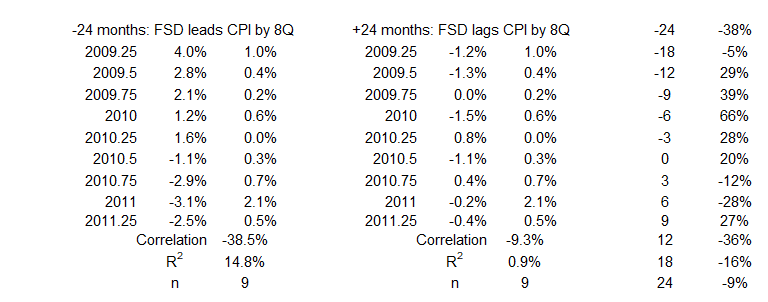

1Q 1955 – 1Q 1957

2Q 1959 – 4Q 1964

1Q 1965 – 4Q 1969

3Q 1972 – 3Q 1974

1Q 1977 – 1Q 1980

1Q 1987 – 3Q 1990

4Q 2006 – 2Q 2008

3Q 2009 – 2Q 2011

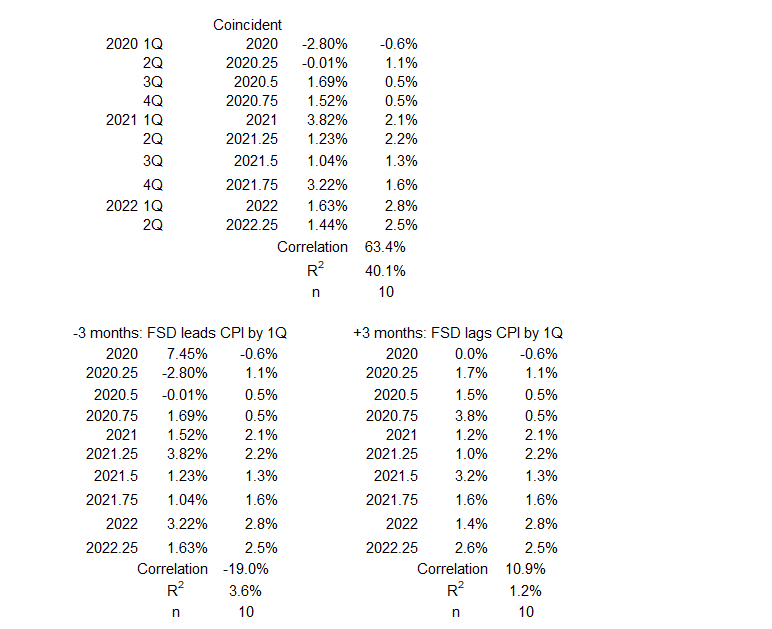

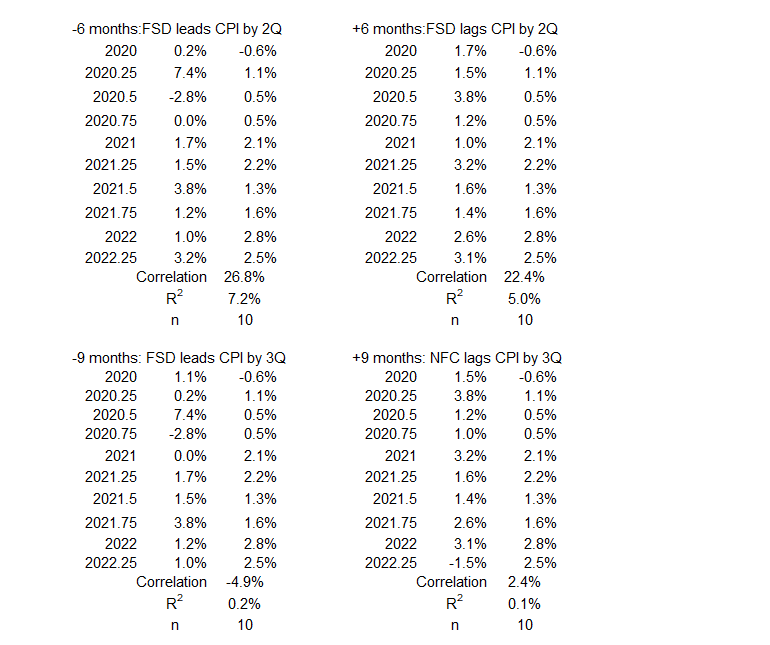

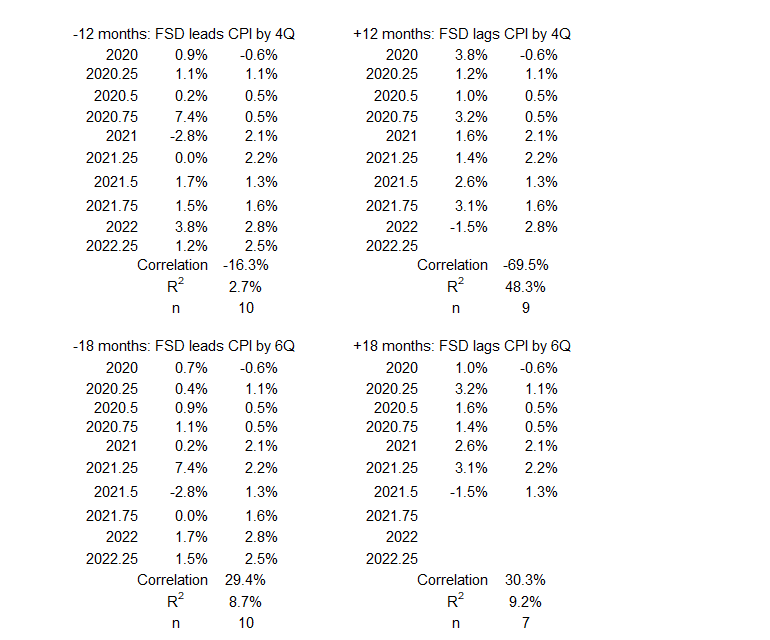

1Q 2020 – 2Q 2022

Footnotes

1. Lounsbury, John, “Financial Sector Debt and Inflation, Part 1″, EconCurrents, March 10, 2024. https://econcurrents.com/2024/03/10/financial-sector-debt-and-inflation-part-1/.

2. Lounsbury, John, “Consumer Credit and Inflation: Part 1”, EconCurrents, September 3, 2023. https://econcurrents.com/2023/09/03/consumer-credit-and-inflation-part-1/.

3. Lounsbury, John, “Government Spending and Inflation. Reprise and Summary”, EconCurrents, August 20, 2023. https://econcurrents.com/2023/08/20/government-spending-and-inflation-reprise-and-summary/.

4. Lounsbury, John, “Consumer Credit and Inflation: Part 4”, EconCurrents, September 23, 2023. https://econcurrents.com/2023/09/23/consumer-credit-and-inflation-part-4/.

5. Lounsbury, John, “Mortgage Debt and Inflation: Part 4”, EconCurrents, October 22, 2023. https://econcurrents.com/2023/10/22/mortgage-debt-and-inflation-part-4/.

6. Lounsbury, John, “Nonfinancial Corporate Credit and Inflation: Part 4”, EconCurrents, March 3, 2024 https://econcurrents.com/2024/03/03/nonfinancial-corporate-credit-and-inflation-part-4/.

7. Freedman, David, Pisani, Robert, and Purves, Richard, Statistics, Fourth Edition, W.W. Norton & Company (New York) and Viva Books (New Delhi), 2009. See Chapters 8 & 9 for an explanation of how normal distributions relate to determining correlation coefficients. See p. 147 for a discussion of football-shaped scatter diagrams.