The full data sets for the 56 years from 1966 to 2022 show no discernable association patterns (correlations) for federal deficit spending (FDS) and inflation changes.1 Thus, we started an analysis by looking specifically at the various regimes of inflation change during the 56-year timeline. The most recent post2 analyzed the seven time periods over 56 years with positive inflation surges. This article analyzes the association between CPI changes and FDS changes during the four periods from 1966 to 2022 with negative inflation (disinflation/deflation) surges.

Image by Nicolae Baltatescu from Pixabay.

Introduction

The 71 years from 1952 to 2022 are divided into three types of inflationary behavior:1

- Significant inflation increases;

- Significant inflation decreases;

- No significant inflation changes.

An inflation change is significant if it is ≥4.0% with no intervening countertrend change >1.5%.

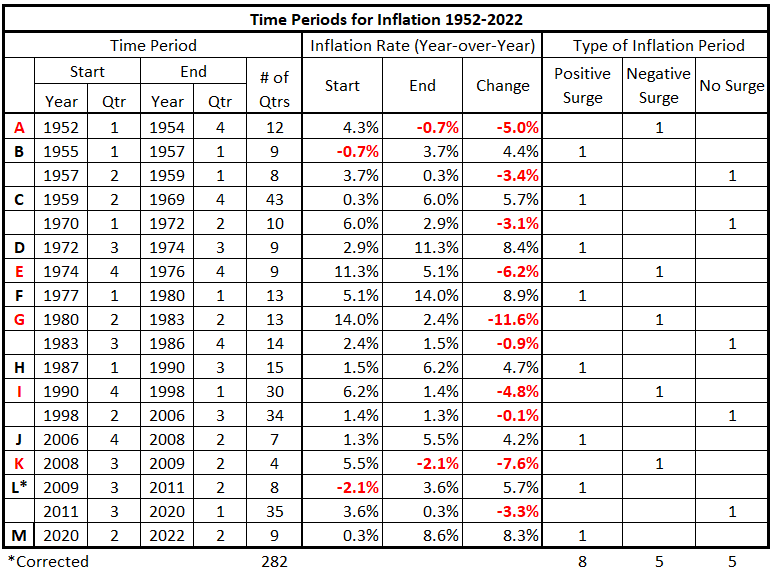

Previously, we defined the partitioning of inflation into the pattern in Table 1.

Table 1. Timeline of Inflation Data 1952-2022 (Previously Table 4*.1)

We will examine each category of inflation behavior separately. In this piece, we analyze the significantly negative periods of inflation (disinflation and deflation surges).

Data

The data is from Tables 5-17, prepared previously.1

There are 13 quarterly timeline alignments:

- Federal Deficit Spending and CPI Inflation quarters are coincident.

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by one quarter (±3 months)

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by two quarters (±6 months)

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by three quarters (±9 months)

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by four quarters (±12 months)

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by six quarters (±18 months)

- Federal Deficit Spending leads and lags CPI Inflation by eight quarters (±24 months)

Analysis

4Q 1974 -4Q 1976

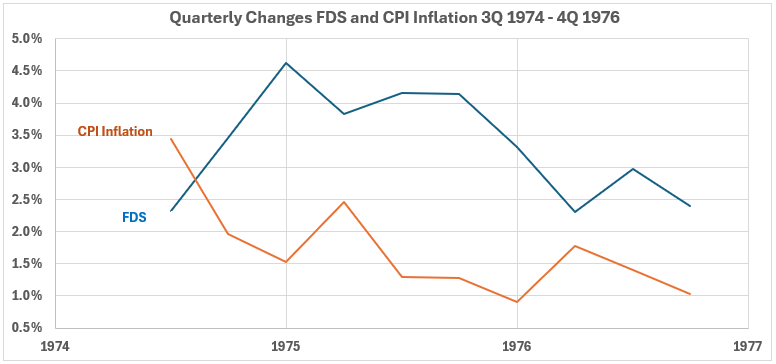

Figure 1. U.S. FDS and Inflation 4Q 1974 – 4Q 1976

FSD changes increased for two quarters and then declined. CPI changes were in a general downward trend throughout the period. Volatility for the two variables was similar.

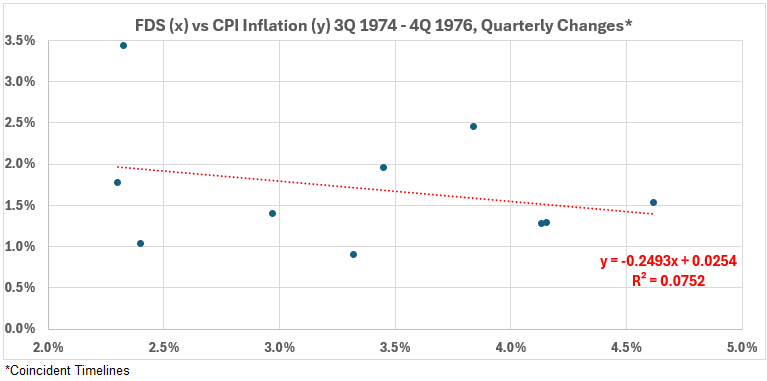

Figure 2. Quarterly Changes in FDS (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 4Q 1974 – 4Q 1976

When the data timelines coincide, the overall association between these two variables is very small and positive. R = 27% and R2 = 7.5%.

