On the third Thursday of the month right on schedule NOAA issued their updated Seasonal Outlook which I describe as their Four-Season Outlook because it extends a bit more than one year into the future. The information released also included the Mid-Month Outlook for the following month plus the weather and drought outlook for the next three months. I present the information issued by NOAA and try to add context to it. It is quite a challenge for NOAA to address the subsequent month, the subsequent three-month period as well as the twelve successive three-month periods for a year or a bit more.

With respect to the long-term part of the Outlook which I call the Four-Season Outlook, the timing of the transition from Neutral to LaNina has been challenging to predict. But there is more confidence in the situation for the moment. We are still in ENSO Neutral. La Nina is the likely scenario very soon, but the strength of the La Nina may be fairly weak. The transition from ENSO Neutral to La Nina is complicated as is the transition from La Nino back to ENSO Neutral. We may have both of these transitions in the three-month period January through March which is a rapid sequence of transitions. So even if we have La Nina conditions for two or three months this period of time will probably not be recorded as a La Nina event because of the short duration. Every ten years the definition of climate normals are changed (it may be every five years for oceans). Some ENSO events are canceled and others are promoted to El Nino or La Nina status when the definition of climate normals (also called climatology) is updated. This applies to the ONI status only as they do not reexamine the connection with the atmosphere. The warming of the oceans may very well make our definition of the states of ENSO incorrect. NOAA is looking at that.

From the NOAA discussion:

“El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO)-neutral conditions are present, as equatorial sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are near-to-below average in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean. During the last four weeks, mostly negative SST anomaly changes were evident across the equatorial Pacific Ocean. As such, a La Niña Watch is in effect, with La Niña conditions most likely to emerge in November 2024 – January 2025 (NDJ) (59% chance) and is expected to persist through February-April (FMA) 2025. In fact, the latest weekly Nino 3.4 SST departure was -0.6 degrees Celsius, which technically crosses the La Niña threshold. However, chances of a strong La Niña are exceedingly small, with a near zero percent chance of occurrence through the Winter. ENSO-neutral conditions are favored to re-emerge by the March-May (MAM) 2025 season.”

I personally would not have total confidence in this outlook given the uncertainty about there actually being a La Nina and its strength and duration if it does happen. The number of El Nino and La Nina events since 1950 is a fairly small number. When you further segment them by strength (LINK) you end up with a very small number of events in each category (El Nino v La Nina and three or four categories of strength within each (thus 7 subcategories). This makes both statistical methods and dynamical models have a large error range. We are pretty confident now that we will have either a weak La Nina or Neutral with a La Nina bias meaning it will be in the Neutral Range but closer to a La Nina than the midpoint of ENSO Neutral. This suggests that there is value in this forecast. The maps show the level of confidence that NOAA (really the NOAA Climate Prediction Center – CPC) has for the outlook shown when they show a part of the U.S. or Alaska differing from normal.

It will be updated on the last day of November.

Then we look at a graphic that shows both the next month and the next three months.

The top row is what is now called the Mid-Month Outlook for next month which will be updated at the end of this month. There is a temperature map and a precipitation map. The second row is a three-month outlook that includes next month. I think the outlook maps are self-explanatory. What is important to remember is that they show deviations from the current definition of normal which is the period 1991 through 2020. So this is not a forecast of the absolute value of temperature or precipitation but the change from what is defined as normal or to use the technical term “climatology”.

| Notice that the Outlook for next month and the three-month Outlook are fairly similar except for temperatures in the Northwest and Alaska. This tells us that February and March will be substantially the same as January for most of CONUS. Part of the explanation for this is that NOAA expects La Nina to impact all three months. |

