This article concludes the analysis of the correlation patterns between Financial Sector Debt (FSD) and Consumer Inflation (CPI). The last of the three types of inflation patterns (time periods with no significant inflation trends) is the subject of analysis here. The other two types of patterns (inflation surges1 and disinflation/deflation surges2) were analyzed previously. The conclusion discusses the correlation patterns for all time periods, looks for any common threads, and identifies important differences across time periods and types of correlation patterns.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay.

Introduction

The hypothesis we are testing is that inflation depends on nonfinancial corporate credit in a linear manner, expressed in the following equation:3

I = mS + b

where

I = Change in CPI (the Consumer Price Index)

S = Change in Financial Sector Debt

Data

The data sources3 and tables for FSD and CPI are in Part 1. The timelines3 for the two data sets in Part 1 have coincident timelines and offsets by three and six months out to 24 months for FSD coming before CPI and vice versa.

The inflation timeline from 1952 through 2022 uses year-over-year inflation calculated quarterly. Figure 1 shows the inflation graph for the 1952-2022 time period (from Part 1).

Figure 1. CPI Rolling Four Quarter Inflation 1952-2022 with Significant Changes in Inflation Noted

(Each letter identifies the end of a significant move. An * identifies the end of an insignificant time period.)

Table 1 shows the data from Figure 1.

Table 1. Timeline of Inflation Data 1952-2022 (Previously Table 4*.1)

In Table 1, a black letter identifies a significant positive surge in inflation, a red letter for significant negative surges, and no letter for time periods with no significant changes in inflation.

Significant surges are changes in inflation ≥4% with no intervening countertrend moves >1.5%.

Analysis

There are 13 quarterly timeline alignments examined in each of the 5 time periods:

- FSD and CPI Inflation quarters are coincident.

- FSD leads and lags CPI Inflation by one quarter (±3 months)

- FSD leads and lags CPI Inflation by two quarters (±6 months)

- FSD leads and lags CPI Inflation by three quarters (±9 months)

- FSD leads and lags CPI Inflation by four quarters (±12 months)

- FSD leads and lags CPI Inflation by six quarters (±18 months)

- FSD leads and lags CPI Inflation by eight quarters (±24 months)

2Q 1957 – 1Q 1959

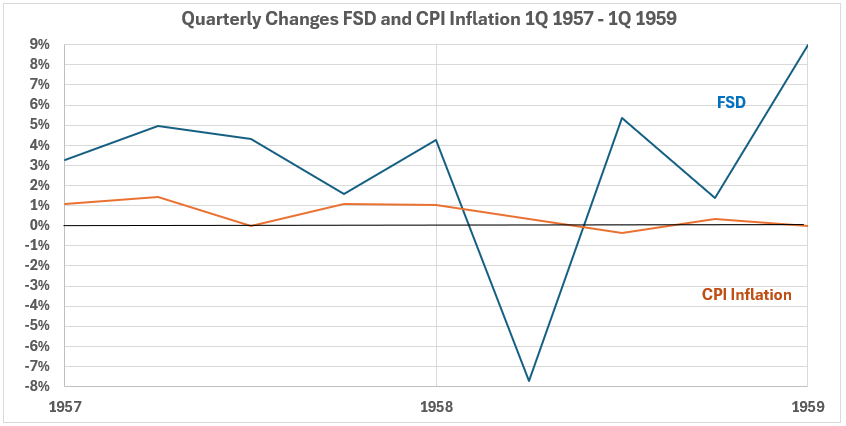

Figure 2. U.S. FSD and Inflation 1Q 1957 – 1Q 1959

During this time period, quarterly changes in CPI inflation are gradually declining. For FSD, quarterly changes are fairly similar in the first four quarters but then reverse to increasingly larger changes in the last four. The first quarter of 1958 saw a large negative change in FSD. The volatility in FSD changes is much larger than for CPI throughout this period.