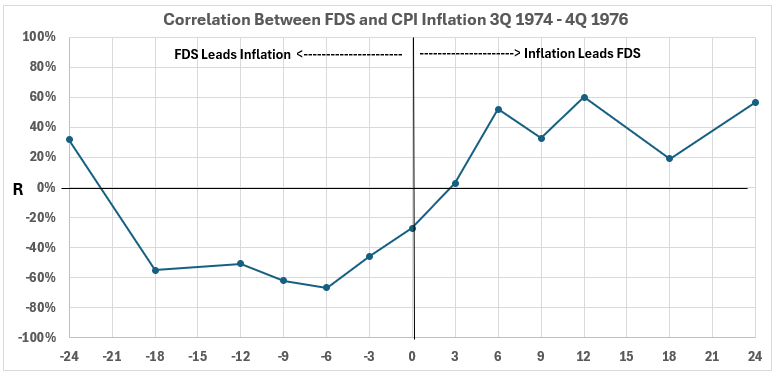

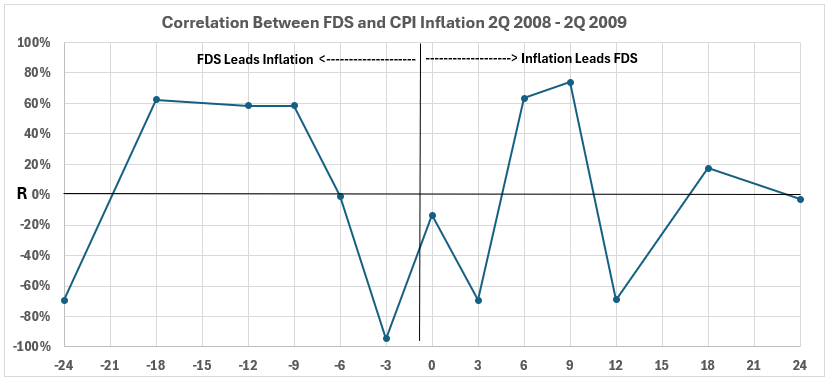

Figure 3. Correlation Between FDS and CPI Inflation 4Q 1974 – 4Q 1976

The negative association of FSD with inflation is moderate when debt changes come before inflation. On the left side of the graph, there are four values for R2, ranging from 45% to 26%.

The strongest correlations on the right side are moderate and positive, occurring when inflation changes come before debt changes. At 6 and 12 months, R2 values are 27% and 35%, respectively.

The data here is for periods of disinflation. So, a negative association between FDS changes and CPI changes indicates that larger FDS changes are associated with smaller CPI changes. That is the opposite of what would occur if larger FDS was causing inflation.

The result on the right side of Figure 3 shows that a moderate association exists for two data points. In this case, changes in CPI are associated with changes in the same direction for subsequent deficit spending. Since this is a disinflationary period, this means it is possible that less inflation might cause less deficit spending.

This is a good time to remind ourselves that association only means cause-and-effect might be possible. Other information is needed to determine if there is any causation at all.

