The full data sets for the 71 years from 1952 to 2022 show no discernable association patterns (correlations) for nonfinancial credit growth and inflation changes.1 Thus, we started an analysis by looking specifically at the various regimes of inflation change during the 71-year timeline. The most recent post2 analyzed the eight time periods over 71 years with positive inflation surges. This article analyzes the five periods for 1952-2022 with negative inflation (disinflation/deflation) surges.

Photo by Dennis Siqueira on Unsplash.

Introduction

The 71 years from 1952 to 2022 are divided into three types of inflationary behavior:1

- Significant inflation increases;

- Significant inflation decreases;

- No significant inflation changes.

An inflation change is significant if it is ≥4.0% with no intervening countertrend change >1.5%.

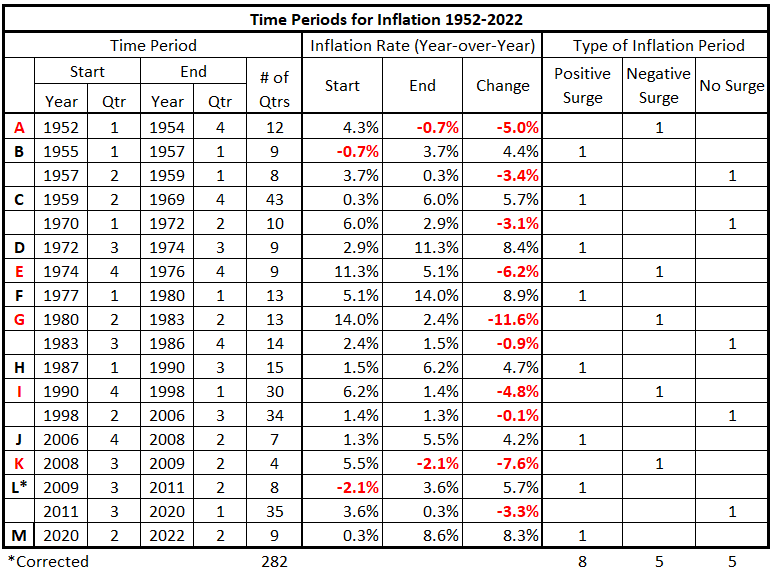

Previously, we defined the partitioning of inflation into the pattern in Table 1.

Table 1. Timeline of Inflation Data 1952-2022 (Previously Table 4*.1)

We will examine each category of inflation behavior separately. In this piece, we analyze the significantly negative periods of inflation (disinflation and deflation surges).

Data

The data is from Tables 5-17, prepared previously.1

There are 13 quarterly timeline alignments:

- HNO Credit and CPI Inflation quarters are coincident.

- HNO Credit leads and lags CPI Inflation by one quarter (±3 months)

- HNO Credit leads and lags CPI Inflation by two quarters (±6 months)

- HNO Credit leads and lags CPI Inflation by three quarters (±9 months)

- HNO Credit leads and lags CPI Inflation by four quarters (±12 months)

- HNO Credit leads and lags CPI Inflation by six quarters (±18 months)

- HNO Credit leads and lags CPI Inflation by eight quarters (±24 months)

Analysis

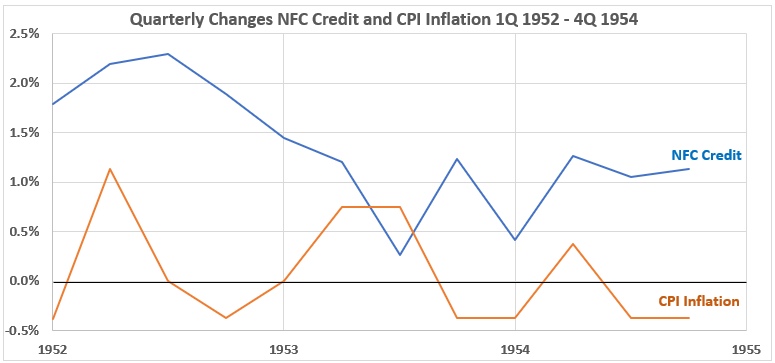

1Q 1952 – 4Q 1954

Figure 1. U.S. FNC Credit and Inflation 1Q 1952 – 4Q 1954

The trends for nonfinancial corporate (NFC) credit and inflation changes are down after initial upticks. There are no negative changes for NFC, but inflation declined in five of the ten quarters.

Figure 2. Quarterly Changes in NFC Credit (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 1Q 1952 – 4Q 1954

The association between the two variables is negligible. R = 5.6% and R2 = 0.3%. (Note: the value for R2 provided by Excel does not agree with the value I have calculated directly from the data. I cannot explain how the Excel values were determined, so I have used the values for R and R2 that I calculated directly.