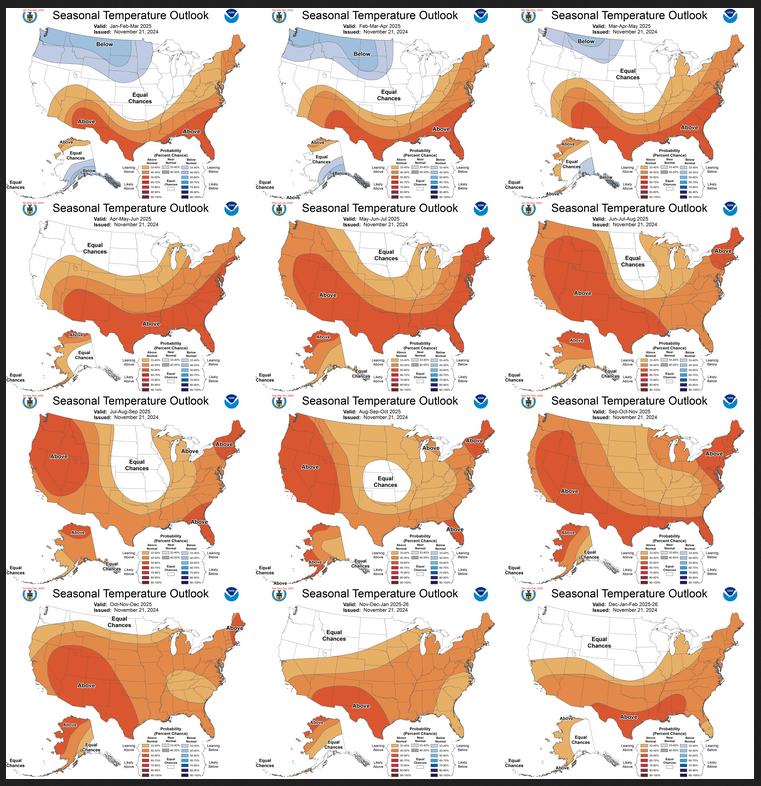

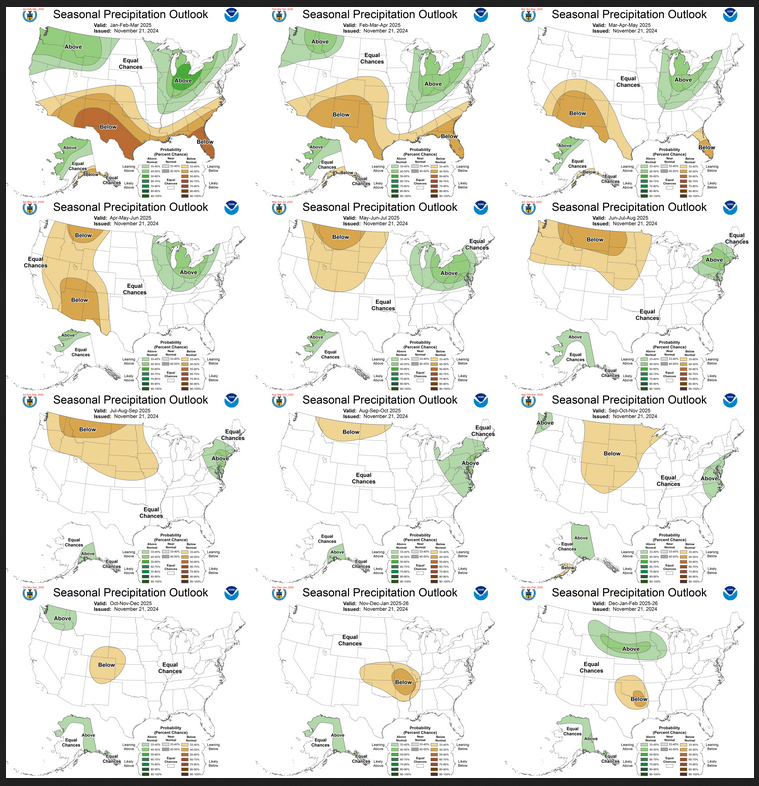

The full NOAA Seasonal Outlook extends through January/February/March of 2026 (yes that is more than a year out). All of these maps are in the body of the article. Large maps are provided for January and the three-month period January/February/March. Small maps are provided beyond that through January/February/March of 2026 with a link to get larger versions of these maps. NOAA provides a discussion to support the maps. It is included in the body of this article.

In some cases, one will need to click on “read more” to read the full article. For those on my email list where I have sent the url of the article, that will not be necessary.

The maps are pretty clear in terms of the outlook.

And here are large versions of the three-month JFM 2025 Outlooks

First temperature followed by precipitation.

| These maps are larger versions of what was shown earlier. This is a pretty definitive pattern. |

NOAA Discussion

Maps tell a story but to really understand what is going you need to read the discussion. I combine the 30-day discussion with the long-term discussion and rearrange it a bit and add a few additional titles (where they are not all caps the titles are my additions). Readers may also wish to take a look at the article we published last week on the NOAA ENSO forecast. That can be accessed HERE.