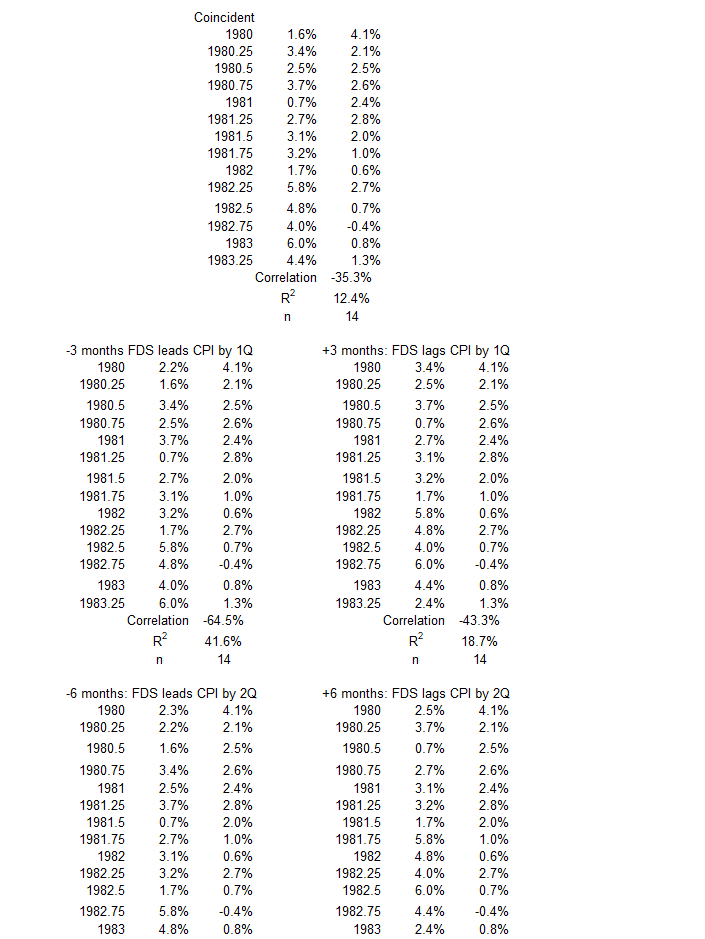

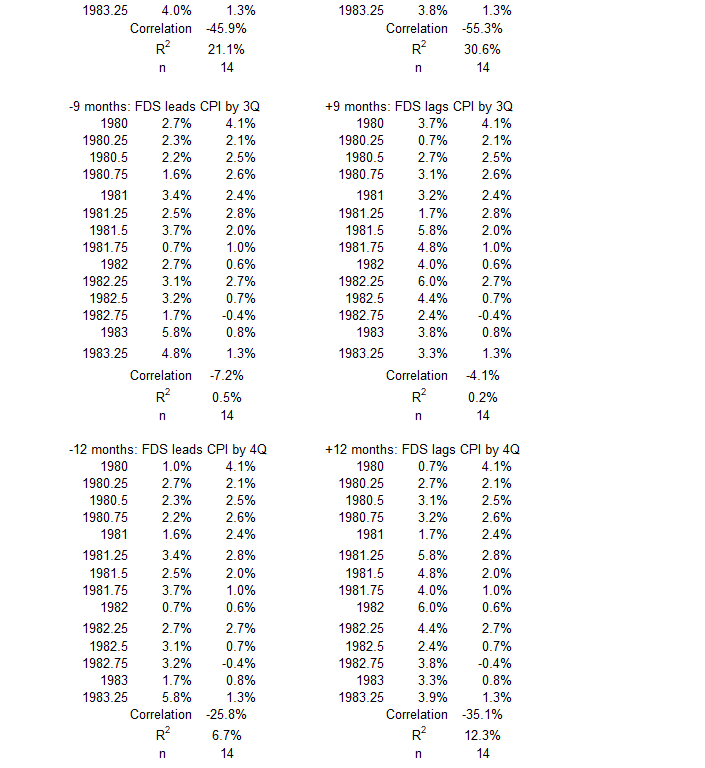

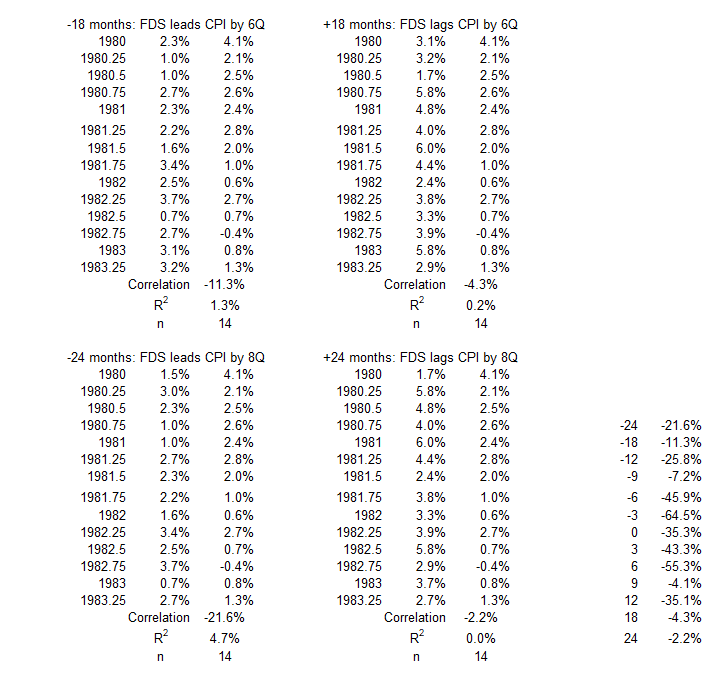

2Q 1980 – 2Q 1983

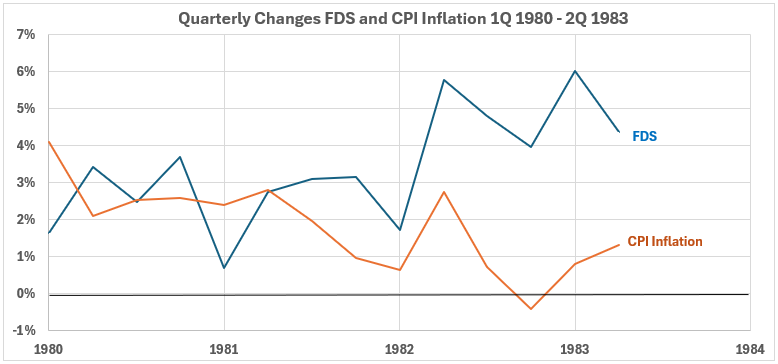

Figure 4. U.S. FDS and Inflation 1Q 1980 – 2Q 1983

The trends for FDS changes and the CPI Inflation changes trend generally in opposite directions throughout the period. The relative volatilities for the two variables are similar in this period but a little larger for FDS.

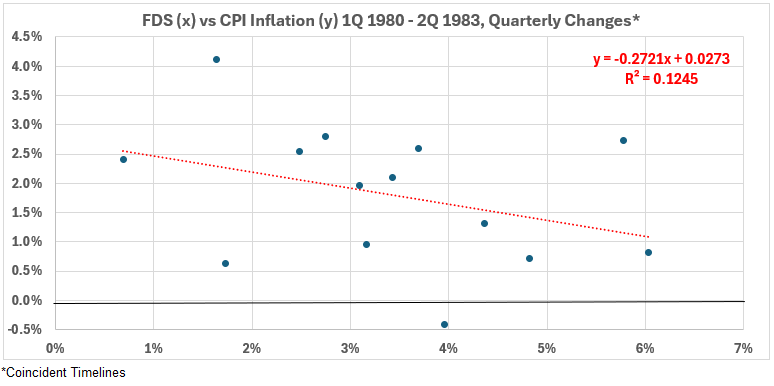

Figure 5. Quarterly Changes in FDS (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 1Q 1980 – 2Q 1983

The correlation when the two data timelines coincide is negative and weak. R = –35% and R2 = 12%.