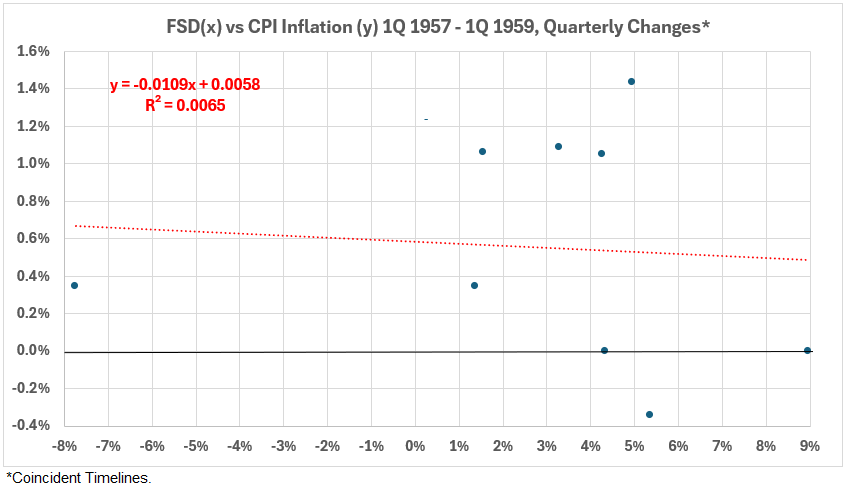

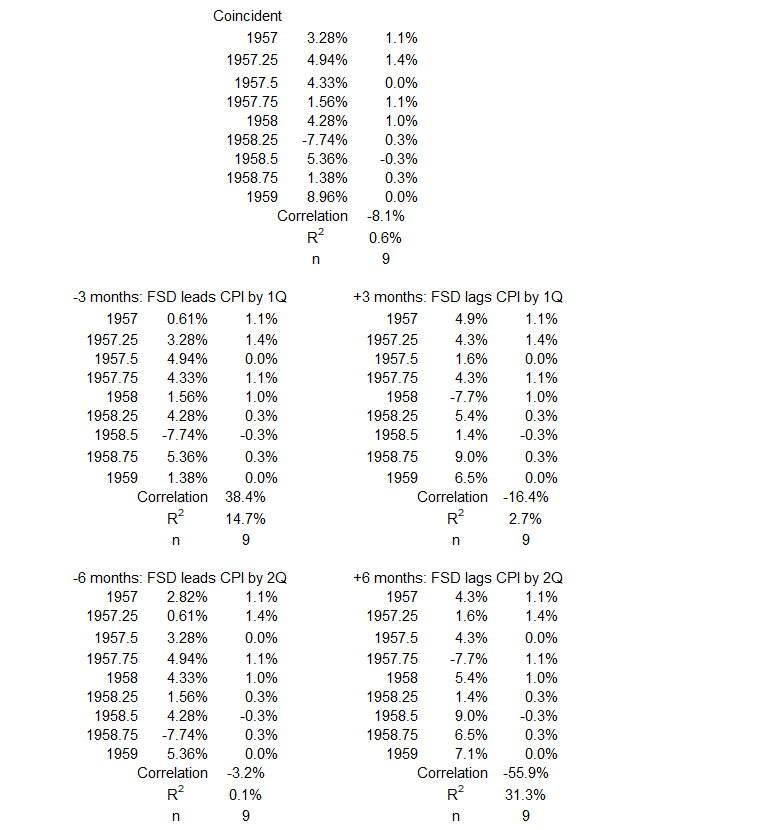

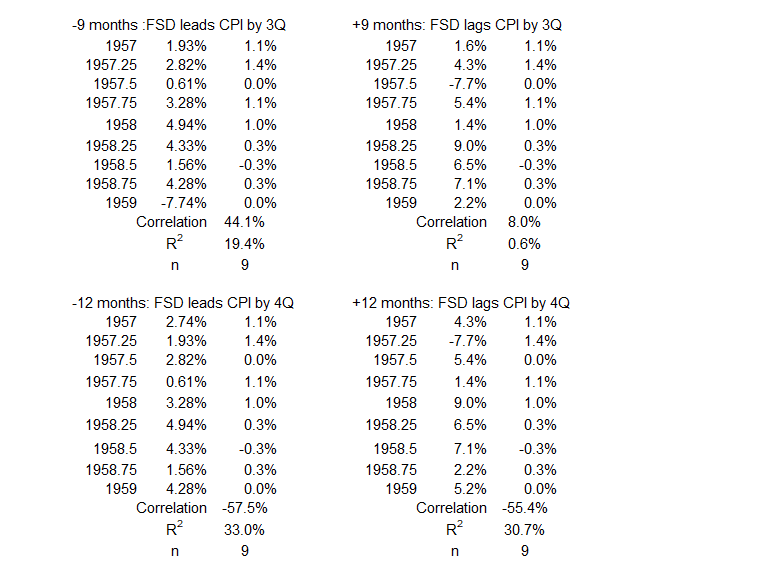

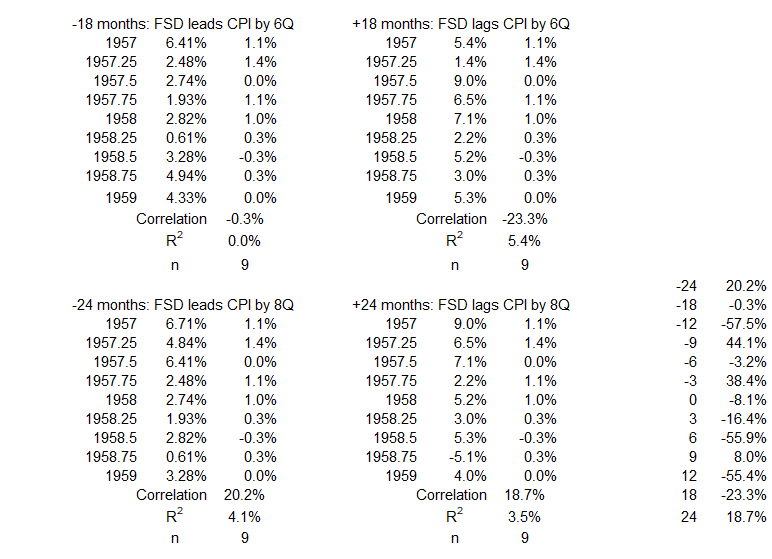

Figure 3. Quarterly Changes in FSD (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 1Q 1957 – 1Q 1959

The association (correlation) between HNO Credit and CPI Inflation is weakly negative for this inflation surge period: R = –8%, R2 = 0.6%. Note that the shape of this scatter plot is not oval (football-shaped). This indicates that the data distribution does not approximate that of a normal distribution. The statistical result for R and R2 may be less meaningful than for a better distribution.4

Figure 4. Correlation Between FSD and CPI Inflation 1Q 1957 – 1Q 1959

Figure 4 shows the positive association of FSD with inflation is moderate only once when debt change comes before inflation (left side of the graph). There is a negative correlation (R = –57%, R2 = 33%) when debt change occurred one year before inflation). All of the other associations on the left side are weak or negligible. This indicates there is little chance that increasing FSD might have caused higher inflation.

On the right side of the graph, we see that the association is moderately negative twice when inflation changes come before debt changes. With 6-month lead time for inflation, R = –56%, R2 = 31% and for a 12-,month lead, R = –55%, R2 = 31%. Changes in inflation might have resulted in up to ~30% of a change in FSD. However, the extent of the cause-and-effect relationships requires additional information.

1Q 1970 – 2Q 1972

Figure 5. U.S. FSD and Inflation 4Q 1969 – 2Q 1972

In this period, inflation and FSD changes are relatively stable in flat trends. However, the volatility of the FSD changes is much greater than for CPI.

