Revised: 18 June 2023.

The paper on Keynes is brilliant.

. . . . –Prof. John C. Medaille

Prequel

During a summer of intense intellectual struggle with the General Theory in 1965, I changed the idea of Saving into the concept of Hoarding (I squeezed all the excess verbiage from the word Saving and reduced it to Hoarding). This paper was written in July 1974; it was not accepted for publication by AER; under the guidance of Professor Franco Modigliani and Professor Meyer L. Burstein, it was expanded into The Economic Process (2002).

For its – second – annotation of this fundamental book, the Journal of Economic Literature (December 2017, p. 1642), writes:

“Expanded third edition presents the transformation of economic theory into Concordian economics, shifting the understanding of the economic system from a mechanical, Newtonian entity to a more dynamic, relational process.”

Abstract

This paper revises the “forms,” not the substance, of Keynes’ ideas. The first part of the paper analyzes weaknesses in Keynes’ original model; the second part suggests remedies and, ultimately, a new model of the macrosystem; the third part provides an overview of the implications of the new model.

Introduction

It is in the nature of things that the bold and elegant Keynesian synthesis should have given way to a generation of analysis. Recalling the closing sentences of the General Theory, we would indeed upset Keynes’ calendar concerning the development of economic ideas were we not now to provide a new synthesis. An initial attempt toward this aim is presented in this paper.

The source from which we shall draw is, of course, the General Theory – a work which, very few have consistently denied, represents a marking stone in the development of economic thought. To acknowledge the significance of that work, however, should not prevent one from assessing its weaknesses. Indeed, as shall be seen, Keynes himself was fully aware of those weaknesses. They centered around the choice of the “forms” he adopted to express his ideas.

The first section of this paper shall analyze those weaknesses; the second section shall suggest remedies and, ultimately, a new model of the macrosystem; the third section shall provide an overview of the implications of the new model.

Section I

A few months after the General Theory was published, Keynes warned his early critics:

“I am more attached to the comparatively simple fundamental ideas which underlie my theory than to the particular forms in which I have embodied them, and I have no desire that the latter should be crystallized at the present stage of the debate.”1

In the same article, as shall be seen later on, Keynes even changed those forms – and changed them along the lines suggested here. Yet, not too much weight has evidently been attached to his words; and not too much weight shall be attached to this argument in this paper.

We shall rather try to heed that warning.

The Keynes Model

The overall mold into which Keynes cast his thought is the well-known model:

where, Y = income; C = consumption; I = investment; S = saving.

Instead of analyzing how the model works (or it is presumed to work2), we shall step out of its internal logic and consistency and shall analyze the definitions of each one of its component parts. It is well, in fact, to remember that the validity of that model resides in pure logic. Or, enlarging the range of application of the following words by Abba Lerner:

“It follows from and is implicit in our definitions of income, consumption, savings and investment, and the postulate that in any period moneys paid out are equal to moneys received.”3

Once those definitions are accepted, it is illogical to take issue with any of the implications inherent in that model. This is not the line of thought followed here. We shall rather isolate those definitions from the model and shall take issue with them directly.

Analysis of Saving

We shall start with the analysis of the concept of saving. This concept is not formally defined in the General Theory. The most precise definition which, with the help of Leijonhufvud, one can reach is that of “non-consumption.”4 As Keynes was well aware, this is an “old-fashioned” definition.5 It has a formal validity only in relation to its equality to investment. (A relationship which was powerfully reinforced by the formulation of Keynes’ model.) Yet, substantially – as Keynes stressed – this definition of saving is “incomplete and misleading.”6

It assumes that all individual savings are indeed investment; that they indeed represent a net addition to (or at least a replacement of) the national stock of investment. Instead, as Keynes repeatedly emphasized, savings can be simple transfers of wealth among individual persons.7 Thus, that definition is incomplete. And it can also be misleading because it explains away what in the first decades of the last century, especially through the inquiry of Robertson and Keynes, came to be identified as the central economic problem: the “savings-investment nexus”; or, in different terms, how savings are transformed into investment; or, at a deeper level of analysis, the reasons for the fluctuations in the rate of investment.8

The merits of these issues are well-known and do not need to be restated. What is important to stress is:

- that there are inherent weaknesses in the definition of saving used by Keynes, and

- that Keynes was well aware of these weaknesses.