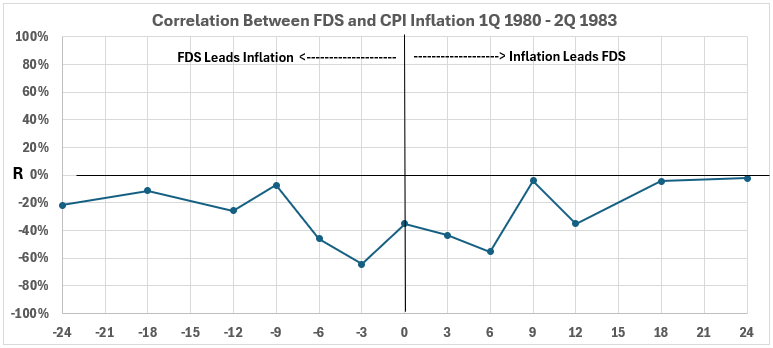

Figure 6. Correlation Between FDS and CPI Inflation 1Q 1980 – 2Q 1983

All associations here are negative, and most are weak. Since this is a deflationary period, we need to focus on negative changes in CPI when considering possible causes and effects. The results on the left side of Figure 6 are the opposite of what would occur if increasing deficit spending was causing increasing inflation. This result is the same as for the previous deflationary period (Figure 3).

The right side of Figure 6 is consistent with declining inflation contributing to the causes of declining deficit spending. This seems reasonable but is not proof. Remember, correlation is not causation.