I will use bold type to highlight some especially important things. All section headings are in bold type; my comments, if any, are enclosed in brackets [ ].

CURRENT ATMOSPHERIC AND OCEANIC CONDITIONS

ENSO-neutral continued in November, with near to weakly below average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) observed across much of the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. The latest weekly Niño indices ranged from -0.2°C (Niño-1+2) to -0.6°C (Niño-3.4), with the magnitude of the negative Niño-3.4 anomaly technically crossing the La Niña threshold. Below-average subsurface ocean temperatures persisted across the east-central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. Over the western and central equatorial Pacific, low-level wind anomalies were easterly and upper-level wind anomalies were westerly. Convection was suppressed over the Date Line and was enhanced over western Indonesia. The traditional and equatorial Southern Oscillation indices were positive. Collectively, the coupled ocean-atmosphere system reflected ENSO-neutral. However, with SST anomalies across much of the Tropical Pacific trending more negative, a La Niña Watch remains in effect.

The Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) has continued to be a significant player in the tropics. However, the emerging La Niña base state has been a growing source of interference with both the propagation and amplitude of the MJO. Dynamical model forecasts depict continued eastward propagation of the MJO signal with a slow phase. Extended range Realtime Multivariate MJO (RMM) index solutions indicate the potential for a surge in the strength of the MJO during weeks 3 and 4 as it moves out into the Central Pacific and La Niña interference lessens. A continued eastward MJO propagation over the Pacific would favor a period of below-normal temperatures across the northeastern U.S. to start off the New Year, as well as a wet start for the West Coast. However, the majority of seasonal guidance for JFM favors above normal temperatures for the Northeast, suggesting that this cold period may be short lived.

PROGNOSTIC DISCUSSION OF SST FORECASTS

The dynamical models in the Columbia Climate School International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI) plume continue to predict a weak and a short duration La Niña. This prediction is also reflected in the latest North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME), which continues to predict slightly cooler SSTs and weak La Niña conditions. The ENSO forecast team leaned toward predicting an eventual onset of weak and short-lived La Niña conditions, based on the model guidance and current atmospheric anomalies. In summary, La Niña conditions are most likely to emerge in NDJ 2024-2025 (59% chance), with a transition to ENSO-neutral most likely by MAM 2025 (61% chance).

30-DAY OUTLOOK DISCUSSION FOR JANUARY 2025

Following a few months of weakly below normal sea surface temperatures (SSTs), SST departures reached -0.6 degrees Celsius in the Niño3.4 region over the past week. The current El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Alert System Status is a La Niña watch. The extended period of weakly below normal SSTs and recent drop to -0.6 degrees Celsius may lead to some La Niña-like impacts over the contiguous United States (CONUS) during January and the upcoming season, however, we expect that any impacts may be weak and variability to be high, leading to uncertainty in some of the typical impacts. Though the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) has been a significant player in the tropics in recent weeks and dynamical models depict continued eastward propagation of the MJO envelope with a slowed phase speed, the emerging La Niña has the potential to interfere with propagation and amplitude of the MJO. Should the MJO continue into January, this may lead to cooler than average temperatures for the northern parts of the CONUS and Northeast, but the potential interference from La Niña and slow phase speed add to the uncertainty. In addition to the large-scale drivers of La Niña and the MJO, coastal or local SSTs, sea ice, and snow cover are taken into account for this forecast where appropriate. Monthly forecasts of temperature and precipitation by dynamical models from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME), Copernicus Climate Suite (C3S), and CFSv2 were utilized in preparing this Outlook. Week 3-4 predictions for the first part of January from GEFSv12, ECMWF, and CFSv2 and the expected transition in the atmospheric pattern from the Week 2 period were also considered.

Temperature

Enhanced ridging is forecast over most of the CONUS toward the end of December, leading to the potential for above normal temperatures to end the year. However, this strong ridging is expected to moderate by the beginning of January, giving way to ridging over the West and neutral to above normal heights over the remainder of CONUS. Week 3-4 models forecasting the beginning of January favor weak ridging over the West and troughing over the East, though the position, exact timing, and strength of the pattern is uncertain. Given the atmospheric pattern leading into January and the forecasts for early January, we expect a warm start to the month followed by a transient pattern. Uncertainty is high due to the potential for this transient pattern, particularly for temperatures.