Savings and Investment

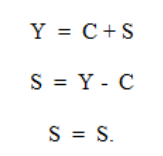

A simple operation shall highlight this point. In mathematics, one of the conditions of equivalence is that the terms be symmetric.9 If the equivalence of S to I, therefore, is valid, one should be able to substitute one of the terms with the other and obtain the same logical results. Substituting S with I in the first equation of Keynes’ model, one obtains the following results:

From this conclusion, it is impossible to reconstruct the equivalence of S to I without running into the error against which Keynes repeatedly warned:

The error lies in proceeding to the plausible inference that, when an individual saves, he will increase aggregate investment by an equal amount. It is true, that, when an individual saves he increases his own wealth. But the conclusion that he also increases aggregate wealth fails to allow for the possibility that an act of individual saving may react on someone else’s savings and hence on someone else’s wealth.10

With two more statements, Keynes left little room for misunderstanding.

First:

“Every such attempt to save more by reducing consumption will so affect incomes that the attempt necessarily defeats itself.”11

Second:

“This is the vital difference between the theory of the economic behaviour of the aggregate and the theory of the behaviour of the individual unit, in which we assume that changes in the individual’s own demand do not affect his income.”12

Investment is Operational

Without entering too deeply into the merit of the issues, it might be well to point out how – it is here believed – Keynes overcame the weaknesses in the definition of saving. In the General Theory and afterward (but not in the Treatise on Money, obviously13) – when speaking of the equality of S to I, – Keynes repeatedly refused to give any content to the concept of saving. While he provided a detailed list of the content of investment, 14 he steadfastly refused to provide any such list for the concept of saving. Neither did he ever state that its content was identical to that of investment. Rather, he used such similes as

“bilateral character of the transactions between the producer on the one hand and, on the other, the consumer and purchaser of capital equipment”;15

or, “two-sided transaction” represented by the depositor’s relation to his bank; 16 or

“there cannot be a buyer without a seller“;17 or

the law of demand and supply.18

In other words, he consistently refused to give to the concept of saving its traditional content.

Saving is not Operational

It seems clear, whenever he spoke of the equality of S to I, Keynes simply talked of saving in terms of investment – not the other way around. The difference is substantial. For every increase (or decrease) of investment, there must be an increase (or decrease) of assets; and these assets must necessarily be owned by somebody; they must correspond to someone’s “savings.”19

Yet, every increase (or decrease) of saving will not correspond to an increase (or decrease) of investment.

This device, together with his warning that the definition of saving he had accepted is “incomplete and misleading,” left him free to analyze some of the concrete functions which saving – independent of investment – performs in the economic system.20

Analysis of Investment

Keynes then felt free to proceed with his analysis of the concept of investment – the analysis which he really meant to concentrate upon in the General Theory. Of concern here is neither this analysis nor the definition of investment – provided this concept is agreed to mean any addition to (or replacement of) the stock of productive wealth or all productive wealth per se. Of concern here are the implications of this concept.

The Motor of the Economic System

The first obvious implication is that investment is assumed to be the motor of the economic system. This implication is so obvious and evidently so taken for granted that two of its ineluctable consequences are rarely taken into consideration:

- If the abstract concept of investment is related to concrete human beings, it must be concluded that the motor of the economic system is the entrepreneur; 21 and

- If, as Keynes pointed out, Consumption – to repeat the obvious – “is the sole end and object of all economic activity,”22

then it must be concluded that there is a minor contradiction in point of logic here: the dictates of deductive logic should compel one to start the analysis from the ultimate end – consumption – and not an intermediary one such as investment.

Logical Flaw

The second implication of the concept of investment is perhaps more serious. The equation Y = C + I can be considered simultaneously with the equation S = Y – C only if the entrepreneur – in his official capacity, not as a private individual – can ever be assumed to engage in the act of saving. Yet, in strict logic and outside of the validity of the equality of S to I, the entrepreneur cannot functionally save and invest – either at the same time or at successive periods. Retained earnings by a corporate enterprise clearly represent investment either imposed upon or allowed by the stockholders – and so are the retained earnings of an unincorporated enterprise. They represent income that, more or less consciously, is automatically reinvested. Retained earnings cannot represent savings unless the meaning of this term is bent out of recognition to suit every purpose.