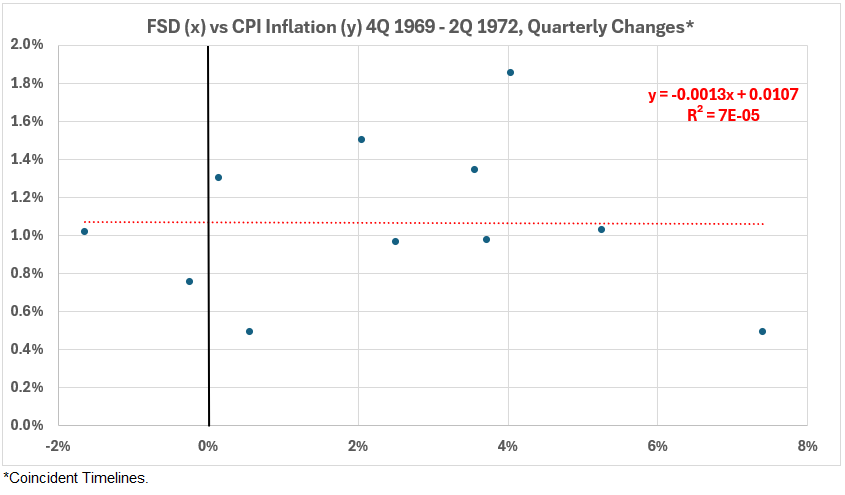

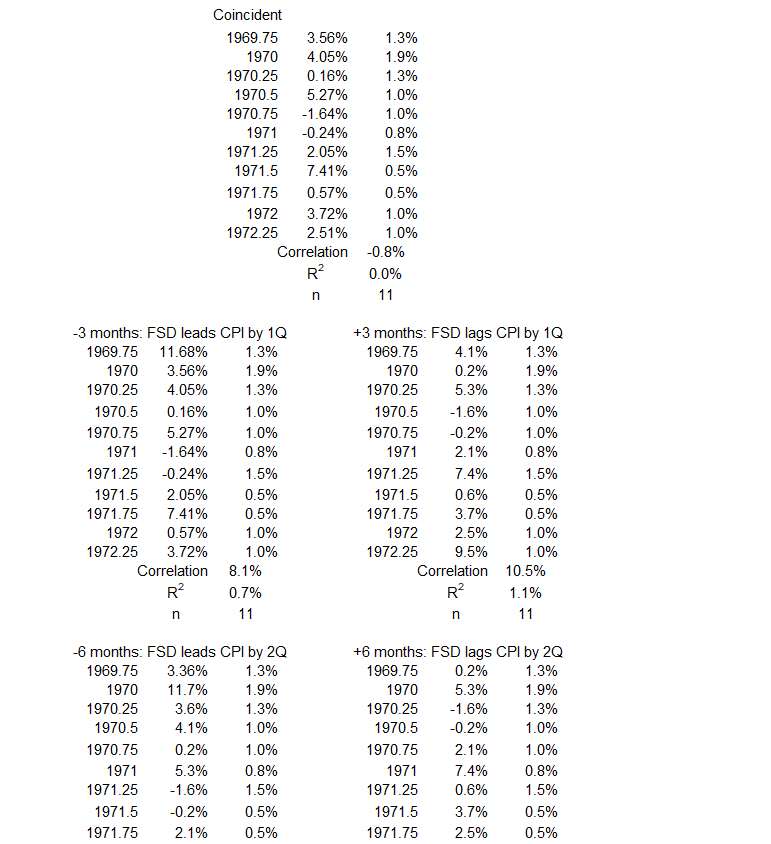

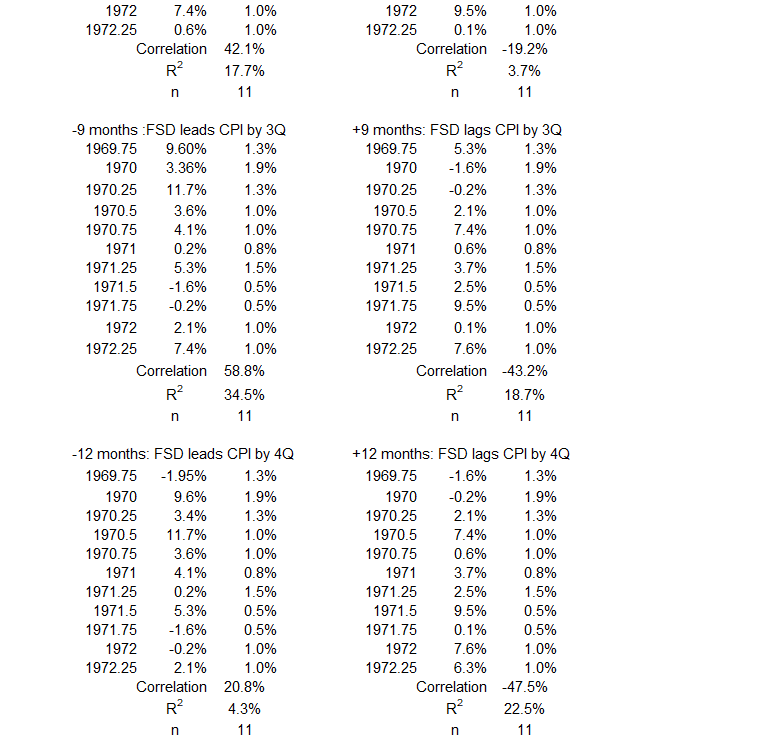

Figure 6. Quarterly Changes in FSD (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 4Q 1969 – 2Q 1972

The association (correlation) between HNO Credit and CPI Inflation is very weakly negative (negligible) during this relatively stable inflation period: R = –0.8%, R2 = 0%.

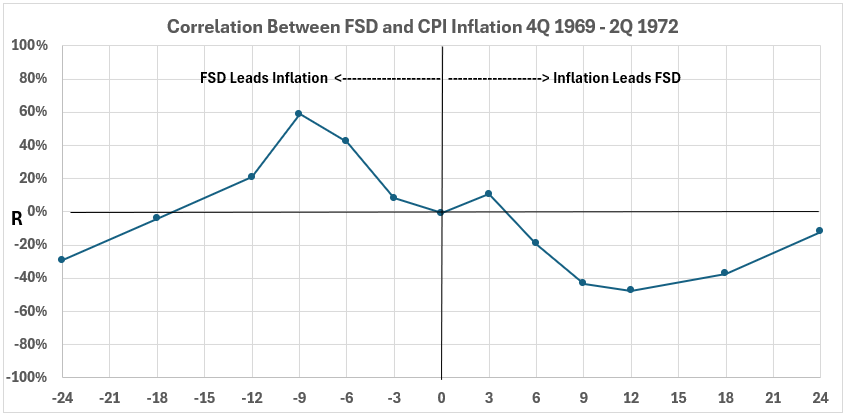

Figure 7. Correlation Between FSD and CPI Inflation 4Q 1969 – 2Q 1972

Figure 7 shows the positive association of FSD changes with inflation is moderate (R = 59%, R2 = 35%) when credit comes before inflation by nine months (left side of the graph). For that point R = 70.7% and R2 = 50%. For all other data points on the left, FSD changes are weakly or negligibly correlated with later inflation changes.

On the right side, the three data points for inflation changes coming 9, 12, and 18 months before FSD changes indicate the possibility that CPI changes might result in FSD changes. The R values are near 40%, and 22%> R2 >14% allow for the possibility that changes in CPI might result in changes in FSD in the opposite. direction. However, causation cannot be confirmed or eliminated without additional information.