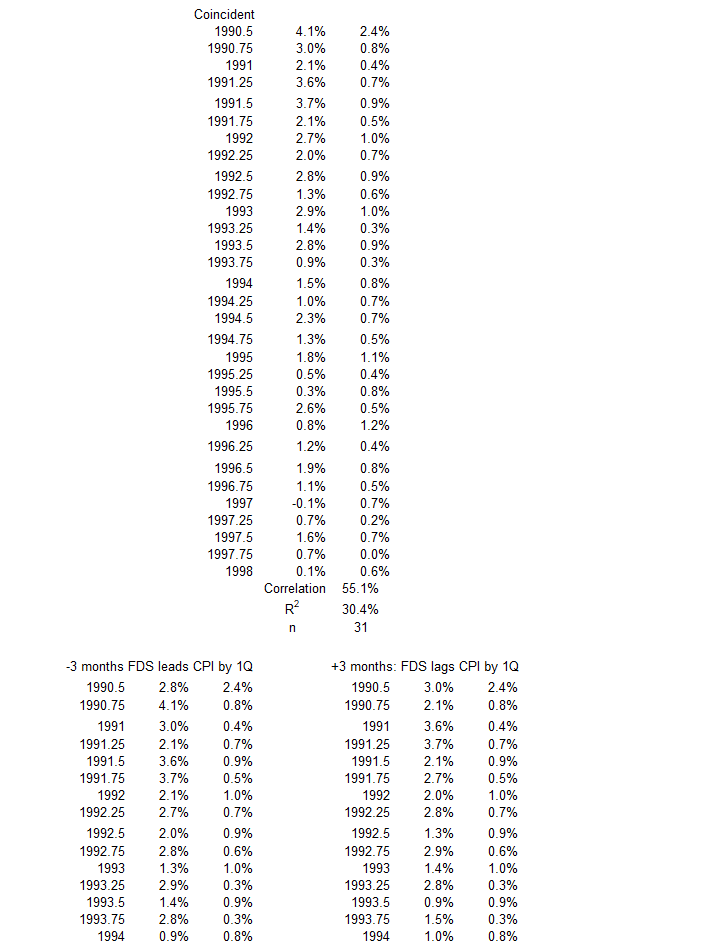

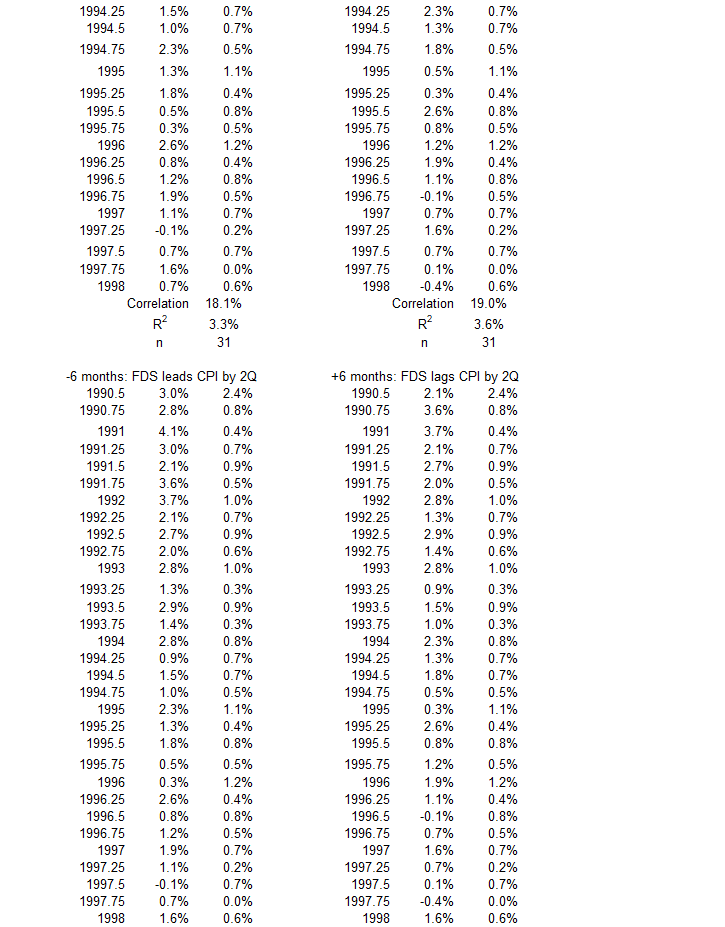

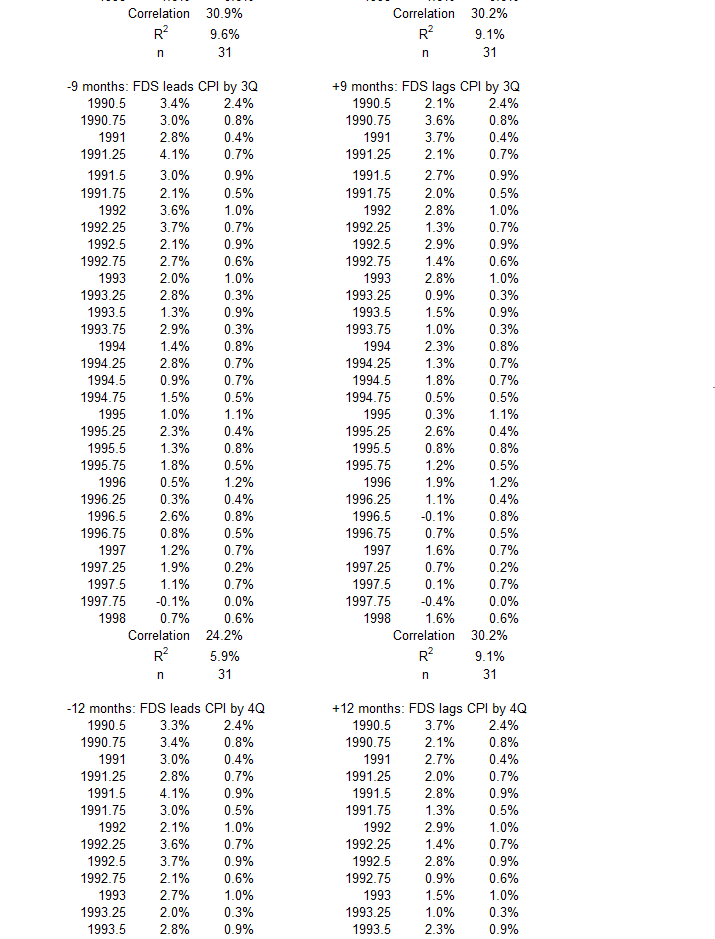

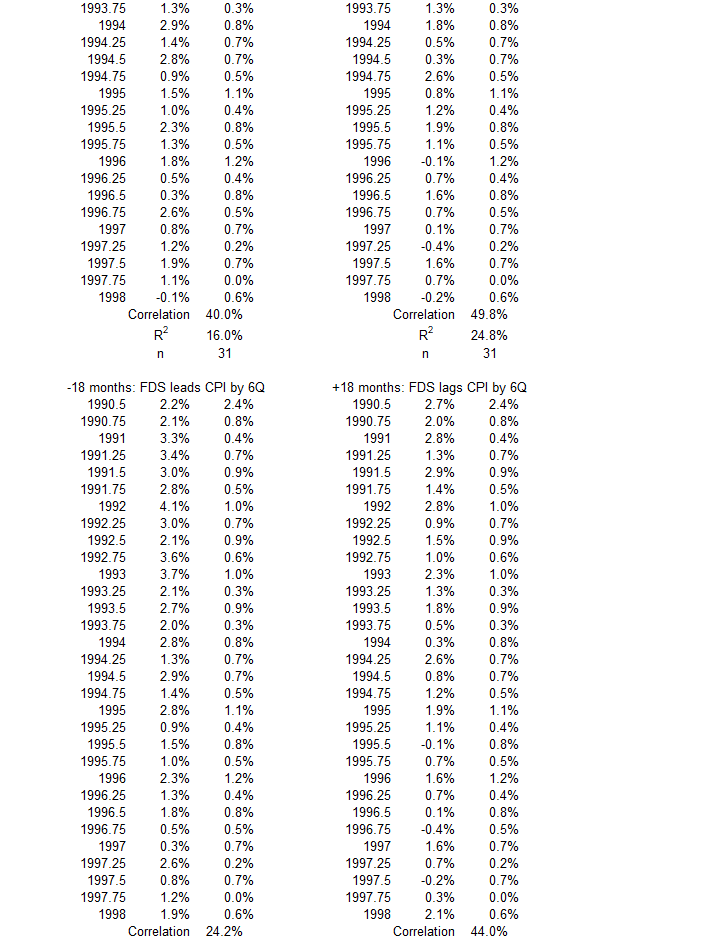

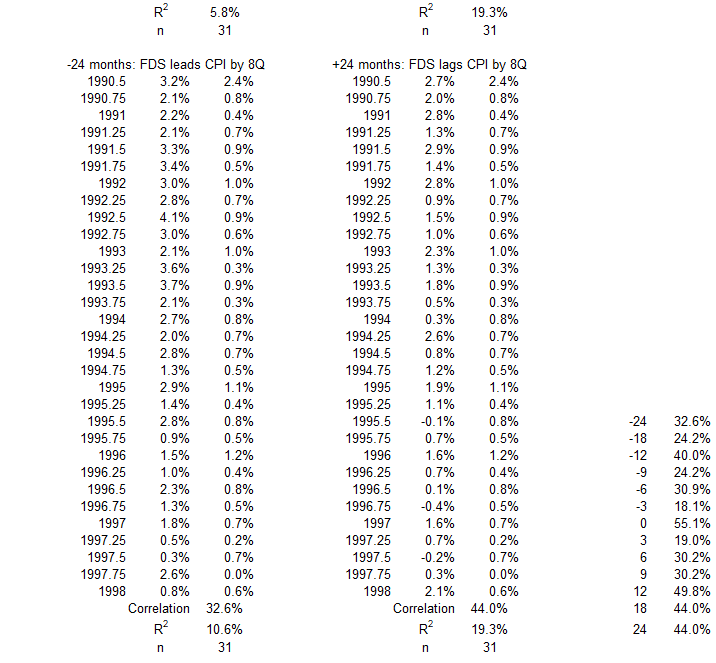

4Q 1990 – 1Q 1998

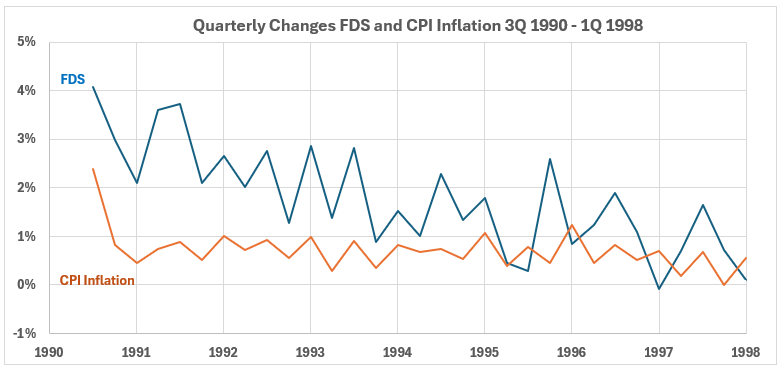

Figure 7. U.S. FDS and Inflation 3Q 1990 – 1Q 1998

Federal deficit spending changes and CPI inflation changes are both in downward trends during this decade. FDS has a stronger trend and more volatility compared to CPI.

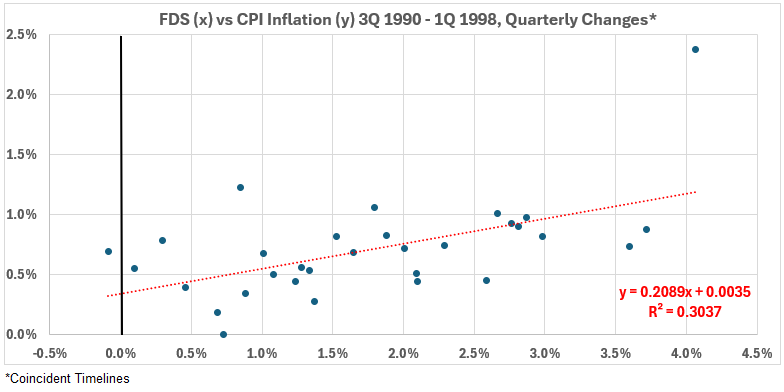

Figure 8. Quarterly Changes in FDS (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 3Q 1990 – 1Q 1998

The scatter plot (Figure 11) confirms the general observation made for Figure 7: There is a moderate positive association between coincident federal deficit spending changes and inflation during the 1990s. R = 55% and R2 = 30%.