The January 2025 Temperature Outlook features above normal temperatures over the southern half of the western CONUS, Southern Plains, and the East Coast. This pattern is fairly typical of La Niña, and reflects dynamical model predictions that favor a La Niña like response for the month. However, given the expected transient height pattern during the month, probabilities are overall low for temperatures. Probabilities are enhanced over the Southern Plains where there was the best agreement among available tools. Some models such as the C3S suite and CFSv2 favored higher probabilities of above normal temperatures over the Southwest, however, NMME and statistical tools that include decadal trends which are below normal in parts of the Southwest more strongly favor near-normal temperatures. Given this discrepancy, a weak tilt toward above normal temperatures is favored despite some of the model results showing stronger probabilities in the region, which also aligns with forecast below normal precipitation in the region. Similarly, some models indicate stronger probabilities for above normal temperatures over the East Coast relative to the Outlook, but given Week 3-4 models that tilt toward below normal temperatures over the East, probabilities are again weakened. Equal chances (EC) of above, near, and below normal temperatures are favored over the northern tier of the CONUS and Central Plains where tools had weak or uncertain signals, and, moreover, both MJO and La Niña may lead to cold air intrusions into the region, though both influences are currently somewhat uncertain. In addition, given the forecasted warm start to the month of January, it is uncertain if periods of colder temperatures will be strong or long enough to tilt the probability to below normal over the northern tier. Over Alaska most models favored above normal temperatures, particularly CFSv2, and as such a tilt toward above normal temperatures is indicated in the Outlook.

Precipitation

Despite the transient pattern, precipitation signals were more consistent in tools than temperatures. While SSTs in the Niño3.4 region just recently dropped below -0.6 Celsius, it is possible that tools are picking up the extended period of weakly below normal SSTs and forecasts of a weak La Niña as many of the tools are showing a La Niña like precipitation pattern over the CONUS. For example, both NMME and C3S probabilistic multi-model ensemble probabilistic forecasts show a general pattern of below normal precipitation over the southern tier of CONUS, and above normal precipitation over the Northwest and Great Lakes and interior Southeast, which are hallmarks of a La Niña pattern. The January 2025 Precipitation Outlook thus resembles a La Niña like pattern, featuring enhanced probabilities of above normal precipitation over the Intermountain West and parts of the Northern and Central Plains, the Great Lakes and interior Southeast, and a tilt toward below normal precipitation from the Southwest along the southern CONUS and parts of the coastal Southeast. Over Alaska, above normal precipitation is favored for western and northern parts of the state, with a small area of below normal precipitation over its southern coast. Some uncertainty exists along the West Coast where EC is indicated. NMME and C3S favor below normal precipitation over the southern West Coast and above normal precipitation over the northern West Coast, while CFSv2 tilts toward below normal over the northern West Coast. Given the potential for periods of above normal precipitation over the West Coast during winter months, EC is favored despite some of the tools leaning toward below normal. Models and tools also had mixed signals along the coastal northeast and New England, and there is potential for variability during the month due to uncertainty in storm tracks, leading to the favored region of EC. Finally, over Alaska, below normal precipitation is favored over its southern coast given La Niña teleconnections, and above normal is favored over the western and northern parts of the state given La Niña teleconnections, dynamical model agreement, and above normal decadal trends over the northern coast.

SUMMARY OF THE OUTLOOK FOR NON-TECHNICAL USERS (Focus on January through March)

El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO)-neutral conditions are present, as equatorial sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are near-to-below average in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean. During the last four weeks, mostly negative SST anomaly changes were evident across the equatorial Pacific Ocean. As such, a La Niña Watch is in effect, with La Niña conditions most likely to emerge in November 2024 – January 2025 (NDJ) (59% chance) and is expected to persist through February-April (FMA) 2025. In fact, the latest weekly Nino 3.4 SST departure was -0.6 degrees Celsius, which technically crosses the La Niña threshold. However, chances of a strong La Niña are exceedingly small, with a near zero percent chance of occurrence through the Winter. ENSO-neutral conditions are favored to re-emerge by the March-May (MAM) 2025 season.