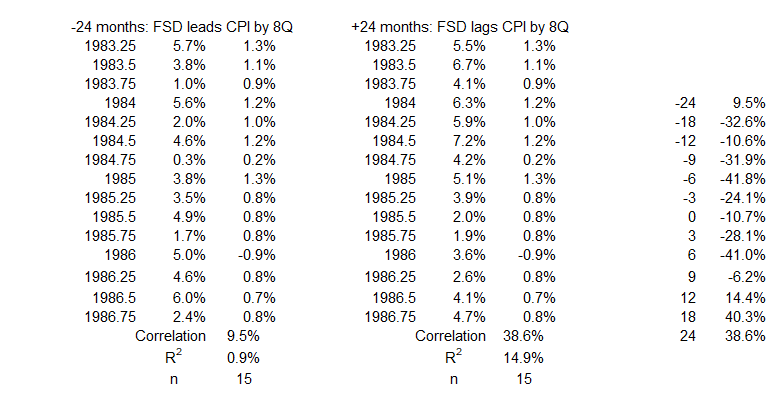

3Q 1983 – 4Q 1986

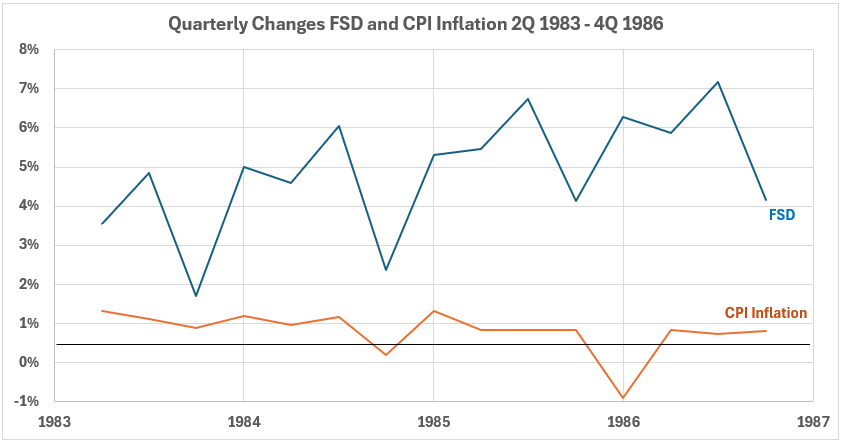

Figure 8. U.S. FSD and Inflation 2Q 1983 – 4Q 1986

Figure 8 shows level trending quarterly changes for CPI, with one deflationary dip for the first quarter of 1986. The quarterly changes for FSD show a gradual uptrend. The much larger volatility for FSD changes has moderated here.

Figure 9. Quarterly Changes in FSD (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 2Q 1983 – 4Q 1986

This period shows a slightly negative correlation: R = –11%, R2 = 1.2% for the coincident timelines data.

Figure 10. Correlation Between FSD and CPI Inflation 3Q 1983 – 4Q 1986

There are weak negative correlations on both sides of the graph, but none are above R = 40% and R2 = 16%. There is little prospect for any significant or moderate cause-and-effect possibilities between the two variables during this time period.