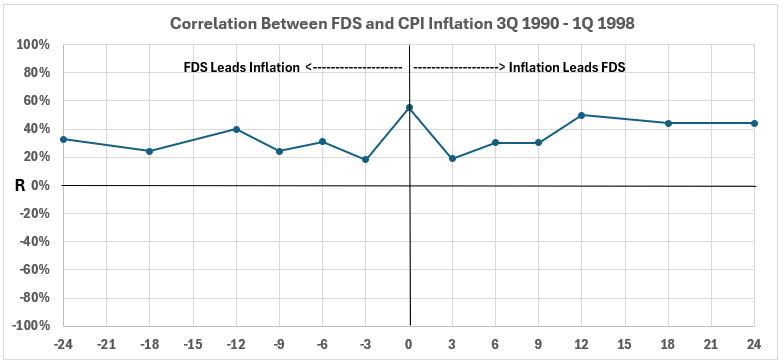

Figure 9. Correlation Between FDS and CPI Inflation 3Q 1990 – 1Q 1998

Figure 9 shows limited opportunity for major cause-and-effect relationships when FDS changes come before inflation (left side of the graph) or when inflation changes come before FDS (right side of the graph). Except for coincident timeline data, all associations are weak or very weak.

The positive correlations indicate that decreasing changes in FDS might contribute to decreasing changes in CPI Left side of the graph).

The right side of the graph indicates that declining changes in CPI might contribute to decreasing changes in FDS,

Caveat: Possibility does not prove anything. Additional information is needed for cause-and-effect proof.