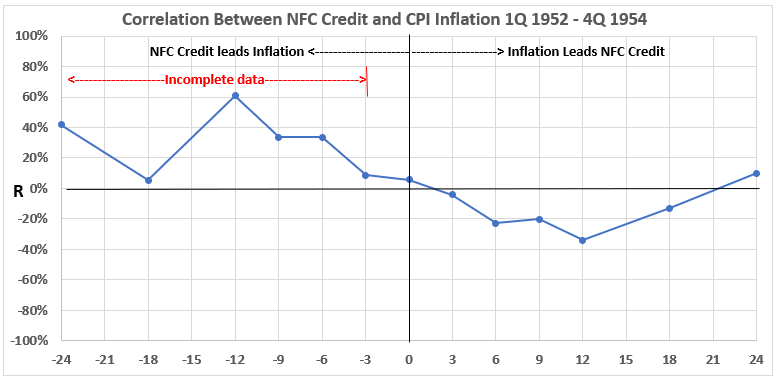

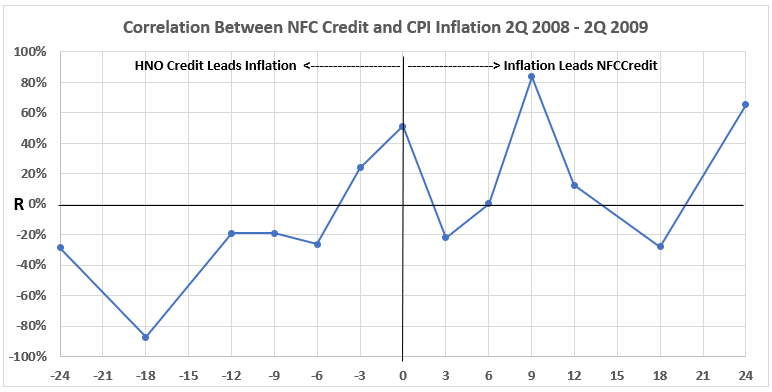

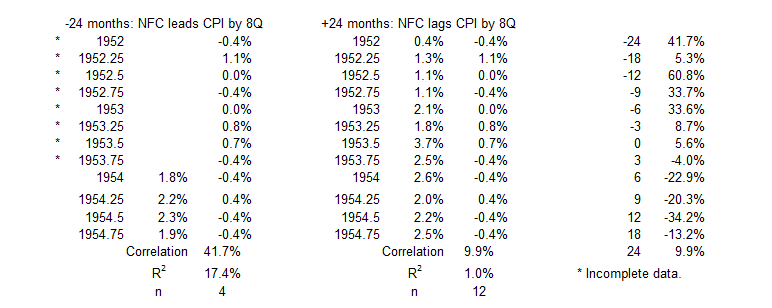

Figure 3. Correlation Between NFC Credit and CPI Inflation 1Q 1952 – 4Q 1954

As the timelines shift relative to each other, the association (correlation) is small, both negative and positive, for coincident data and NFC Credit following inflation by the number of months indicated. The largest association is negative, with inflation occurring 12 months before NFC credit. This does not indicate much possibility for cause and effect, R= 34.2% and R2 = 11.7%. There is no data for NFC before 1952 in this dataset, so the left-hand side of the graph for NFC credit occurring before CPI inflation is constructed with incomplete data and should not be included in any analysis.

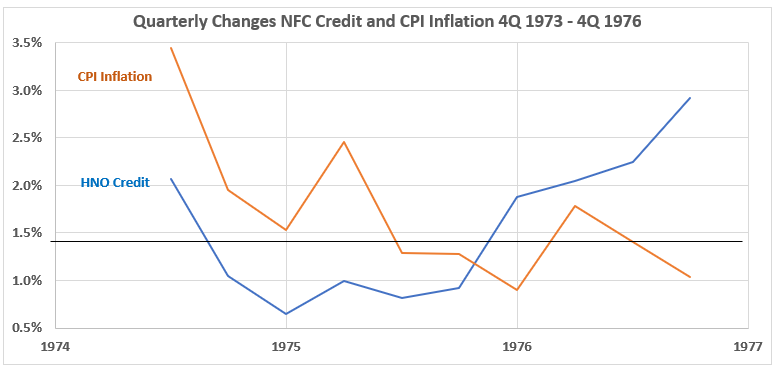

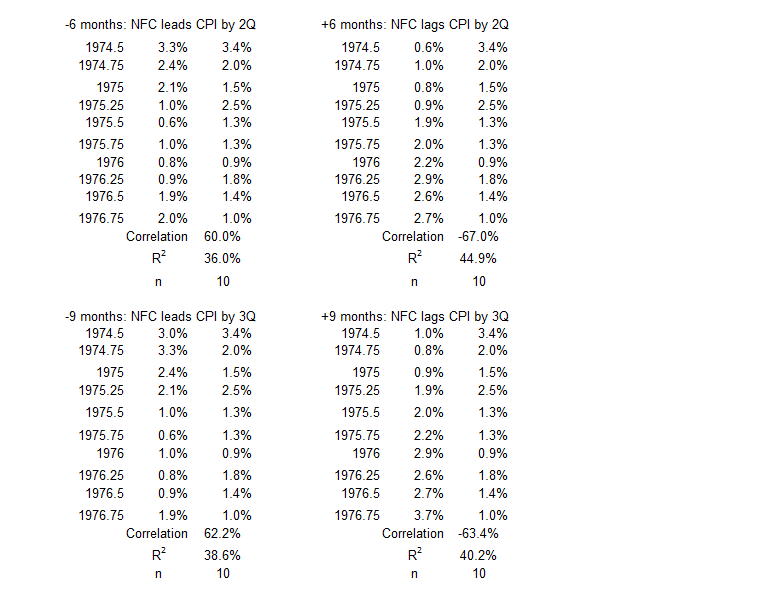

4Q 1974 -4Q 1976

Figure 4. U.S. NFC Credit and Inflation 4Q 1974 – 4Q 1976

NFC credit changes and inflation declined at the beginning of this period. But then the trend for NFC quarterly changes increased while inflation changes continued to get smaller.

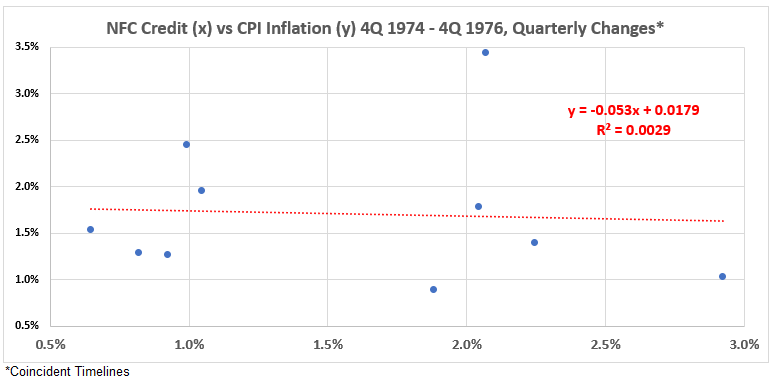

Figure 5. Quarterly Changes in NFC Credit (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 4Q 1974 – 4Q 1976

When the data timelines coincide, the overall association between these two variables is negligible. R = –5.3% and R2 = 0.3%.