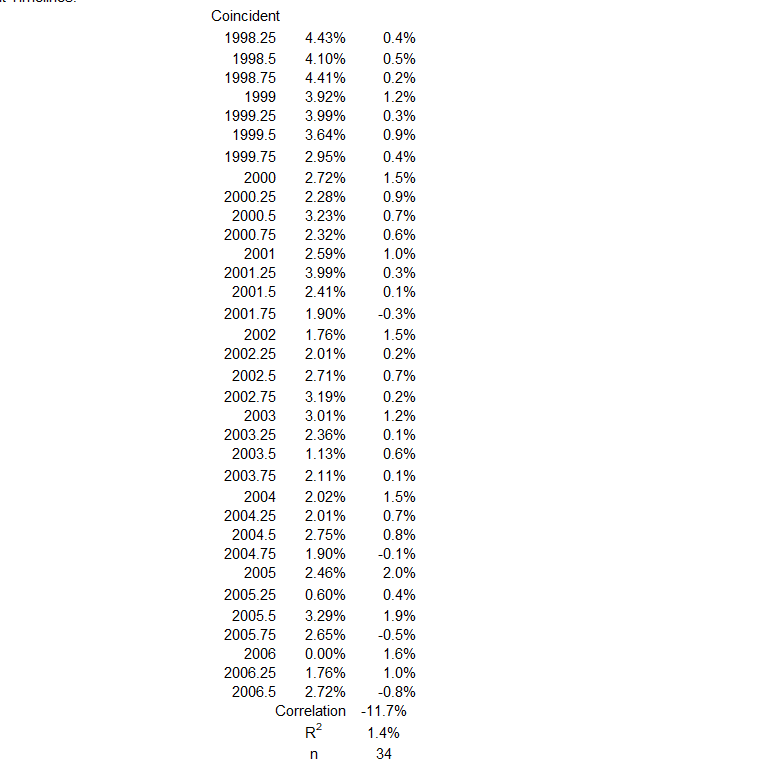

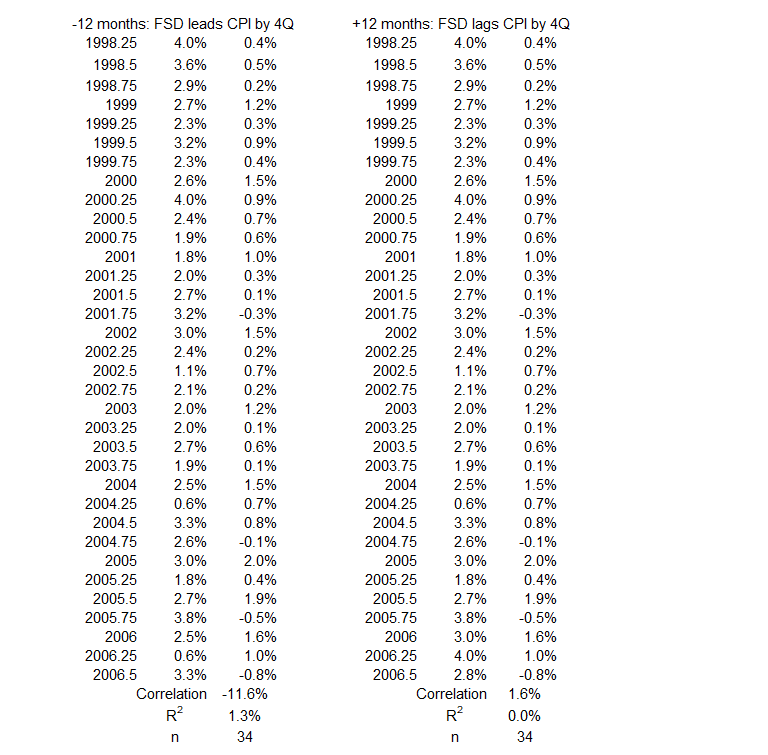

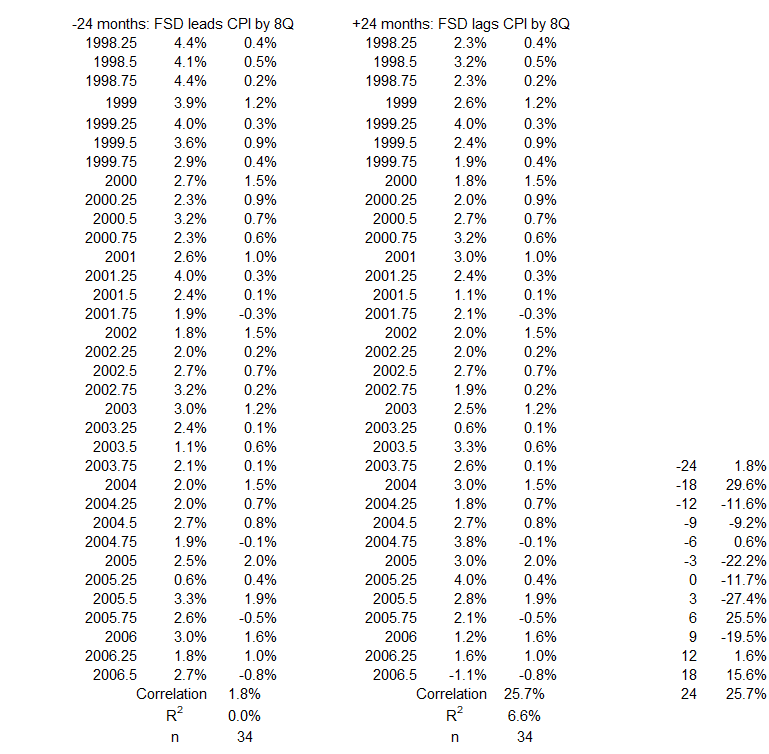

2Q 1998 – 3Q 2006

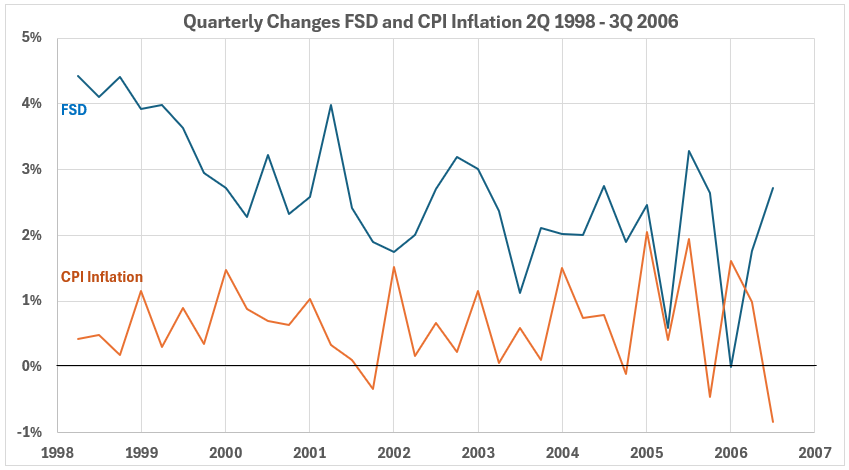

Figure 11. U.S. FSD and Inflation 2Q 1998 – 3Q 2006

Figure 11 shows a different behavior for CPI Inflation than seen in the previous three periods. Although there is a level trend for inflation, there is a little more volatility here.

The data for FSD changes also shows a lower volatility here than previously. Here, the volatility of the two variables is similar. Also, the trend for FSD is toward smaller quarterly changes.

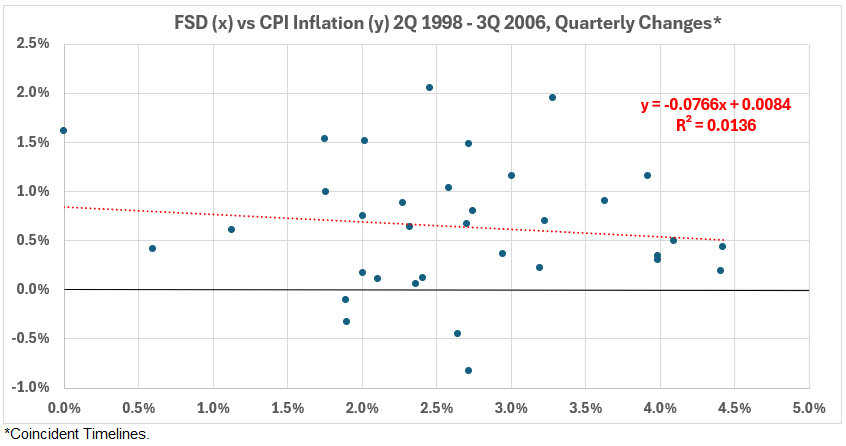

Figure 12. Quarterly Changes in FSD (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 2Q 1998 – 3Q 2006

This data shows a small negative correlation for coincident timelines data: R = –12%, R2 = 1.4%. This association can be considered negligible. It indicates that at least 98.6% of the quarterly variation in FSD is not caused by coincident CPI inflation or vice versa.

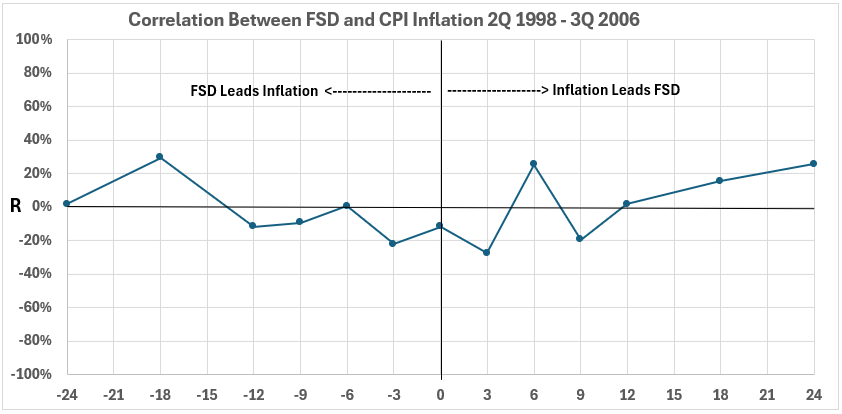

Figure 13. Correlation Between FSD and CPI Inflation 2Q 1998 – 3Q 2006

Figure 13 indicates that there is very little association between FSD and CPI inflation for this 102-month period. The highest value of R is 29.6% for any of the data pairs. That produces an R2 = 8.4%, the maximum amount of change in one variable possibly caused by a change in the other. In other words, more than 91% of the change in either of these variables has to be caused by something besides the other variable during this period.