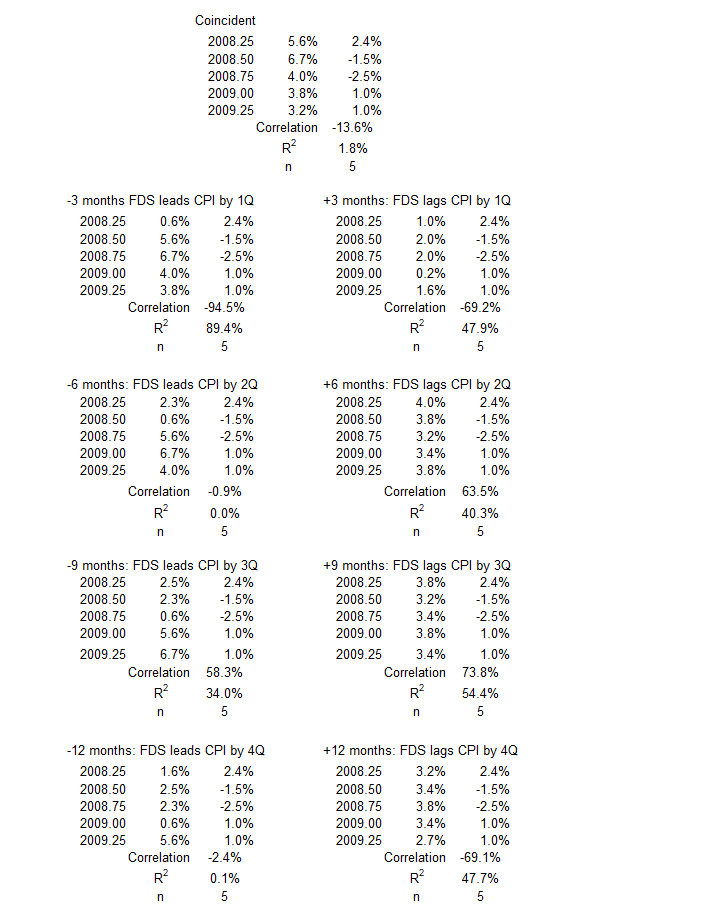

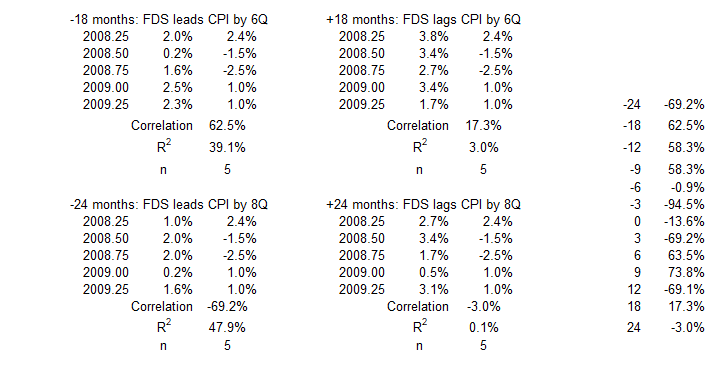

3Q 2008 – 2Q 2009

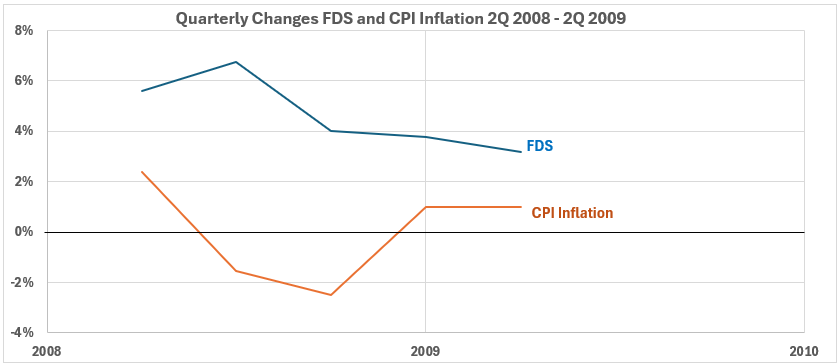

Figure 10. U.S. FDS and Inflation 3Q 2008 – 2Q 2009

The two variables show three quarters of opposing changes and one quarter with parallel changes.

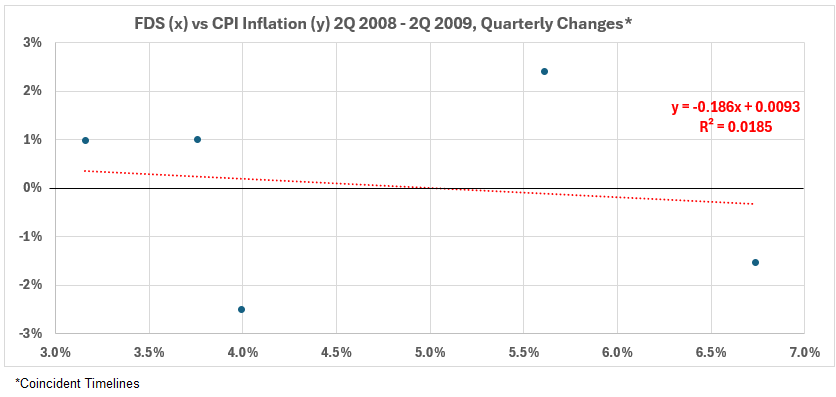

Figure 11. Quarterly Changes in FDS (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 3Q 2008 – 2Q 2009

There is a lot of scatter in Figure 11, suggesting that analysis of this small data set may offer some problems. For a discussion, see this.3 The association here is very weak: R = 14% and R2 = 1.8%.

Figure 12. Correlation Between FDS and CPI Inflation 3Q 2008 – 2Q 2009

The very small data sample makes extracting any meaning from Figure 12 problematic. Wide swings in the correlations among the various timeline offsets add to the reluctance to attempt an interpretation.

Conclusion

The results here are inconsistent with the possibility that increasing federal deficit changes could have contributed to the causes of increasing inflation.

These results indicate the possibility that decreasing FDS changes might have contributed to decreasing CPI inflation in the 1990-1998 period.

The results for 1974-1976 and 1990-1998 indicate that decreasing changes in inflation might have contributed to decreasing changes in deficit spending.

After analyzing periods with no significant inflation changes, there will be more discussion of the results. That comes next week.

Appendix

Below are the data sets for each significant negative inflation (disinflation and deflation) period. They come from the tables of timeline aligments1 (Federal Deficit Spending and Inflation: Part 1).