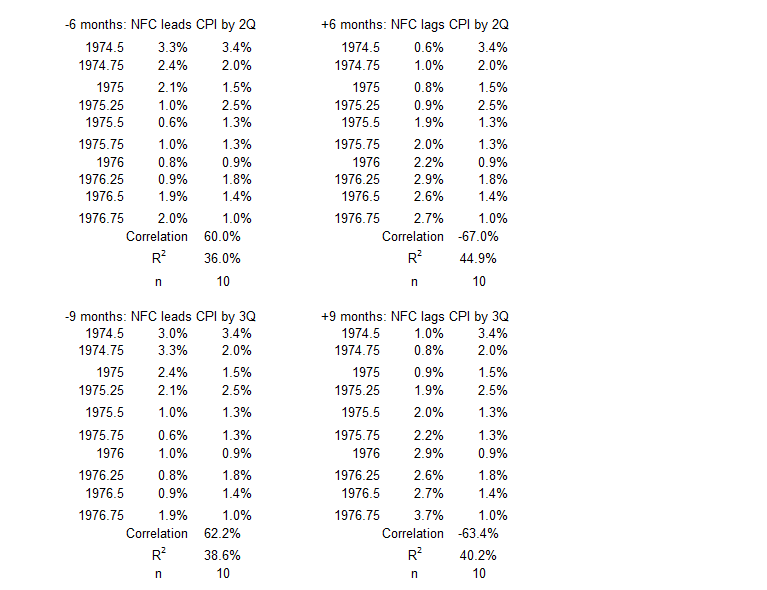

Figure 6. Correlation Between NFC Credit and CPI Inflation 4Q 1974 – 4Q 1976

Figure 6 has a clear message. The positive association of NFC Credit with inflation is moderate when credit comes before inflation. On the other hand, the association is negative (again, moderately and strongly) when inflation comes before credit spending.

Let’s restate the observations, with an emphasis on the fact that inflation is declining significantly during this time period.

From the left-hand side of Figure 6, this data indicates that decreasing NFC Credit spending changes are moderately positively associated with declining inflation six to twelve months in the future. R2 values are 36%, 39%, and 47%. The inference is that if there is cause-and-effect, it takes some time for lower credit spending to have an effect on inflation.

From the right-hand side of Figure 6, we see a consistent moderate negative association between the variables. R2 values for six, nine, and twelve months are 40%, 45%, and 49%. This implies that either:

- There is no association between falling inflation and reduced use of consumer credit; or

- It is possible that falling inflation could lead to increased use of consumer credit.

This is a good time to remind ourselves that association only means cause-and-effect might be possible. Other information is needed to determine if there is any causation at all.

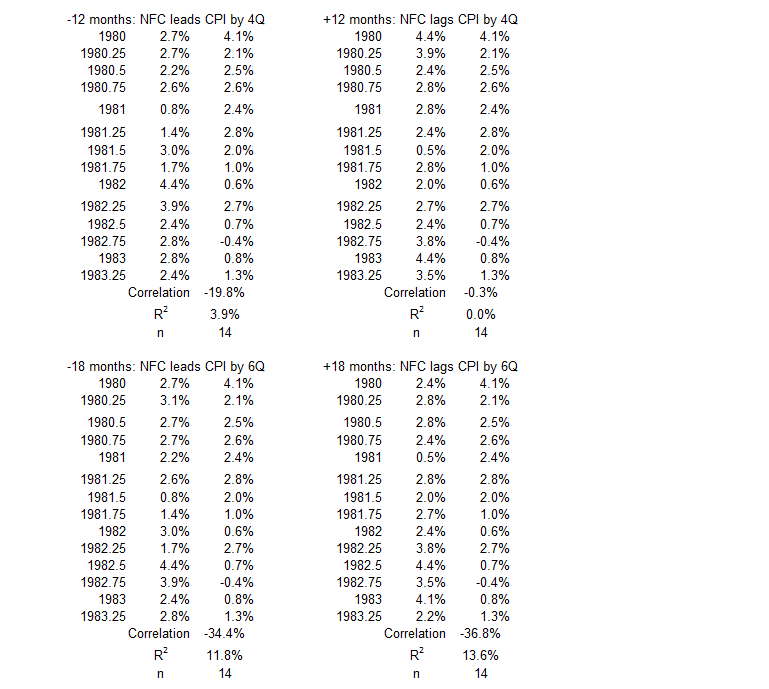

2Q 1980 – 2Q 1983

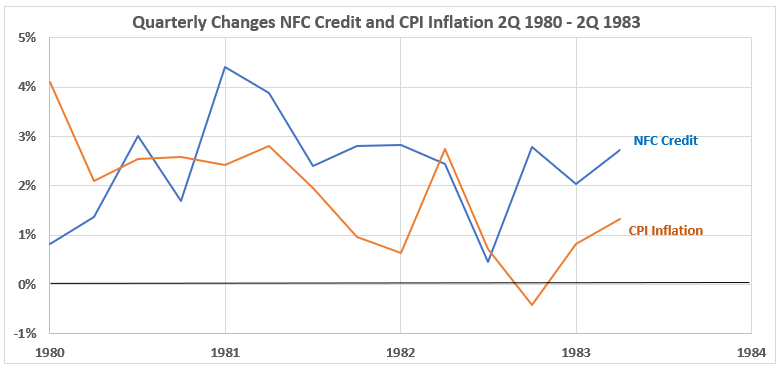

Figure 7. U.S. NFC Credit and Inflation 2Q 1980 – 2Q 1983

The trends for NFC Credit changes (initially up and then down) differ from the CPI Inflation changes trend, which is generally down throughout the period.

