Two studies have been performed on the correlations between U.S. Federal Deficit Spending and CPI Inflation. The first used federal deficits for fiscal years between 1914 and 2022. The second study used the quarterly data available for federal deficit spending starting in 1966. This article compares the results of the two studies.

Photo by Indira Tjokorda on Unsplash

Introduction

In these studies, the inflation time series has periods of inflationary surges, deflationary surges, and years when inflation/disinflation/deflation have trends with <4% change uninterrupted by countertrend moves >1.5%. However, the data organizations were different for each of the two studies.

In the first study, annual inflation was used to determine periods of inflation and deflationary surges. In the second study, inflation was examined quarterly. This led to different definitions of inflation and disinflation periods. These differences may or may not have produced different conclusions about the associations between deficit spending and inflation. These differences are examined here for the years 1966 through 2022. Quarterly deficit spending data is not available before 1966.

Data

Annualized Inflation

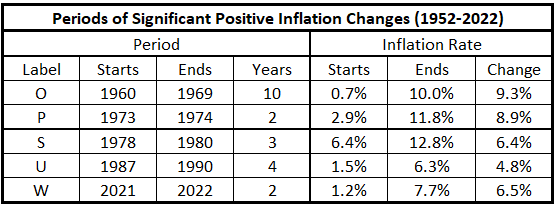

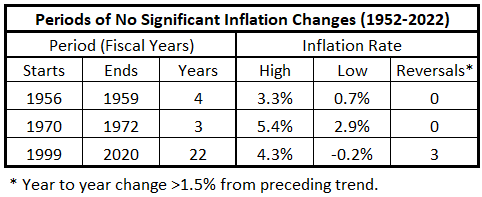

Inflationary period definitions were made in the original federal deficit spending and consumer inflation study.1 The three types of inflationary periods (inflationary surges, disinflationary surges, and no surges) from 1952 to 2022 are in Tables 1-3. For the definition of the various periods, see “Government Spending and Inflation: Reprise and Summary”.1