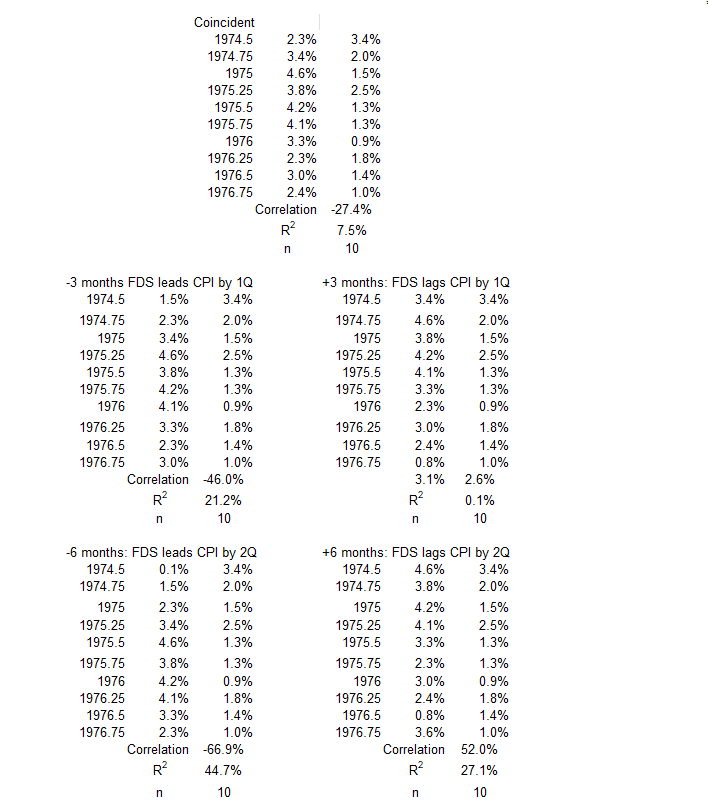

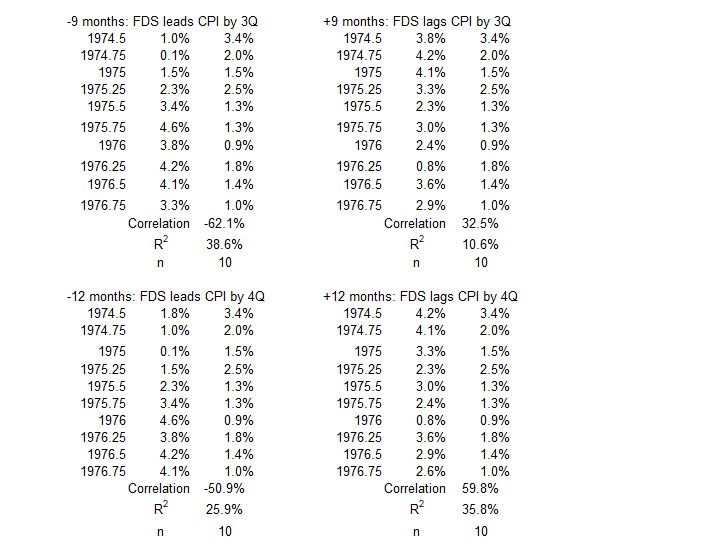

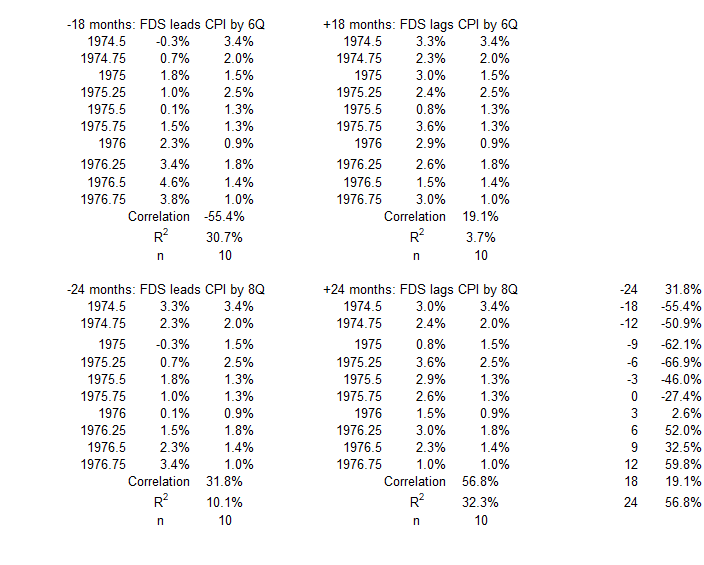

4Q 1974 -4Q 1976

2Q 1980 – 2Q 1983

4Q 1990 – 1Q 1998

3Q 2008 – 2Q 2009

Footnotes

1. Lounsbury, John, “Federal Deficit Spending (Quarterly) and Inflation. Part 1″, EconCurrents, April 7, 2024. https://econcurrents.com/2024/04/07/federal-deficit-spending-quarterly-and-inflation-part-1/.

2. Lounsbury, John, “Federal Deficit Spending (Quarterly) and Inflation. Part 2″, EconCurrents, April 14, 2024. https://econcurrents.com/2024/04/14/federal-deficit-spending-quarterly-and-inflation-part-2/.

3. Hole, Graham, “Eight things you need to know about interpreting correlations,” Research Skills One, Correlation interpretation, Graham Hole v.1.0., October 5, 2015. https://users.sussex.ac.uk/~grahamh/RM1web/Eight%20things%20you%20need%20to%20know%20about%20interpreting%20correlations.pdf.

John,

Excellent work and analysis. Looking forward to next week’s article.

Thanks, Gary.