Temperature

The January-March (JFM) 2025 temperature outlook favors above-normal temperatures for most of the southern tier of the Contiguous United States (CONUS), the eastern quarter of the CONUS, and northern Alaska. The largest probabilities (greater than 50 percent) of above normal temperatures are forecast across parts of the Southwest, the Rio Grande Valley, the Gulf Coast Region, and the Southeast. Conversely, a weak tilt toward below normal temperatures is indicated for southeastern Alaska, the northwestern CONUS, and the Northern Plains.

Precipitation

The JFM 2025 Precipitation Outlook depicts enhanced probabilities of below-normal precipitation amounts across much of the southern tier of the CONUS as well as parts of southern Mainland Alaska. The greatest chances (greater than 50 percent) of below-normal precipitation are forecast for the Rio Grande Valley and the Florida Peninsula, where probabilities of below exceed 50 percent. Above-normal precipitation is more likely for the northwestern CONUS, the Great Lakes, Ohio Valley, parts of the Upper and Middle Mississippi Valley, parts of the interior Northeast, and much of northern and western Mainland Alaska. The greatest chance (above 50 percent) of above-normal precipitation is indicated for the central Great Lakes region and northern portions of the Ohio Valley. Equal chances (EC) are forecast for areas where probabilities for each category of seasonal mean temperatures and seasonal accumulated precipitation amounts are expected to be similar to climatological probabilities.

BASIS AND SUMMARY OF THE CURRENT LONG-LEAD OUTLOOKS

PROGNOSTIC TOOLS USED FOR U.S. TEMPERATURE AND PRECIPITATION OUTLOOKS

Dynamical model forecasts from the NMME, the Coupled Forecast System Model Version 2 (CFSv2) , the Copernicus (C3S) multi-model ensemble system were used extensively for the first six leads when they are available, as was the objective, historical skill weighted consolidation and Calibration, Bridging, and Merging (CBaM) guidance, that combines both dynamical and statistical forecast information.

Additionally, the official ENSO forecast favors a weak La Niña through the upcoming winter. This anticipated weak La Niña signal played a role in the construction of these outlooks. Composites derived from nearest neighbor statistical analysis of recently observed tropical Pacific SST and Equatorial heat anomalies were utilized where appropriate. At later leads, decadal trends in temperature and precipitation were increasingly relied upon in creating the seasonal outlooks.

PROGNOSTIC DISCUSSION OF OUTLOOKS – JFM 2025 TO JFM 2026

TEMPERATURE

Above-normal temperatures are favored throughout most of the southern tier and eastern quarter of the CONUS and northern Alaska during JFM. Conversely, below normal temperatures are more likely for much of southeastern Alaska, the northwestern CONUS, and the Northern Plains. EC of below, near, or above normal temperatures are forecast for most of California, parts of the Great Basin, the Central Rockies and Plains, the western Great Lakes Region, and central and southwestern Alaska. These EC areas are due to weak or conflicting signals among temperature tools. Probabilities of below-normal temperatures are reduced slightly relative to last month across parts of the north-central CONUS as cold statistical tools are tempered by warmer dynamical based guidance. The greatest probabilities of colder than normal conditions (40 to 50 percent chance) are forecast for parts of southeastern Alaska, Pacific Northwest, and Northern Rockies, where guidance is in better agreement. Above normal temperatures remain likely (greater than 50 percent chance) across the parts of the Southwest, the Rio Grande Valley, the Gulf Coast Region, and the Southeast, and favored (between 40 and 50 percent chance) across the remainder of the Eastern Seaboard due to good agreement among both dynamical and statistical guidance. Guidance is similar across much of Alaska relative to last month. Increased probabilities of below-normal temperatures are indicated for southeastern parts of the state, supported by ENSO composites and dynamical model guidance. Above-normal temperatures remain favored for northern Alaska due, in part, to recent trends .