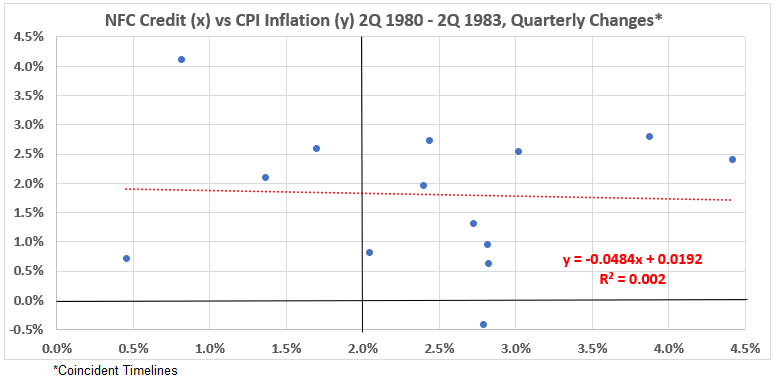

Figure 8. Quarterly Changes in NFC Credit (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 2Q 1980 – 2Q 1983

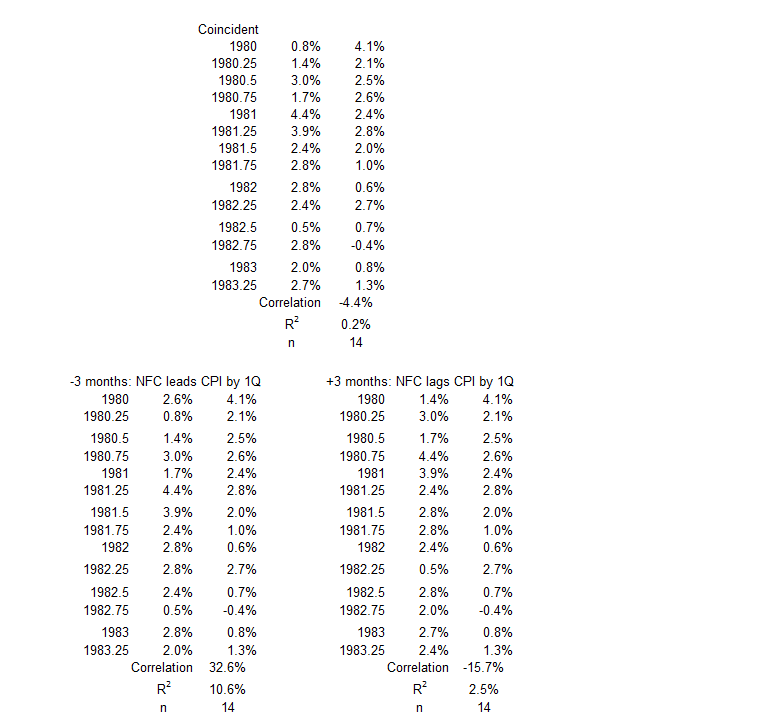

The correlation when the two data timelines coincide is negligible. R = –4.4% and R2 = 0.2%.

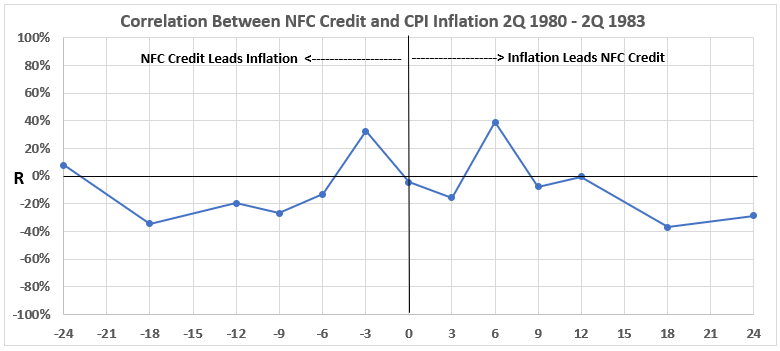

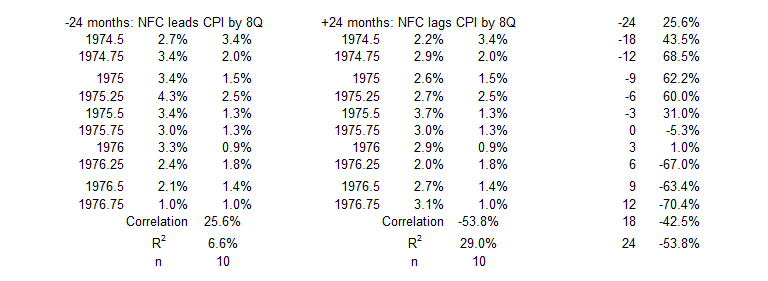

Figure 9. Correlation Between NFC Credit and CPI Inflation 2Q 1980 – 2Q 1983

There is limited possibility for cause-and-effect relationships during this period. The highest positive association is for inflation change coming six months before NFC change is measured, R = 38.9%, R2 = 15%. The largest negative association (NFC change 18 months before inflation change) is R = –34.4%, R2 = 12%.