The Entrepreneur and the Consumer

Those two equations (Y = C + I and S = Y – C) cannot be made to refer to the consumer either because otherwise, the entrepreneur is eliminated from the field of observation. Even less tenable would be the proposition that the first equation refers to the entrepreneur and the second to the consumer. Yet, these are the only alternatives warranted by that model; and none is entirely satisfactory.

Consumption and Destruction of Wealth

The concept of consumption as used in Keynes’ model also presents some difficulties. This concept has two meanings, yet only one of them – the negative one – is stressed in that model. (In contrast to the model, the General Theory stresses instead the second meaning.)

Etymologically, consumption means:

- to take wholly or to destroy;

- to spend.

Destruction of wealth occurs only with obsolescence and natural or man-made disasters, such as earthquakes and wars. (It must be stressed that we are speaking here of destruction in economic and not in physical terms.) Taken over a long period of time, the weight of this form of “consumption” is rather minimal. By far, the most important case is the other one: the case in which consumption is a synonym for spending. If the field of observation – as taught in particular by the General Theory – is the national economy and not the individual person, then the major economic function of consumption is simply a transfer of wealth.23

Writing S = Y – C and S = I, this economic function of consumption is, however, underplayed and perhaps even confused with the first. A superficial reading of the model would suggest this interpretation: the more spent on consumption, the less saved and the less available for investment. If this were the message of the General Theory, it would have hardly elicited strong criticism from so many economists; 24 it would have hardly supported Keynes’ hopes that he was writing a book that would “revolutionize” economic thinking.25

Income

There also are in that model two implications of the concept of income defined as consumption plus investment that are worthy of note. With this definition, Keynes fostered a trend to look forward, which is not in full agreement with his belief that

“…we have, as a rule, only the vaguest idea of any but the most direct consequences of our acts.”26

This consideration assumes a special significance if

- this tendency to look forward is seen as giving great encouragement to economic planning,27 and

- if economic planning is seen as a great departure from the classical tradition of primarily observing facts, events that have already happened and not venturing too far and too deep into the world of the future, that are – by definition – unknown.28

The above has nothing to do with analysis and forecasting as agents which alter the future.

With income defined as consumption plus investment, the second implication is that there is a need to distinguish between consumption and investment. And yet, such a distinction must be arbitrary. As Keynes pointed out,

“Any reasonable definition of the line between consumer-purchasers and investor-purchasers will serve us equally well, provided that it is consistently applied.”29

The Distinction between Consumption and Investment

Were Keynes’ model (as well as the second generation of models which formally30 followed it) not used so much with the aim of arriving at predictions about the future but as a tool to understand the economic process – as Keynes undoubtedly intended it, – the arbitrary distinction between consumption and investment would not have direct practical consequences.

This is not the case, however.

Those models are used to make predictions about the future and influence economic policy, and that arbitrary distinction – coupled with the definitional problems of the concept of consumption – is bound to have an effect. The autonomous and direct impact which consumption has (or can have) on the economic process is bound to be discounted. The most famous historical case in point appears to have been the fate of the forecasts which were made toward the end of World War II. With the exception of W. S. Waytinsky, all other economists grossly misjudged the future.31

Finally, the concept of wealth in Keynes’ model is largely left indeterminate.

Logical Difficulties with Keynes’ Model

In summary, all major definitions in Keynes’ model seem to present some logical difficulties which can escape attention for a variety of reasons:

- the concept of saving is made to perform a “passive” role;32

- the flaws in the concept of investment are covered by its equivalence to the concept of saving;

- the concepts of income and wealth are derivative concepts and therefore assume secondary importance; and

- it is rare that consumption takes the major lead as the spur of the economic process.

Those flaws, however, are there, and very few might deny that a model without those flaws should be able to produce better results. We shall now attempt to reach new definitions of the same economic concepts and build a new model.