For FMA, potential impacts from the predicted weak La Niña continue and the predicted temperature pattern is very similar to JFM. Above-normal temperatures continue to be favored across most of the southern tier of the CONUS, the Eastern Seaboard, and northern Alaska. Enhanced probabilities of below normal temperatures persist across southeastern Alaska, the Northwestern CONUS, and the Northern Plains. Probabilities of below-normal temperatures were increased for parts of the northern High Plains relative to the JFM season due to recent trends . By MAM, the potential impacts of La Niña begin to wane as ENSO-neutral conditions become increasingly likely. As such, the areas of favored below-normal temperatures across southeastern Alaska, the Northwestern CONUS, and the Northern Plains diminish relative to FMA. Above normal temperatures remain favored across much of the southern tier of the CONUS and Eastern Seaboard. However, confidence in above-normal temperatures is reduced across parts of the Great Lakes region relative to last month as composites derived from recent ENSO observations are indicating a cold signal. As we progress to later in Spring (April-May-June (AMJ)) through early Fall (September-October-November (SON)), the favored below-normal areas disappear completely. However, above-normal temperatures continued to be favored for much of the West, southern tier, and East Coast of the CONUS as well as much of coastal Alaska and parts of the interior Mainland, consistent with trends. Large areas of EC are indicated across much of the central CONUS and parts of Alaska due to weak or conflicting signals among the guidance. Later in the Fall (October-November-December (OND)) into early winter NDJ 2025-2026, slightly enhanced probabilities of above-normal temperatures are indicated across most of the country, consistent with recent trends . Large areas of EC are indicated for the heart of next Winter (December-January-February (DJF)) 2025-26 and JFM 2026 as confidence decreases at these longer leads. [Author’s Comments: These are really unexplained changes from the maps provided last month so one wonders about the real reason for the change.]

PRECIPITATION

During JFM and FMA 2025, the forecast precipitation patterns are very similar and exhibit many of the hallmarks of a La Niña signal. Above normal precipitation is favored during both seasons for the Northwestern CONUS, Great Lakes, Ohio Valley, parts of the Upper and Middle Mississippi Valley, interior Northeast, and northern and western Alaska. The greatest confidence of above-normal precipitation is indicated across the central Great Lakes region and northern Ohio Valley during JFM. Below normal precipitation is favored across much of the southern tier of the CONUS for JFM and FMA as well as for parts of the South Coast of Mainland Alaska. Confidence of below-normal precipitation is generally greater across the southern tier of the CONUS during JFM relative to FMA. However, a notable northward expansion of the favored below-normal precipitation area is indicated for parts of the west-central CONUS during FMA. For both JFM and FMA, the area of enhanced above-normal precipitation probabilities in the east-central CONUS is expanded southwestward relative to last month to include more of the Central and parts of the Lower Mississippi Valley due to dynamical model support. Confidence for above-normal precipitation was also increased relative to last month for northern portions of the West Coast due to support from C3S and CBaM guidance during JFM and FMA. Probabilities of below-normal precipitation for Southeast Alaska were reduced relative to last month due to lack of support from the majority of statistical and dynamical guidance.

As we progress further into Spring (MAM) through early Fall (SON), ENSO guidance becomes less coherent and trends are increasingly relied upon. A small area of residual enhanced above-normal precipitation probabilities indicated for parts of the northwestern CONUS during MAM disappears completely by AMJ. A northward migration of enhanced below normal-precipitation probabilities is forecast from MAM to July-August-September (JAS) across much of the West. This dry signal decreases in confidence heading into next Fall and disappears completely by next Winter. Farther to the east, the area of enhanced above-normal precipitation probabilities across the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley indicated in MAM migrates to the East Coast by early Summer and persists into early Fall, consistent with trends . Similar to JFM and FMA, increased chances of above-normal precipitation persist across northwestern Alaska and to varying degrees southward along the west coast of the Mainland from MAM through JJA. Thereafter, statistical guidance (including recent trends ) shifts the focus of increased above-normal precipitation probabilities to southeastern Alaska during next Summer and early Fall. Forecast confidence is generally low later in the Fall and next Winter with large areas of EC indicated. Weak tilts toward above-normal precipitation are generally indicated for small areas of the Pacific Northwest, much of coastal Alaska, and parts of eastern Interior Mainland Alaska during this period. Small areas of slightly enhanced above-normal precipitation probabilities are indicated for parts of the northern Plains, Southeast, and Ohio Valley next Winter. Conversely, weakly enhanced probabilities of below-normal precipitation are indicated for parts of the Southwest later next Winter.