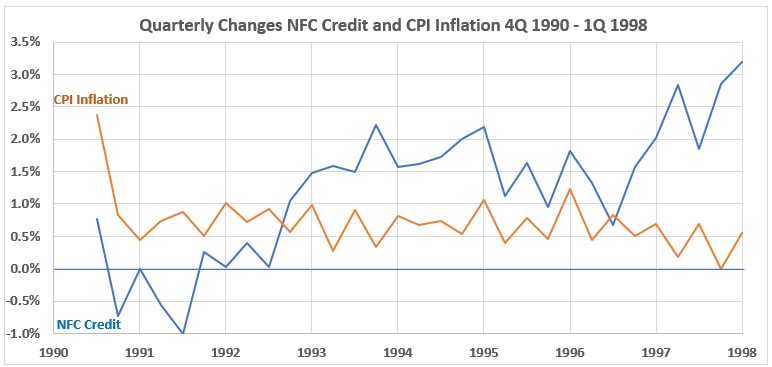

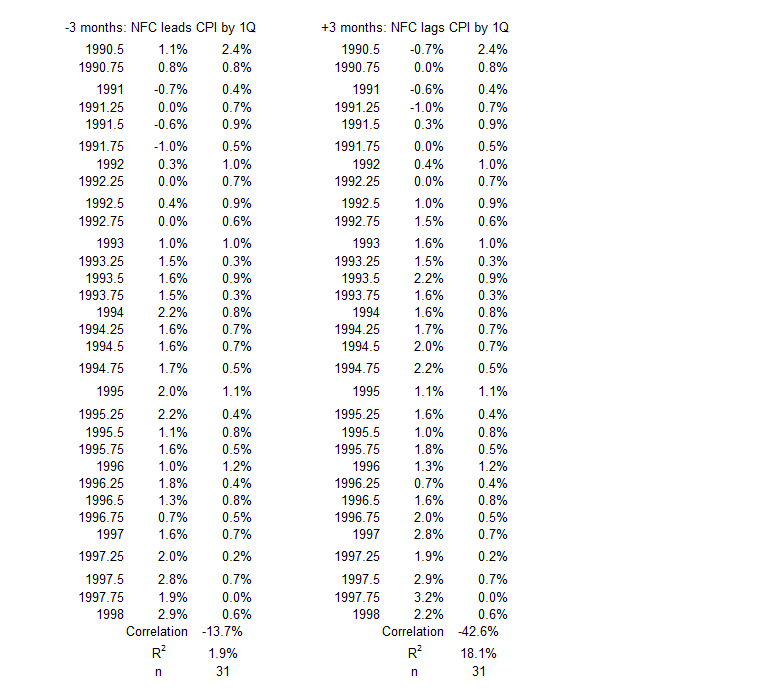

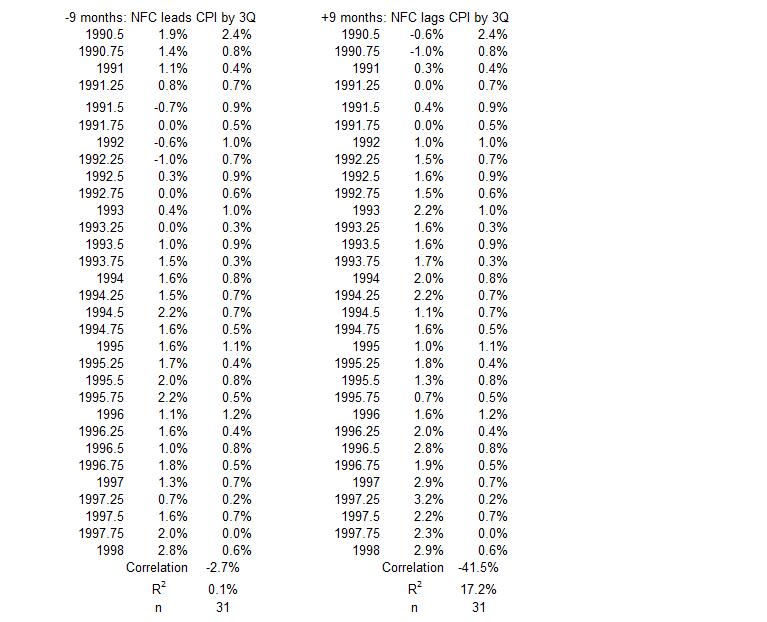

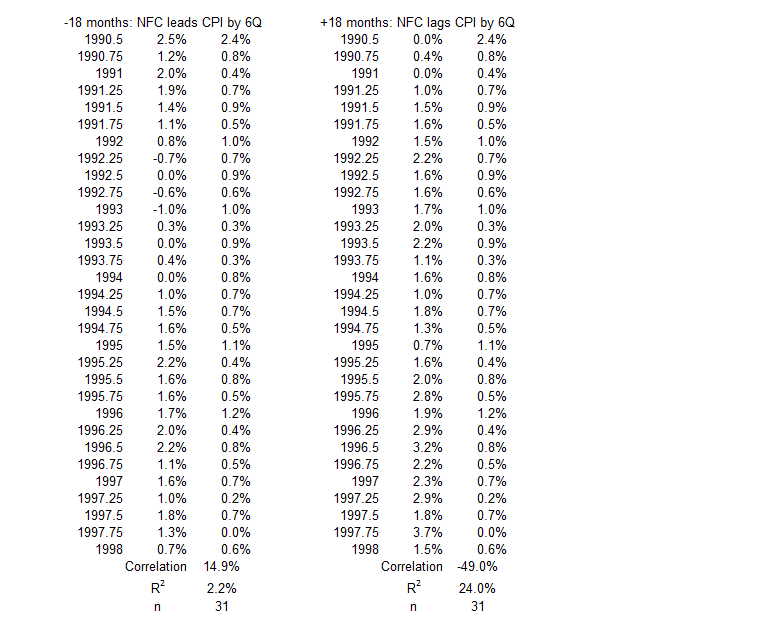

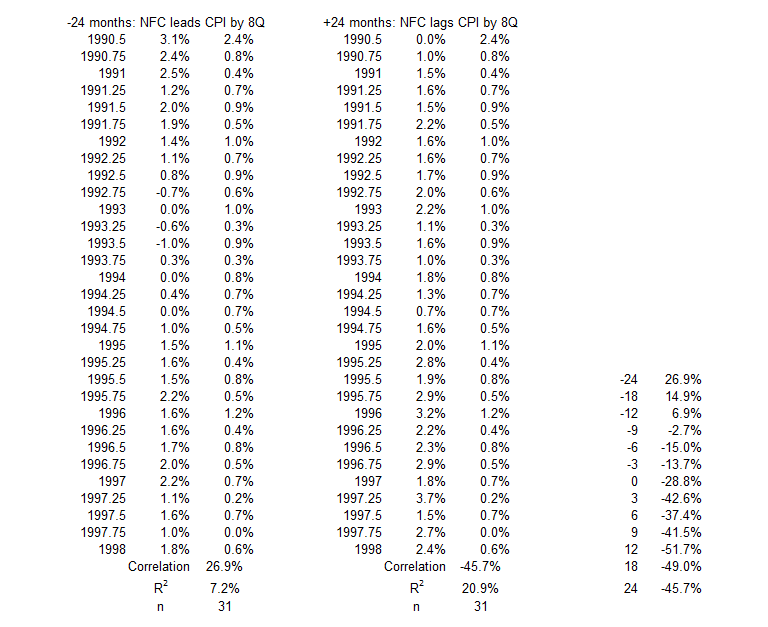

4Q 1990 – 1Q 1998

Figure 10. U.S. NFC Credit and Inflation 4Q 1990 – 1Q 1998

After the first quarter, the trend for NFC credit changes generally increased with a flat-to-down period from the middle of 1993 to the middle of 1996. Note the unusual negative quarters for NFC credit changes from 4Q 1990 through 2Q 1991. Inflation change also had a big drop for the opening quarter. Then, the changes were quite level until there was a declining trend for 1997. There is not much visual evidence of correlation here.

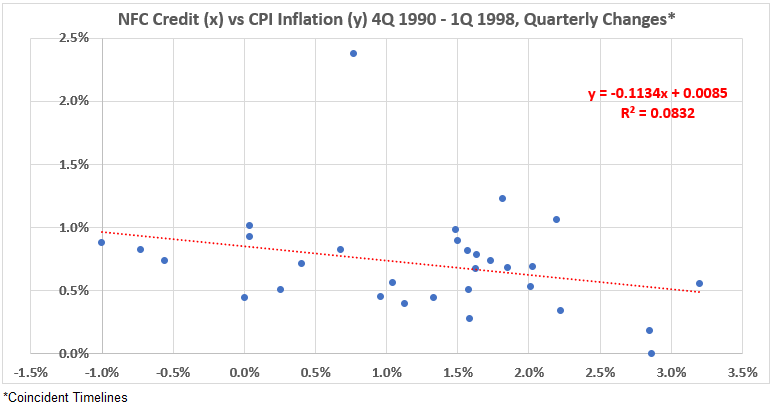

Figure 11. Quarterly Changes in NFC Credit (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 4Q 1990 – 1Q 1998

The scatter plot (Figure 11) confirms the general observation made for Figure 10: There is a limited negative association between coincident credit spending and inflation during the 1990s. R = –29% and R2 = 8.3%.