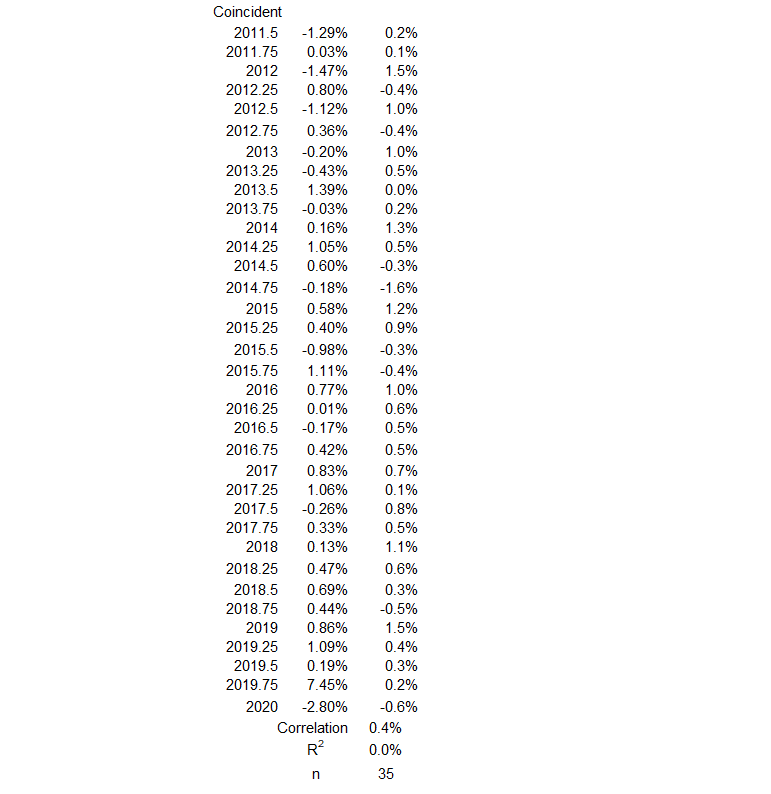

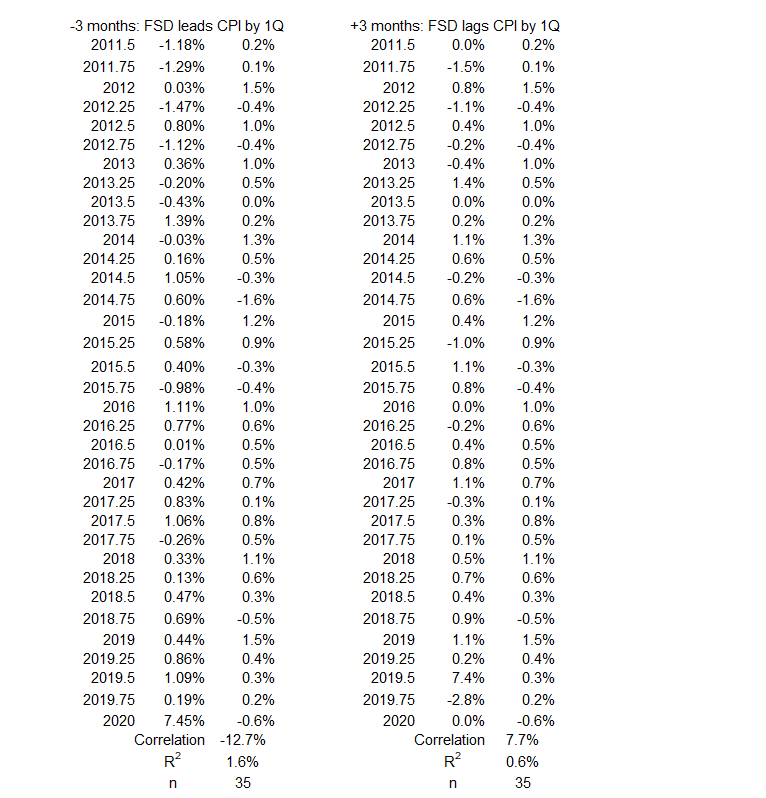

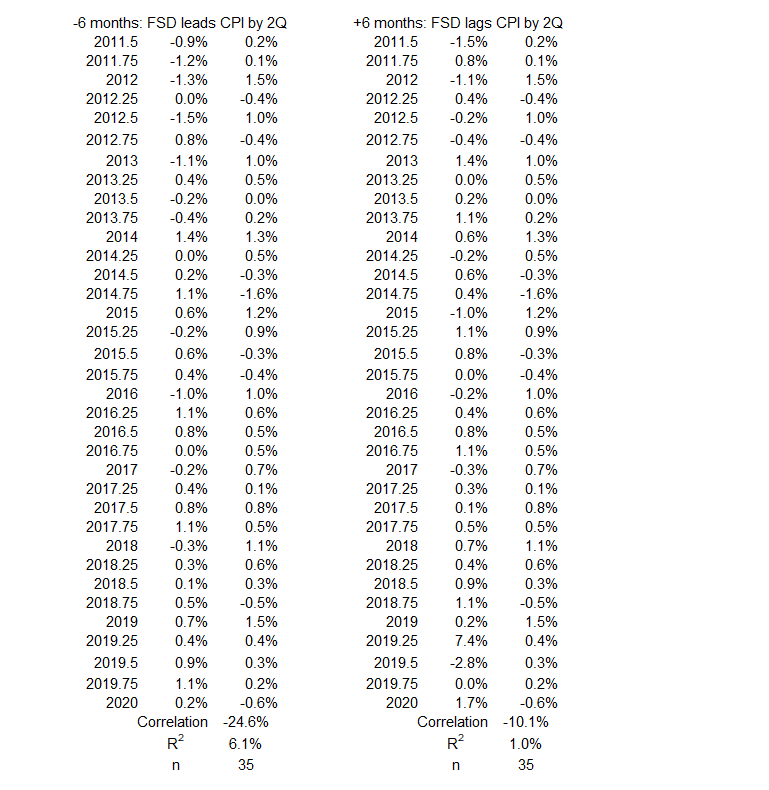

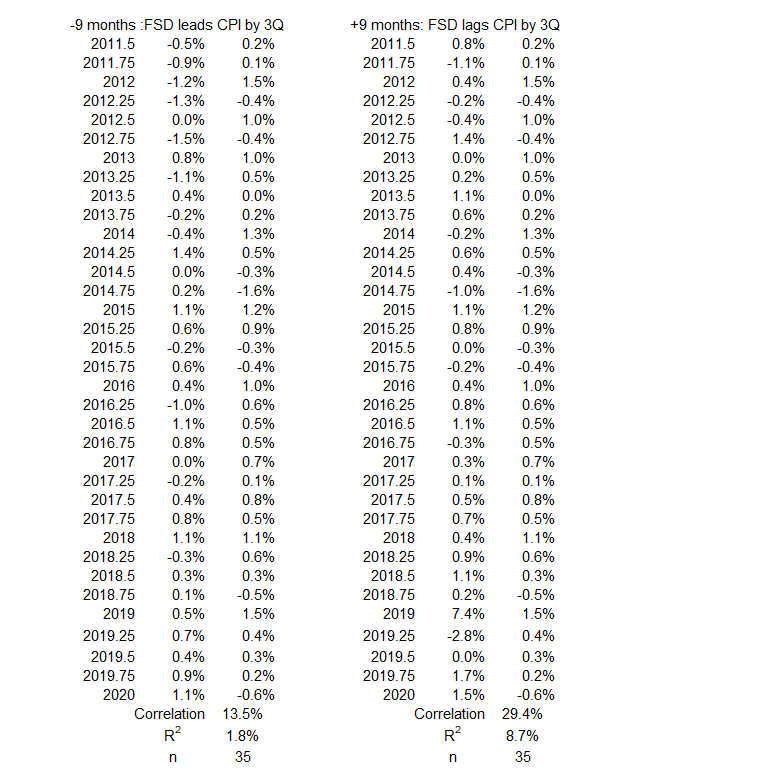

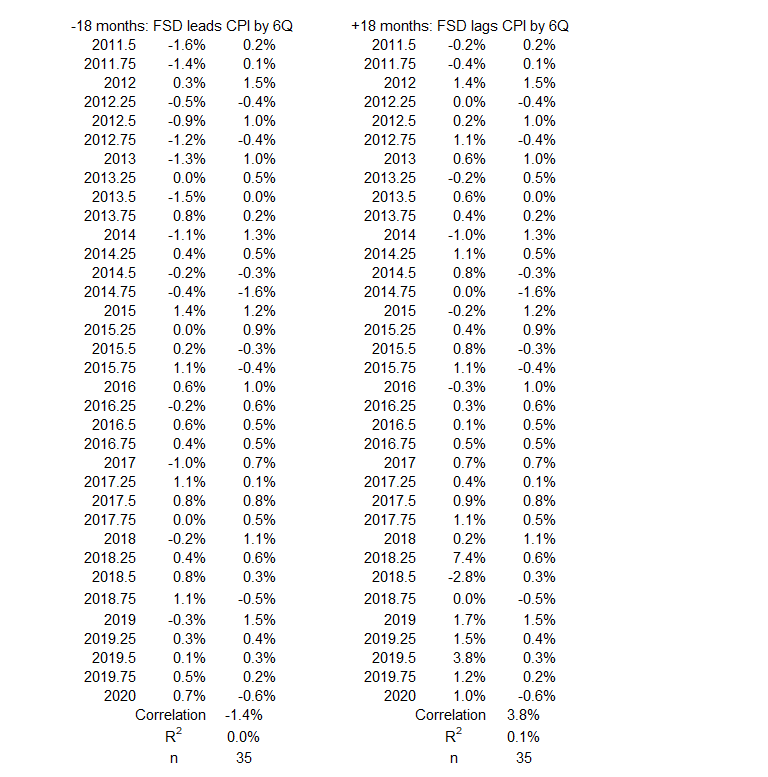

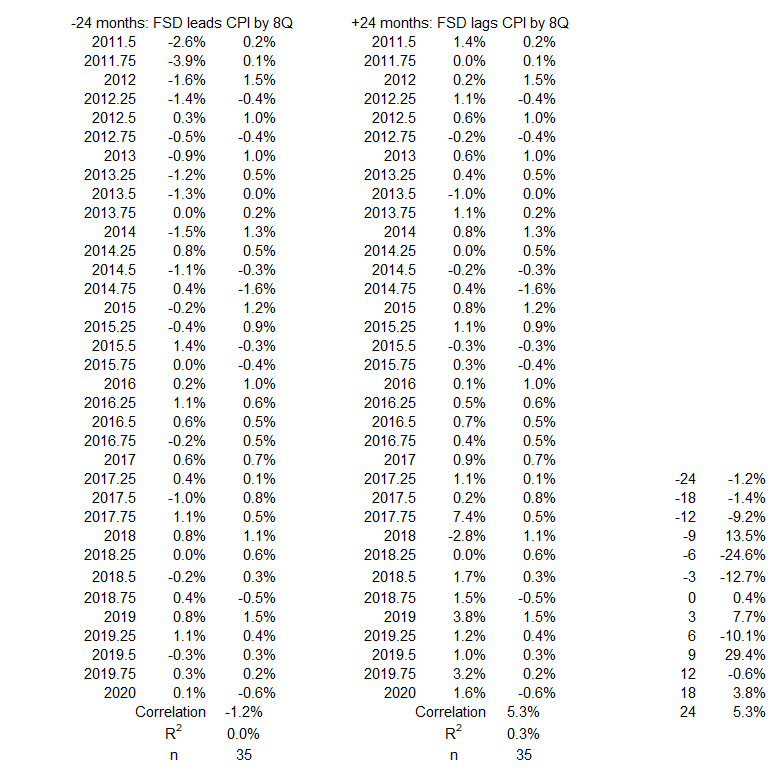

3Q 2011 – 1Q 2020

Figure 14. U.S. FSD and Inflation 3Q 2011 – 1Q 2020

Figure 14 shows quarterly CPI inflation and NFC credit changes both in generally level trends. The remarkable points in this graph are three:

- There are seven deflationary quarters.