Drought Outlook

| The yellow is the bad news and there is a lot of it. And there is a large area where drought is expected to persist. The area where drought is expected to improve is also large. With a La Nina winter ahead, Drought is likely to expand in parts of the Southern Tier of states. Overall the level of drought is expected to remain about the same with the increases and decreases being about equal. |

Short CPC Drought Discussion

Latest Seasonal Assessment – During the past month, widespread drought amelioration occurred across portions of northern Texas and northeastern New Mexico, extending northward to the upper Midwest. The onset of the wet season also eroded drought conditions across the Northwest, and an active pattern promoted drought relief across much of the central Appalachians and Corn Belt. Despite the widespread recharge, drought and abnormal dryness continued to blanket nearly three quarters of the contiguous United States as of the December 10, 2024 US Drought Monitor. La Ni�a conditions are favored to develop during the January – March period, though uncertainty continues regarding the strength of the midlatitude response, especially given the active intraseasonal signal anticipated to continue through January. The CPC monthly and seasonal outlooks favor a canonical La Nina response pattern, with drier conditions across the southern tier of the CONUS, a winter storm track favoring the Ohio Valley, Great Lakes, and interior New England, and an enhanced wet season for the Northwest. Therefore, further drought reduction is favored for the Northwest, along the Mississippi River Valley, and across the Great Lakes. Frozen streams and soil may slow the recharge of moisture across the upper Midwest and High Plains, as well as climatologically low precipitation amounts. Along the southern tier, drought development is possible for Arizona, portions of New Mexico, southern and eastern Texas, and the Southeast coastal plain. Despite the lack of a clear wet signal, a wet climatology and the potential for coastal systems makes gradual drought reduction the most likely outcome across the Northeast, though given the stark conditions at the onset of the winter season, some lingering drought is likely to persist through the end of March, and breaks in rainfall or low snow cover may result in re-development of drought during the Spring.

Drought conditions have expanded across Hawaii during the past few weeks due to subnormal rainfall. During the core wet season months of January through March, La Nina conditions typically favor increased rainfall across the islands, both due to enhanced trade winds and the potential for Kona Low events. Therefore, drought reduction is favored in this outlook. No drought conditions are currently present or favored to develop across Alaska, Puerto Rico, or the US Virgin Islands.

Looking out Four Seasons.

Twelve Temperature Maps. These are overlapping three-month maps (larger versions of these and other maps can be accessed HERE)

Notice that this presentation starts with Feb/March/April (FMA) since JFM is considered the near-term and is covered earlier in the presentation. The changes over time are generally discussed in the discussion but generally, you can see the changes easier in the maps. The discussion often provides the “why” and how the outlook might be different than what was issued last month.

Comparing the new outlook with the prior Outlook,

The easiest way to do the comparison is to print out both maps. If you have a color printer that is great but not needed. What I do is number the images from last month 1 – 12 starting with “1” and going left to right and then dropping down one row. Then for the new set of images, I number them 2 – 13. That is because one image from last month in the upper left is now discarded and a new image on the lower right is added. Once you get used to it, it is not difficult. In theory, the changes are discussed in the NOAA discussion but I usually find more changes. It is not necessarily important. I try to identify the changes but believe it would make this article overly long to enumerate them. The information is here for anyone who wishes to examine the changes. I comment below on some of the changes from the prior report by NOAA and important changes over time in the pattern.

| There has been a big change since last month starting in ASO 2025 with more of CONUS being EC rather than warmer than climatology. The explanation for this change in the NOAA discussion to me is incomplete at best. |

Similar to Temperature in terms of the organization of the twelve overlapping three-month outlooks.

Comparing the new outlook with the prior Outlook,

The maps that were released last month.

A good approach for doing this comparison is provided with the temperature discussion.

| The overall outlook is pretty much the same as last month. |

| It looks like we should be in La Nina any day now. This type of graphic does not show how strong an El Nino or a La Nina is likely to be. What is forecast is a La Nina, which if it does occur, most likely will not be stronger than a marginal La Nina. |

IRI at Columbia University Published this today.

| IRI has a contract with NOAA and published this today. Apparently, NOAA had this earlier and used it. The plume shows the results of models run by many organizations that run models. `The thick red line is the average of the models that use dynamic modeling (which NOAA usually prefers) and the thick green line is the average of the statistical models which probably are better for distant forecasts than dynamic models but less good for near-term forecasts. I show this to inform readers that weather forecasting is difficult and this is just about ENSO and that is among the more reliable forecasts. |

Resources

Other Reports and Information

The Wildfire Report can be accessed HERE

–

| I hope you found this article interesting and useful. |

–