Table 1. Periods of Significant Increases of Inflation 1952-2022

Table 2. Periods of Significant Decreases of Inflation 1952-2022

Table 3. Periods without Significant Inflation Trends 1952-2022

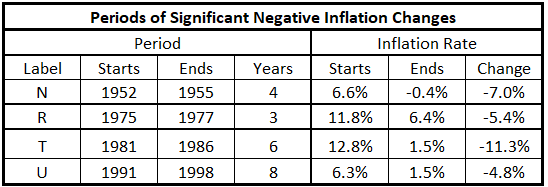

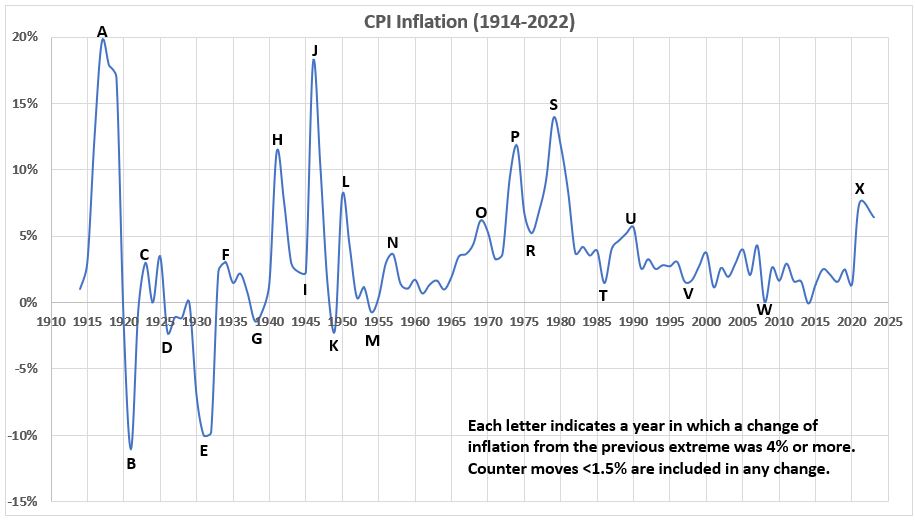

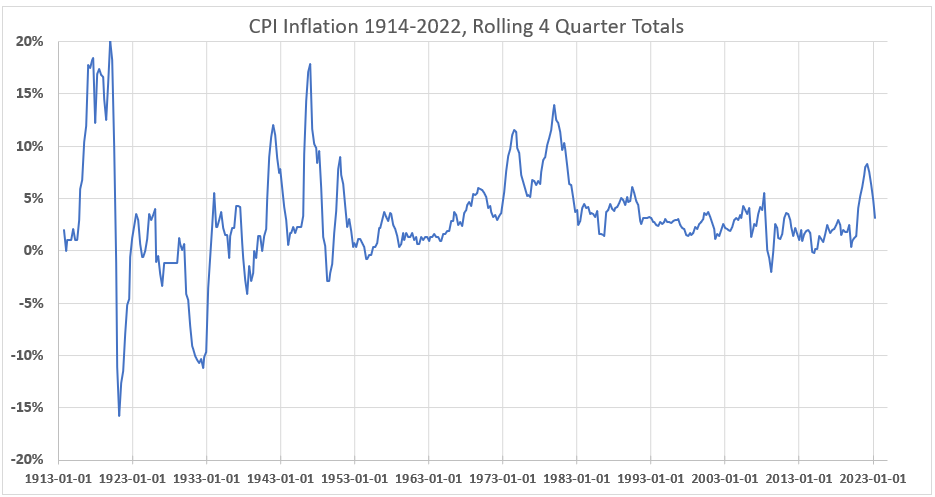

The previous work,1 using annual data, produced the inflation time series graph shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. CPI Annual Inflation 1914-2022 with Significant Changes in Inflation Noted

(Each letter identifies the end of a significant move.)

The data in Figure 1 produced Tables 1-3.

Inflation Measured Quarterly

Figure 2 shows the rolling four-quarter inflation using quarterly data. This results in four times as many data points for 12 months of inflation over the same 109 years.

Figure 2. CPI Rolling Four Quarter Inflation 1914-2022

There is much more structure in Figure 2 than in Figure 1. This may reflect noise in the Figure 2 data or be real information. The only area where this question may have importance could be the three peaks from 3Q 1917 to 1Q 1920. In Figure 1, this time period shows only a single peak with a shoulder approaching 1920. Addressing this question has no bearing on the current study, which covers the 71 years 1952-2022.

Figure 3 displays the inflation data for the study period 1952-2022.

Figure 3. CPI Rolling Four Quarter Inflation 1952-2022 with Significant Changes in Inflation Noted

(Each letter identifies the end of a significant move. An * identifies the end of an insignificant time period.)

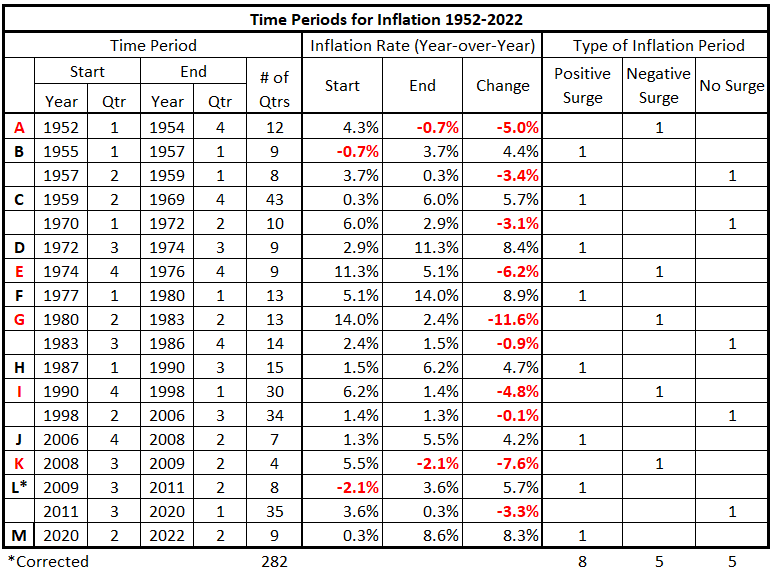

A summary of the data in Figure 3 is in Table 4.