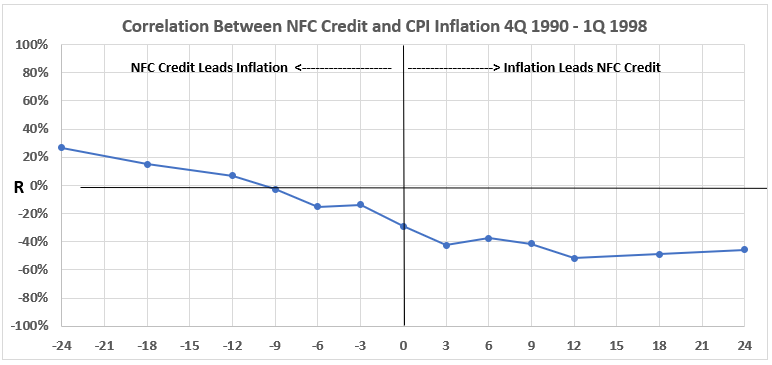

Figure 12. Correlation Between NFC Credit and CPI Inflation 4Q 1990 – 1Q 1998

Figure 12 shows little opportunity for major cause-and-effect relationships when NFC credit changes come before inflation (left-hand side of the graph). There are weak negative correlations on the right-hand side, with one moderate association for inflation change twelve months before NFC credit change (R = –51.7% and R2 = 27%). There are five data points near, at, or slightly above R = 40%. The R2 values range from 14% to 24% for those five points. Because there are so many data points in a narrow range, we should not dismiss the possibility that up to 27% of the increase in the size of quarterly changes could be caused by the decreasing six of inflation changes during the 1990s.

Caveat: Possibility does not prove anything. Additional information is needed for cause-and-effect proof.