- There is one quarterly contraction in FSD.

- There are two noteworthy spikes in FSD – in the first quarter of 2018 and especially in the third quarter of 2020.

Figure 15. Quarterly Changes in FSD (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 3Q 2011 – 1Q 2020

The coincident timeline data show a negligible positive correlation in this time period: R = 0.4%, R2 = 0%.

Figure 16. Correlation Between FSD and CPI Inflation 3Q 2011 – 1Q 2020

Figure 16 is similar to Figure 13. There is no opportunity for either variable to have possibly caused a significant or moderate change in the other.

Conclusion

The conclusion is divided into two sections. First, the analysis results are discussed for the current study of time periods without significant inflation surges up or down. Then, there is an overall summary of associations between FSD and CPI for inflation/disinflation periods and a look forward to future work.

Patterns of Correlation for Periods without Significant Inflation Surges

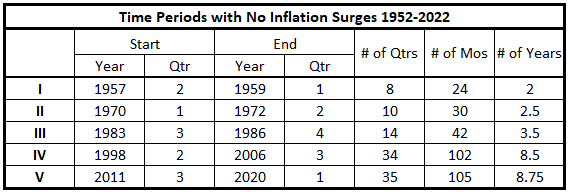

To simplify this discussion, the five periods without significant surges in inflation are numbered, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Time Periods with No Inflation/Disinflation Surges 1952-1022

There are fewer correlations found in this data than those for other money growth change sources. The general observations for the five periods analyzed in this article are:

- Inflation volatility quarter-to-quarter is less for I, II, and III compared to IV and V.

- There are two periods (I and II) when the positive association between FSD changes and subsequent inflation changes is moderate.

- Three periods (I, II, and III) weakly or moderately correlate negatively for inflation changes and subsequent FSD changes.

- Two periods (IV and V) show limited or negligible positive and negative correlations for all timeline offsets.

Overview of All Financial Sector Debt Spending Data Sets

Let’s review the results for all 18 time periods – positive and negative inflation surges plus the periods without surges analyzed above. We use the letter designations in Table 1 and the numerical designations in Table 2 to simplify the discussion.

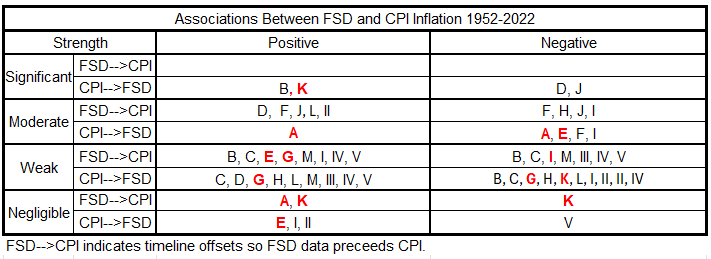

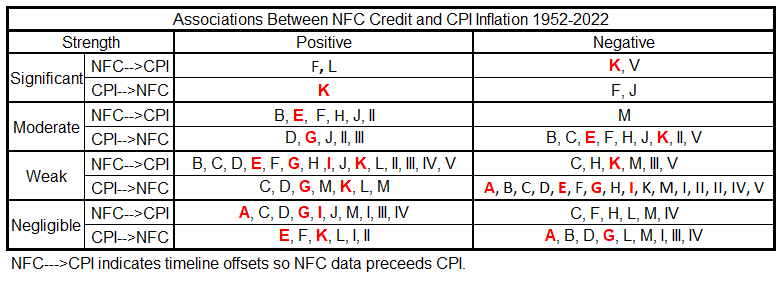

Table 3 summarizes the results for all time periods for correlation (association) of quarterly FSD changes with CPI Inflation changes. In the table, black letters are for periods with positive inflation surges, red letters are for periods with negative inflation surges, and Roman numerals are for periods without surges.

Table 3. Associations Between FSD and CPI Inflation 1952-2022

The associations shown in Table 3 indicate the maximum possible cause-and-effect relationships. The moderate correlation strength covers the range 50%>R2>25%. So, for example, R2 = 40%, no more than 40% of one variable can result from the other. However, the lower limit of cause-and-effect is zero, depending on other information in addition to the statistical result. As stated differently, the cause of one variable is between 60% and 100%, based on factors other than the second variable.

The weak and negligible associations give a more satisfying result. They indicate that much (more than 75%) of the cause of one variable comes from other sources than the second (weak association), or nearly 100% comes from other sources (negligible).

There are a few possibilities for more than 50% cause-and-effect (significant strength), but the proof is not given without further information.

There are also possibilities for important cause-and-effect relationships between 25% and 50% (moderate strength). However, additional information is needed in each case to prove that the causations are not lower than R2 would indicate.

The most remarkable feature of Table 3 is that the number of events in the weak and negligible classes is much greater than in the moderate and significant classes. This is more pronounced than for the other sources of money we have studied.

Summary

Next, we will return to update the Federal Deficit Spending and Inflation analysis.

Appendix

Below are the data sets for each period without surging inflation or disinflation/deflation. They come from the tables of timeline alignments3 (Financial Sector Debt and Inflation: Part 1).

2Q 1957 – 1Q 1959

1Q 1970 – 2Q 1972

3Q 1983 – 4Q 1986

2Q 1998 – 3Q 2006

3Q 2011 – 1Q 2020

Footnotes

1. Lounsbury, John, “Financial Sector Debt and Inflation: Part 2”, EconCurrents, March 17, 2024. https://econcurrents.com/2024/03/17/financial-sector-debt-and-inflation-part-2/.

2. Lounsbury, John, “Financial Sector Debt and Inflation: Part 3”, EconCurrents, March 24, 2024. https://econcurrents.com/2024/03/24/financial-sector-debt-and-inflation-part-3/.

3. Lounsbury, John, “Financial Sector Debt and Inflation: Part 1”, EconCurrents, March 10, 2024. https://econcurrents.com/2024/03/10/financial-sector-debt-and-inflation-part-1/.

4. Freedman, David, Pisani, Robert, and Purves, Richard, Statistics, Fourth Edition, W.W. Norton & Company (New York) and Viva Books (New Delhi), 2009. See Chapters 8 & 9 for an explanation of how normal distributions relate to determining correlation coefficients. See p. 147 for a discussion of football-shaped scatter diagrams.

5. Lounsbury, John, “Government Spending and Inflation: Reprise and Summary”, EconCurrents, August 20, 2023. https://econcurrents.com/2023/08/20/government-spending-and-inflation-reprise-and-summary/.