Table 4. Timeline of Inflation Data 1952-2022

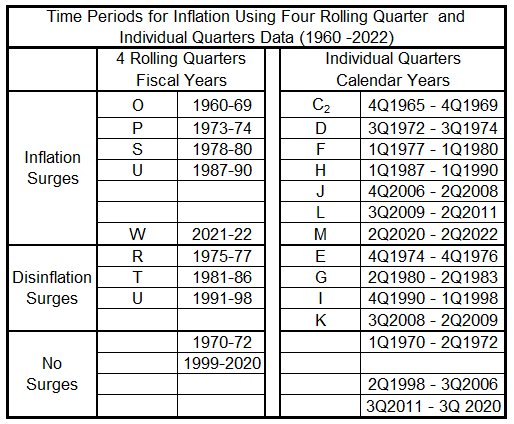

Periods of Inflation Behavior for the Two Data Organizations

Table 5 shows the comparisons for Tables 1, 2, and 3 with the data in Table 4. With the exception of 1987-90, one-to-one correspondence for periods of various inflation behaviors does not exist for the two data organizations (annual deficit data and quarterly deficit data).

Table 5. Inflation Periods – Two Data Organizations (1960-2022)

Analysis

Inflation Surges

This analysis uses previously determined timeline displacement correlations between federal deficit spending (FDS) and consumer price inflation (CPI). The timeline displacements are

- Federal Deficit Spending and CPI Inflation quarters are coincident.

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by one quarter (±3 months)

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by two quarters (±6 months)

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by three quarters (±9 months)

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by four quarters (±12 months)

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by six quarters (±18 months)

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by eight quarters (±24 months)

The analysis that produced the graphs below for annual deficit spending over fiscal years is here.2,3

The 1960s

The time overlap between the two data sets for the 1960s is not close. The quarterly deficit data do not start until the decade is more than half over.

Figure 4. Correlation of FDS and CPI, Fiscal Years (1960-69)

Figure 5. Correlations of Quarterly FDS and CPI, Calendar Years (1965-69)

The general observation is that the fiscal year data shows a more positive association between FDS and CPI than the quarterly deficit data from 1965 through 1969. However, the comparison should be tempered by the significant difference between the two time spans. Additionally, the associations for the left side of Figure 4 are weak, with R2 values ranging from 15% to nearly zero. This indicates that at least 85% of inflation in the 1960s resulted from causes other than federal deficits.

Looking at the right sides of the two graphs, Figure 4 indicates that up to 30% of increased federal deficits in the 1960s might have been caused by consumer inflation. On the other hand, Figure 5 shows much less possibility that increased CPI might have been the cause of federal deficits in the second half of the 1960s.

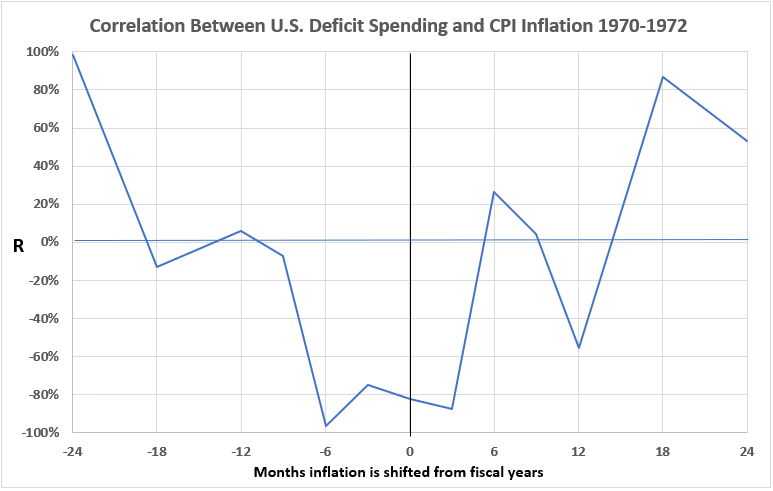

The Early 1970s

Figure 6. Correlation of FDS and CPI, Fiscal Years (1970-72)

Figure 7. Correlations of Quarterly FDS and CPI, Calendar Years (1972-74)

The fiscal year data set and the quarterly data set for federal deficit sending in the two early 1970 time periods both show no positive associations for FDS timelines leading CPI. The only exception is when FDS leads CPI by two years, as shown in Figure 6.

The results for the CPI timelines leading FDS are different for Figure 6 and Figure 7. In Figure 6, for CPI leading FDS by up to one year, the associations are moderate and large (negative) and very small or negligible (positive). This indicates that a very small or nihil cause-and-effect is possible for CPI producing increased DFS in 1970-72 with lead times up to one year. The large positive association at 18 months, R = 84% and R2 = 71%, suggests delayed causation may exist. Up to ~70% of increased federal spending may have been caused by CPI inflation a year and a half earlier during the 1970-72 period.