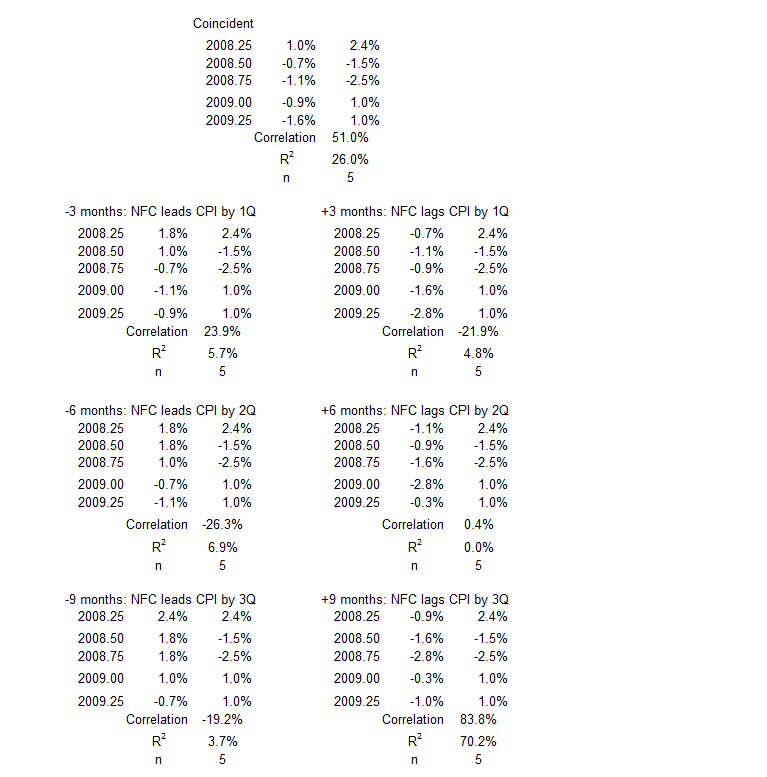

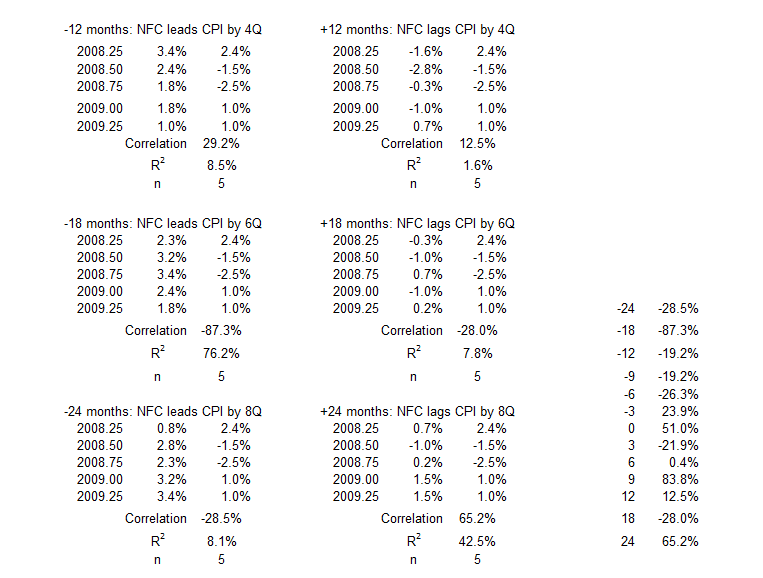

3Q 2008 – 2Q 2009

Figure 13. U.S. NFC Credit and Inflation 3Q 2008 – 2Q 2009

In Figure 13, we see a data set that is different from the first four we analyzed. CPI Inflation changes have a “wild” pattern, while NFC credit changes show a smooth decline from slightly positive to modestly negative.

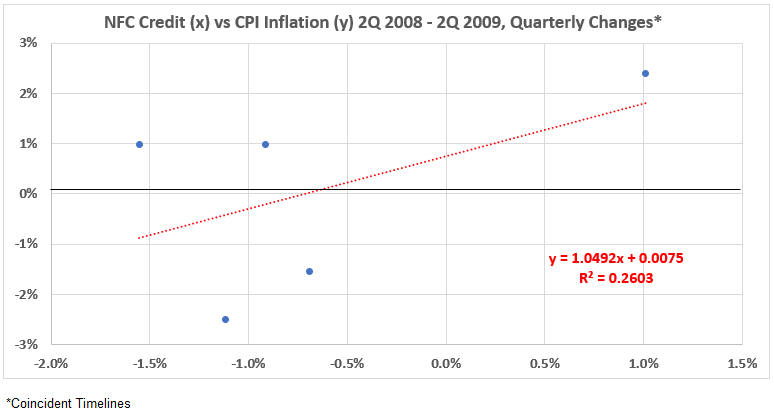

Figure 14. Quarterly Changes in NFC Credit (x) vs. CPI Inflation (y) 3Q 2008 – 2Q 2009

There is a lot of scatter in Figure 14, suggesting that analysis of this small data set may offer some problems. For a discussion, see this.3 The association here is moderate and positive. R = 51% and R2 = 26%. The correlation shown in Figure 14 is entirely dominated by one data point in the upper right. The data for a scatter diagram of the other four points produces y = -3.295x – 0.0271, R = –78%, and R2 = 61%.

Figure 15. Correlation Between NFC Credit and CPI Inflation 3Q 2008 – 2Q 2009

The very small data sample makes extracting any meaning from Figure 15 impossible.

Conclusion

Only one period of declining inflation showed the possibility of cause-and-effect relationships of moderate (>25%) extent. The 1974-76 deflationary period showed two moderate causation possibilities:

- Up to 47% of inflation increases might have resulted from NFC credit increases.

- Up to 49% of NFC credit increases might have resulted from inflation decreases.

After analyzing periods with no significant inflation changes, there will be more discussion of the results. That comes next week.

Appendix

The data sets for each significant negative inflation (disinflation and deflation) period are below. They come from the tables of timeline aligments1 (Nonfinancial Corporate Credit and Inflation: Part 1).