Section II

The starting point shall be the definition of income. Keynes, in fact, pointed out that this definition was one of the “three perplexities which most impeded (his) progress in writing” the General Theory.33 This time, we shall approach the task from the point of view of the consumer.

The first equation shall therefore be:

Y = C + S (1)

where the symbols represent the same concepts as in Keynes’ model, but their definitions and their relationships to each other are different.

The suggested equation of income is self-evident. It refers to the use to which income is put by the consumer.34 And income must be either spent or saved. In the 1937a article,26 Keynes wrote, p. 190:

“… an increase in income will be divided in some proportion or another between spending and saving…” ( Y = C + S).

Only one objection can be raised against this equation. At first sight, it excludes investment from the field of observation. It shall be seen, however, that this objection is not valid in terms of the model we are trying to build. Investment shall be taken into account. Hint: In Concordian economics, it is included in C: One buys consumer goods, capital goods, and goods to hoard.

Sidebar

Before proceeding any further with the task of model building, let us pause to analyze the definition of a key concept included here, that of saving.

It seems that clarity of economic discourse would compel us to have a concept of saving that is independent of any other economic term. Such independent meaning, it is maintained here, can be reached only if saving is made to represent all wealth that can neither be consumed nor can be confused with investment. If this condition is accepted, then the concept of saving can be made to cover exclusively all forms of unproductive wealth – i.e., gold, unproductive land, jewels that are never worn, cash in a vault, etc. [To avoid confusion, the word “saving” was eventually substituted with the word “hoarding.”]

These are all forms of wealth that can indeed be saved. They do not lose any value over time. On the contrary, since their carrying costs are either negligible or nil and since the history of the world is a history of inflation, with the exception of cash in a vault, these forms of wealth generally acquire value over time.

Savings and Wealth

One of the chief benefits of writing Y = C + S is the fostering of the immediate recognition that an increase in S improves one’s balance sheet, but it does not increase national wealth. An increase in savings ultimately does not even increase personal wealth; with saving defined as above and in the absence of inflation, saving can not even do that. In the final analysis, whatever gain is shown in the personal balance sheet at the end of the year has been acquired at the expense of one’s own consumption and/or investment potential.

Another chief benefit of writing Y = C + S might be the possibility of arriving at more precise forecasts of the future in periods that – like the current one (summer of 1974) – there seems to be a flight from productive investments and a strong tendency to “invest” in unproductive wealth as an edge against inflation.

Once the concept of saving is defined, investment becomes an equally very definite concept – i.e., all productive wealth, all wealth that produces income, goods, and services.

Thus we have (almost) all the necessary elements to build the second equation in our model.

Consumption and Investment

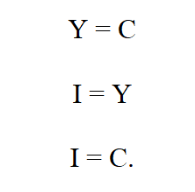

If the second equation of Keynes’ model is maintained, one simply holds an empty and inoperative tautology. If one changes it to I = Y – C, one reaches the conclusion that I = S. This conclusion is untenable, not only because it reverses the problems mentioned in the previous section in relation to Keynes’ model, but because – recalling the newly reached definition of saving – one would equate productive wealth to unproductive wealth. Neither can one conveniently introduce any other term – such as credit, for instance – to build the second equation.

Once the definition of saving is firmly established, preferably as suggested above, the second equation must inescapably be:

I = Y – S (2)

Combining (1) and (2), one reaches the conclusion that I = C. Before analyzing this new equivalence, let us focus our attention on the resulting definition of consumption.

Consumption, in accordance with the new model, is all wealth that is used either for the production of other goods or for direct enjoyment. The arbitrary distinction between investment and consumption mentioned above loses any practical or theoretical value. In the proposed model, I = C.

Consumer Goods and Capital Goods

This equivalence becomes intelligible as soon as one disaggregates C into consumption of consumer goods (let us say Cc) and consumption of capital goods (Ck). The equivalence of I to C thus becomes I = Cc + Ck.35 (Or, more precisely, C = Cc + Ck and I = Fc + Ck, where Fc stands for finished Consumer Products; and, since Fc = Cc, then I = C.)