Figure 7 shows a large association between CPI and FDS for many lead time intervals for CPI. For 1972-74, up to ~60% of increased FDS may have been due to previous increases in CPI.

Note the use of emphasis. Correlation does not prove causation. It only indicates causation is possible.

The Late 1970s

Figure 8. Correlation of FDS and CPI, Fiscal Years (1978-80)

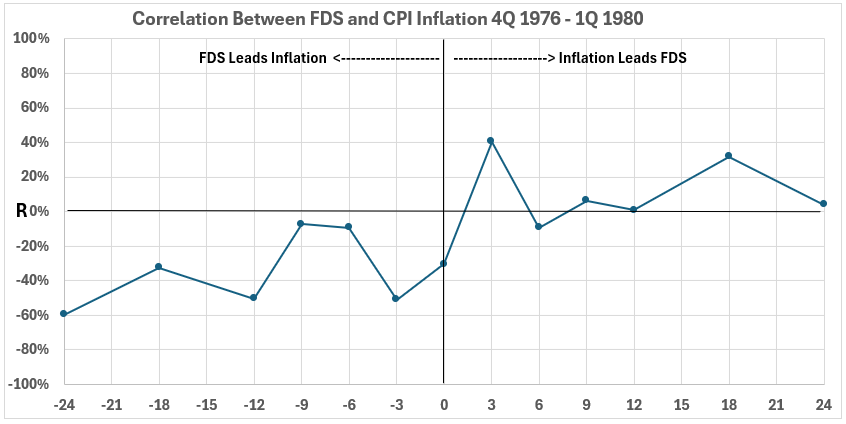

Figure 9. Correlations of Quarterly FDS and CPI, Calendar Years (1977-80)

Figure 8 shows a moderate positive association when FDS increases occurred two years before CPI increases. Otherwise, both data organizations show negative associations between FDS increases and subsequent CPI increases. For the late 1970s, there is no possibility that increasing federal deficits caused increased consumer inflation.

There is also little possibility that increased CPI caused increased FDS in the late 1970s. The highest R2 values are 16% (right side Figure 9) and 10% (right side Figure 8). This indicates that at least 84-90% of increased federal deficit spending was caused by something other than CPI inflation.

The Late 1980s

Figure 10. Correlation of FDS and CPI, Fiscal Years (1987-90)

Figure 11. Correlations of Quarterly FDS and CPI, Calendar Years (1987-90)

Two data points show positive associations of note in Figures 10 and 11. When FDS leads CPI by 18 months, R2 ~ 30% (Figure 10), and when CPI leads FDS by 18 months, R2 ~ 10% in Figure 11. All other associations are negligible or negative. There is little possibility that in the late 1980s, there was any positive causation for FDS to increase CPI or vice versa.

The Early 2020s

There is insufficient data for analysis of fiscal year CPI inflation corrections with federal deficit spending.

Figure 12. Correlations of Quarterly FDS and CPI, Calendar Years (2020-22)

With the exception of FDS leading inflation by two years, there is only one data point with a positive (and non-negligible) association. For FDS leading CPI by 12 months, R2 ~ 6%. All other data points indicate that higher federal deficit sending did not cause increased CPI inflation and vice versa.

Conclusion

For periods with positive inflation surges, the correlation between annual U.S. federal deficit spending (FDS) and CPI inflation is not substantially different from the analysis done with quarterly deficit spending changes, with one exception: The quarterly data shows a significant association for inflation with subsequent deficit spending for 1972-74. The four-quarter data (fiscal years) does not show a strong association for 1970-72. Both data organizations show limited evidence for the possibility that increased FDS produced increased CPI.

The data indicate that increased CPI might have caused increased FDS only in one period (1972-74). However, correlation by itself cannot prove causation.

Next week, we will compare the disinflationary surges and periods without surges using the two data organizations.

Footnotes

1. Lounsbury, John, “Government Spending and Inflation. Reprise and Summary,” EconCurrents, August 20, 2023. https://econcurrents.com/2023/08/20/government-spending-and-inflation-reprise-and-summary/.

2. Lounsbury, John, “Government Spending and Inflation. Part 13B”, EconCurrents, June 25, 2023. https://econcurrents.com/2023/06/25/government-spending-and-inflation-part-13b/

3. Lounsbury, John, “Government Spending and Inflation. Part 13B – Addendum”, EconCurrents, June 30, 2023. https://econcurrents.com/2023/07/30/government-spending-and-inflation-part-13b-addendum/.