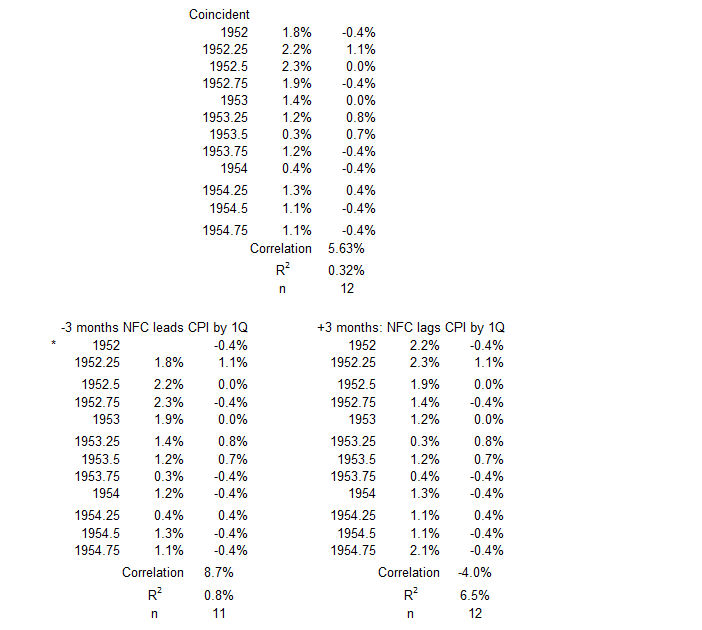

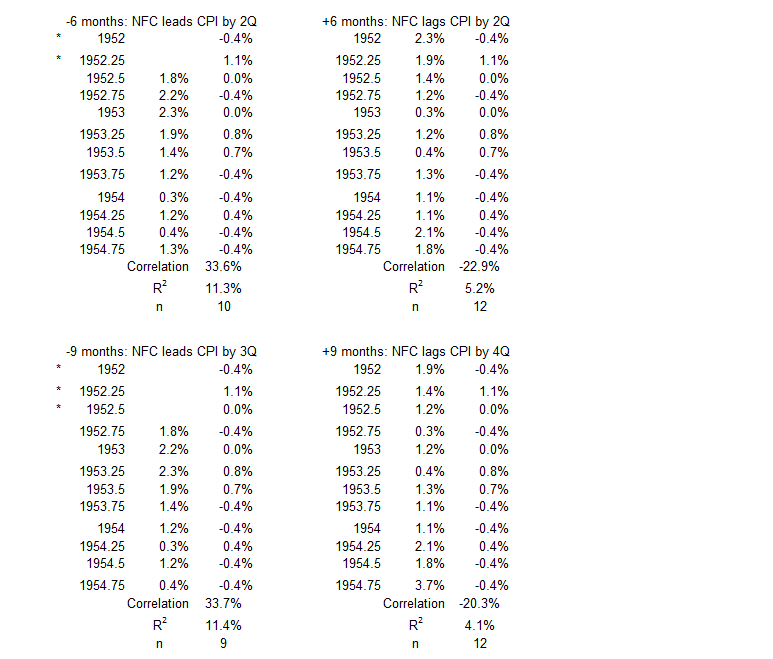

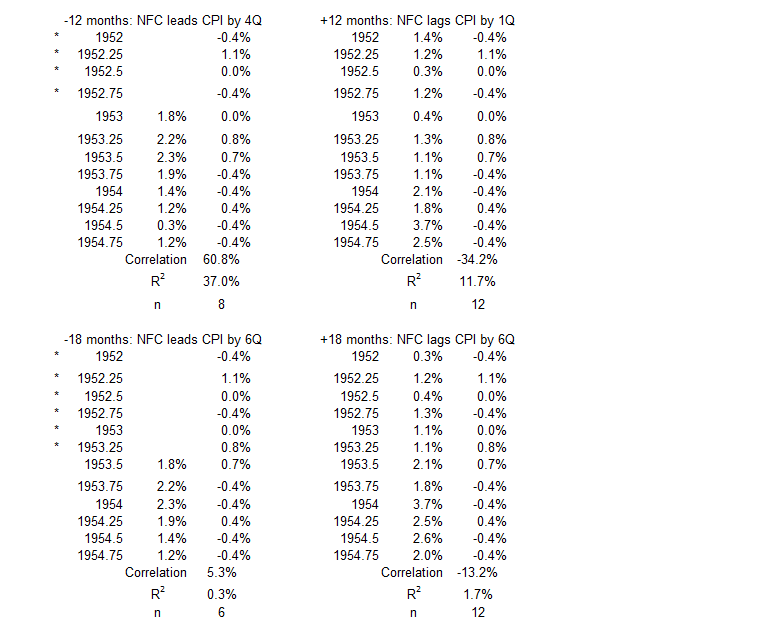

1Q 1952 – 4Q 1954

4Q 1974 -4Q 1976

2Q 1980 – 2Q 1983

4Q 1990 – 1Q 1998

3Q 2008 – 2Q 2009

Footnotes

1. Lounsbury, John, “Nonfinancial Corporate: Part 1”, EconCurrents, February 11, 2024. https://econcurrents.com/2024/02/11/nonfinancial-corporate-credit-and-inflation-part-1/.

2. Lounsbury, John, “Nonfinancial Corporate Credit and Inflation: Part 2”, EconCurrents, February 18, 2024. https://econcurrents.com/2024/02/18/corporate-nonfinancial-credit-and-inflation-part-2/.

3. Hole, Graham, “Eight things you need to know about interpreting correlations,” Research Skills One, Correlation interpretation, Graham Hole v.1.0., October 5, 2015. https://users.sussex.ac.uk/~grahamh/RM1web/Eight%20things%20you%20need%20to%20know%20about%20interpreting%20correlations.pdf.