The equivalence of I to Cc + Ck echoes the classical distinction between, respectively, “unproductive” and “productive” consumption. This immediately conveys the meaning attributed to consumption in the General Theory. It is “modern” in the sense that it gives the consumer the role of prime mover in the economic system. (The consumer decides to spend his income directly on consumer goods or buys a plot of land, a house, a machine shop, or even decides to hire a professional entrepreneur to look after his interests.)

This equivalence is also historically and logically correct. The first act of production – i.e., reaching for the apple (?) on the tree – must have been indistinguishable from an act of consumption. Today, in a money economy, this relationship should be even more evident: an act of production makes consumption possible, and consumption, in turn, creates a new need for production. Indeed, in a money economy, with an act of consumption, one does not only convey the message of a need for more production; one even transfers the financial resources which allow others to continue their productive activity and prosper.

Wealth

Logically, there is no difference between an act of consumption and an act of investment. At least, entrepreneurs do not see any such difference. They look at other entrepreneurs as consumers – consumers just as the apple-eaters. They scan the market and produce, not in accordance with any such distinction, but in accordance with the availability of purchasing power which is ready to be spent, or, as Keynes would say, availability of “effective demand” in the market.36 Certainly, neither duration of life nor ability to produce further wealth are inherent qualities of investment vs. consumption goods. Dried apples can outlast machines; one can make juice and tarts from apples.

The only difference between investment and consumption goods resides in their intended use: the former are used to produce further wealth (i.e., delayed and indirect consumption satisfaction); the latter are used to derive direct satisfaction and enjoyment. Yet, as far as use or “consumption” is concerned, there is no difference here. Both types of goods are consumed.

Once the definitions of the three major concepts – i.e., consumption, investment, and saving – are accepted as valid, the definition of income as the sum of consumption and saving is also confirmed as valid. Indeed, using the disaggregate form of consumption, the definition of income becomes: Y = Cc + Ck + S. This definition, if seen as the value of stocks and not as a flow of funds, immediately yields a precise definition of wealth (W):

W = Cc + Ck + H

This definition is in accordance with common wisdom which says: out of last year’s income, I consumed “x”, invested “y”, and saved “z”.

A 2020 Addition

In the course of time, Investment (I) was translated into Production (P), and the theory of distribution of ownership rights was integrated into the economic discourse. The law abhors a vacuum. Thus as soon as any monetary or real wealth is created, its ownership is automatically apportioned to someone. The Theory of Distribution (of wealth) thus completes the I = C equivalence, by transforming it into Production Distribution Consumption, or P = D = C. Either expression is better formulated in geometric terms. Thus:

This Figure reads as follows: There are three elements in any exchange of wealth. Even for the purchase of a chocolate bar, there is an exchange of (1) money for (2) wealth and (3) the delivery of proof of legal purchase expressed by the sales slip.

In the course of time, I have learned with great pleasure of Galileo‘s remonstrance: I did not put those items up in the sky…

Section III

It is believed that the proposed model does not only eliminate those flaws from Keynes’ model that have been discussed above; it also makes the ideas expressed in the General Theory of more immediate apperception. The value of the proposed model, however, has not only an academic value; it does not only provide a new classification of economic terms and eventually make the exegesis of the General Theory relatively easier to expound. Rather, it is pleasant to believe, the value of this model resides in its application to economic theory and policy.

This model might give rise to a new Theory of Growth. Through the prism of the proposed model, it can immediately be seen that economic growth can occur not only through an exogenous influx of public investment – as, in the end, due to the immediate circumstances Keynes felt obliged to suggest.

Savings can be Invested or Consumed

Economic growth can also occur through a reduction of private (as well as, indeed, public and corporate) savings [hoarding]. Thus, savings can be either invested or consumed: i.e., gold can be used for dentistry (?) and art, unused land for housing and recreation, etc. At the limit, with S = 0, the proposed model reads:

Needless to say, increased investment – together with increased consumption – in “year” 1, is going to produce a bigger income in “year” 2. And, if the proportion of income spent on the two items (consumer goods and capital goods) is in relation to their respective production, there will not be any inflation.

Also needless to say, implied here is not the economics of perfect calculations, ease, and abundance. There will always be errors in judgment. It will always take effort to produce wealth, and there will always be temporary limits to the economic process set not only by the availability of purchasing power and readiness to spend it, but also by the availability of human as well as natural/artificial resources.

The suggested adaptation of the proposed model to the Theory of Growth might also begin to give us a new understanding of the inflationary process. Here only the two crucial events in this process shall be outlined.

First:

Any purchase of unproductive wealth – even at the bottom of the recovery – is, by definition, inflationary. An amount of money is injected into the economy for which there is no corresponding increase in goods and services. The flow of the economic process is cut into two – with one half left frozen, or unproductive of further income and/or goods and services, and the second half fluctuating.

This second half might be directed toward the purchase of more unproductive wealth. Then the negative effects of the action of the first marginal operator might become cumulative. Indeed, the entire process has to be seen over time as accompanying, or, perhaps better, itself constituting the business cycle.

(At the bottom of the cycle, demand for unproductive wealth is almost zero; and the effective demand for productive wealth begins to grow. At the peak of the recovery, the composition of the aggregate demand function is reversed).

Second:

The next crucial event on which we shall lightly touch occurs toward the peak of the recovery when the largest part of the flow of money still runs into productive wealth: investment outlets become scarcer, the marginal efficiency of capital decreases (or is believed to decrease), and “the” interest rate rises – not so much because the supply of money is somehow deficient as because its demand is abnormally high. This increased “liquidity preference,” in turn, is due to a large number of factors, some of which shall be listed below:

- the flow of money reverses its course (hence an increased demand for it) from investment goods back into comparatively scarce unproductive wealth; namely, savings or presumably secure wealth;

- the financial needs of the productive process must somehow be satisfied, and they will be satisfied through borrowing;

- financial fortunes are lost in the bear market;

- the price of unproductive wealth increases;

- the price of consumer goods also increases. With ongoing disinvestment and high interest rates, the productive process begins to provide less than the peak flow of such goods and services;

- the price of investment goods also increases, while their production decreases;

- less money income – both in the form of labor income and capital income – is created and distributed;

- less revenue is received by the productive process because of a lower consumption rate.

These processes are, of course, largely circular in nature. They tend to reinforce each other. Certainly, not enough of the economic process has been observed here and not at sufficient depth to suggest any economic policy which might be followed in the presence of current events or at any other time. One general observation, however, might be warranted:

If the above propositions are deemed to possess any value, eventually they will unavoidably influence economic policy. There is certainly a great difference between a diagnosis – as Keynes’ model suggests – that economic ills stem from a volatility of investment, and a diagnosis – as suggested by the proposed model – that economic ills stem from a cyclical desirability of unproductive wealth. The economic policy which flows (or should flow) from one diagnosis has to be different from the economic policy which flows (or should flow) from the other.

Concluding Comments

The issues dealt with here certainly deserve more attention than it was possible to give them. The main concern, however, was not the treatment of the many substantive issues as the desire to submit the proposed model to the evaluation of the academic community.

Obviously, a model is only a tool. By itself, it does not do any work. A better tool – as hopefully has been built here – only has the potential of assisting in doing better work. Ultimately, the value of the model must be judged in relation to the value of the amount of theoretical and empirical work which lies ahead.

In other words, what is requested of the academic community is to pass a partial and suspended judgment on the potential value of the proposed model.

References

A. H. Hansen, Monetary Theory and Fiscal Policy, New York 1949.

S. E. Harris, The NewEconomics, New York 1947.

R. F. Harrod, The Life of John Maynard Keynes, New York 1951.

F. A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, Chicago 1944.

H. G. Johnson, “The General Theory after Twenty-five Years,” Amer. Econ. Rev. May 1961, Vol. LI, No. 2.

N. Kaldor and J. A. Mirrlees, “A New Model of Economic Growth,” in F. H. Hahn, ed., Readings in the Theory of Growth, New York 1971.

J. M. Keynes, A Treatise on Money, 2 Vols., New York 1930.

_____, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, New York 1936.

_____, “The General Theory of Employment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics,

February 1937a, reprinted in S. E. Harris, ed., op. cit.

_____, “Alternative Theories of the Rate of Interest,” The Economic Journal, June 1937b.

L. R. Klein, The Keynesian Revolution, 2d ed., New York 1966.

A. Leijonhufvud, On Keynesian Economics and the Economics of Keynes, New York 1968.

R. Lekachman, The Age of Keynes, New York 1966.

A. P. Lerner, “Savings Equals Investment,” reprinted in S. E. Harris, ed., op. cit.

P. Suppes, Introduction to Logic, Princeton 1957

Footnotes

1. Keynes, 1937a, p. 183.

2. Cf. Klein, esp. p. 83.

3. Lerner, p. 625. The author was making exclusive reference to the equality of S to I.

4. Leijonhufvud, pp. 28-29.

5. General Theory, p. 83 and Keynes, 1937b, p. 249. To be precise, Keynes used the qualification “old-fashioned” for the entire proposition of the equality of S to I. The emphasis, however, was on the concept of saving.

6. General Theory, p. 83.

7. Ibid., esp. pp. 83-85 and 212.

8. Ibid. Cf. also Lekachman, pp. 67-73.

9. Suppes, pp. 213-220.

10. General Theory, pp. 83-84. Cf. also pp. 177-178.

11. Ibid., p. 84.

12. Ibid., p. 85.

13. Treatise, esp. Vol. I, pp. 123-126.

14. General Theory, esp. pp. 74-75

15. Ibid., p. 63.

16. Ibid., p. 81.

17. Ibid., p. 85.

18. Keynes, 1937b, p. 249.

19. This interpretation implies that the equilibrium between saving and investment is instantaneous and continuous. In the General Theory, pp. 183-184, Keynes in fact stressed that: “Saving and Investment are the determinates of the system, not the determinants. They are the twin results of the system’s determinants, namely, the propensity to consume, the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital and the rate of interest.” (Italics added). Cf. also p. 328.

Consequently, this interpretation also implies that one cannot accept Keynes’ classifications and admit a difference between ex-ante and ex-post saving (as Robertson is entitled to do), or between “observable savings” and “schedules of savings” (Klein, pp. 91-92 and 110-117), or between actual and desired savings (Hansen, p. 225), or any other such distinction.

On the other hand, it should not be denied that there are passages in the General Theory which – if read literally – might lead to a different interpretation than the one provided in the text. Cf., esp. pp. 74, 117, 122-123, and Chapter 14.

20. General Theory, esp. pp. 210-213.

21. The relevance of this observation resides in the obvious linkage which exists between economics and the larger social and cultural context: viz., the Protestant/Puritan ethic; viz., the social and political status accorded to the businessman in the contemporary world.

22. General Theory, p. 104.

23. The precise definition of consumption in the General Theory, p. 62, is drawn in terms of sales. And a sale is only a transfer of wealth. (Also, income is in the same page precisely defined as total sales minus aggregate user costs of the entrepreneurs – with user cost including the concept of obsolescence, destruction, etc.; see pp. 23, 53-55, 58 and 66-73).

24. Cf. Harris, Chapters III, IV and V, and esp. p. 29.

25. Cf. Keynes’ letter of January 1, 1935 to George Bernard Shaw quoted in Harrod, p. 462.

26. Keynes, 1937a, p. 184.

27. Cf. esp. Klein, Chapter VIII and p. 224.

28. Cf. esp. Hayek, Chapters I, IV, V, VI, VII and pp. 34-42.

29. General Theory, p. 61. Italics added.

30. Leijonhufvud, esp. p. 327 and Chapter III:2.

31. Lekachman, p. 164.

32. Kaldor and Mirrlees, speaking of the characteristics of their model, stated, p. 166: “… like all ‘Keynesian’ economic models, it assumes that ‘savings’ are passive…” (Italics added).

33. Johnson, p. 3; General Theory, p. 37.

34. In the 1937a article, Keynes wrote, p. 190: “… an increase in income will be divided in some proportion or another between spending and saving…” ( Y = C + S).

35. In the 1937a article, Keynes wrote, p. 190: “I say that effective demand is made up of two items – investment-expenditure … and consumption-expenditure.” (I = Cc + Ck).

36. In the 1937a article, Keynes wrote, p. 190: “Incomes are created partly by entrepreneurs producing for investment and partly by their producing for consumption.”

.