Global Warming and Population Growth, create a need for more water.

There are a number of different ways to address a shortage of water:

-

Get equal value from less water (Conservation)

-

Find more water from surface and groundwater sources

-

Have more precipitation (Increase the velocity of water)

We previously addressed (2) based on an excellent presentation by an expert in that area. We will discuss conservation in the future, particularly with respect to agriculture. There are major opportunities to achieve increased water use efficiency in agriculture.

In this article, we discuss “Finding More Water by Using Cloud Seeding to Increase Precipitation”.

Recently I published an article on using cloud seeding to increase precipitation. It is included (with some updates) in it’s entirety in Part II of this article. But to define what we are talking about the next two images are important.

| Weather modification with cloud seeding was discovered by General Electric at the Schenectady New York Laboratory. Initially, on July 14, 1946, they used Dry Ice. Of course, prior to that time, there were other attempts at increasing precipitation. The science is discussed in Part II of this article but the general approach is to assist clouds in converting the moisture in clouds to become snow (or in the tropics large raindrops) so that in both cases they are heavy enough to fall from the clouds to the ground. Importantly, precipitation in general soon returns to the atmosphere so the water molecules are available to precipitate again and again. Cloud seeding speeds up the process slightly. |

| Cloud seeding can be used for three different purposes: Precipitation enhancement, hail suppression, and fog dispersal. In this prior article, I focused on precipitation enhancement. The discussion in Part I of this article would apply to all three purposes and most projects of any sort since it is general economic theory. |

Part I

In this new article, I want to discuss the economics of cloud seeding to increase precipitation. For a proposed cloud seeding project it is important to know whether or not it is economically justifiable and if implemented continues to be economically justified. We discussed that to some extent in the earlier article which is included in Part II of this article. We know that where conditions are appropriate, cloud seeding can increase the precipitation over what is called the target area. The reason for this is that natural precipitation processes are very inefficient. That is why precipitation occurs in many parts of the world that are many miles from the source of the moisture that is in the atmosphere. The atmosphere can hold a lot of water.

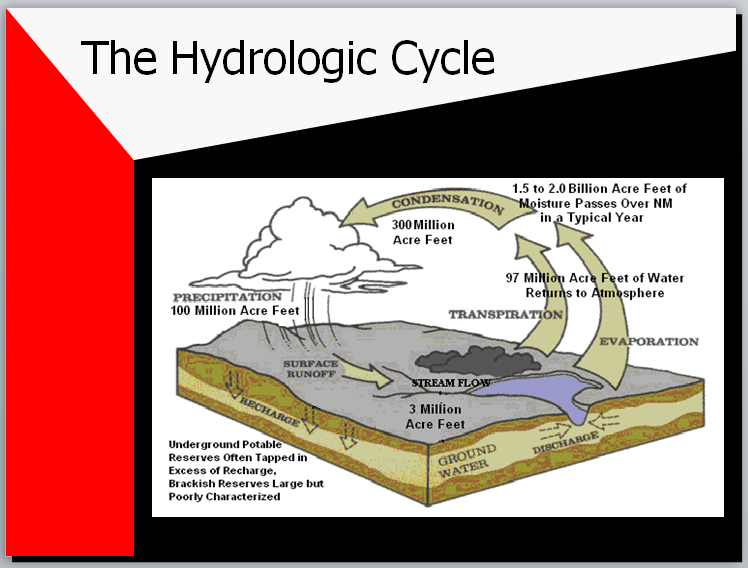

Hydrologic Cycle

It is important to remember that water is a compound that is almost impossible to destroy. States view the consumption of water in agriculture as a depletion of the state’s water resource but evaporation and transpiration of plants in the process of photosynthesis returns the water to the atmosphere where it can precipitate and benefit others in the same state or other states or other nations. This can be repeated over and over again. Precipitation over oceans or water run-off into oceans makes that water unusable {other than importantly marine life) unless it is purified. However, the water is not destroyed and can be recovered and used (usually in arid areas like Israel). Most of our precipitation comes from clouds that form over large bodies of water. So it is best to view all of this as a hydrologic cycle. Moisture evaporating from bodies of water or the ground or from plants enters the atmosphere. Under certain conditions moisture forms clouds. Again, under certain conditions, some of the moisture in clouds precipitates. Precipitation often provides value to people and the environment but mostly (groundwater is an exception that we do not cover in this article) rather quickly returns to the atmosphere to provide the moisture necessary to form clouds and another round of precipitation. This is a process that is called the “hydrologic cycle”.

Velocity of the Hydrologic Cycle

Cloud seeding speeds up the process which means that individual molecules of water end up providing benefits more times in a year. This process is not widely understood by the general public. In a way, it is analogous to the money supply. If there is more economic activity. For simplicity consider a situation where printed currency is the only form of money. When the economy is good, a given unit of currency (for example a one-dollar bill) will pass through the hands of more people than when the economy is less good. So increasing the velocity of money is often a good thing. Within narrow limits, we can increase the velocity of the hydrologic cycle and increase the contribution of water to society.

Selection of cloud seeding projects

We know that we can increase the process of precipitation from clouds and the water being used or wasted but either way returning to the atmosphere to precipitate somewhere else. The questions addressed in this article are when is the effort to do this both economical and easily recognized as being economical?

Some information on my background

Years ago, I taught a graduate-level course in Engineering Economics. The focus of the course was applications in information systems but the theory is the same for any endeavor. I did not wish to teach this course but the Vice President of the consulting firm from which I derived most of my income was also the Dean of the Management School of a significant educational entity (which is now part of NYU) and he insisted that I teach this course (based on my educational background and much experience with doing economic analysis) and I pretty much had no choice but to do so. I enjoyed it but it meant that most of Friday and Saturday every other week was tied up traveling to a neighboring state to teach this course. Teaching the course made me realize that what is basic microeconomic theory is difficult for many people involved in technology development to comprehend.

So it is with some trepidation that I address the topic in this article.

Economic analysis of potential and operational cloud seeding projects

Generally, projects that do not produce more value than the cost are non-economic. I will not address the exceptions to this rule because it devolves into a semantic issue of how one defines value.

But even if the approach produces more value than the cost you still have to look at:

- Who benefits and

- Who pays

If the payor and beneficiary are different, there can be problems. [In healthcare it is even more difficult because there is usually a third party involved i.e. the insurance company. That creates a very complicated situation which I addressed in a project done for the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. There are some aspects of that three-way situation with cloud seeding also.]

There can be other factors which complicate the analysis. This is especially pertinent in the U.S. West where most cloud seeding takes place. In most cases, the allocation of the water supply is based on the Priority Doctrine (PD). This means that with cloud seeding, the identity of the beneficiary is often not known. If more water is available it goes to those who otherwise would not receive water because their priority would not have been high enough. Priority is usually determined by who put the water to use first. That may not seem to be an optimal way to do things but it tends to avoid violence since it is easier to determine who put the water to use first than to agree on which uses are better for society than other uses.

Often there is an exception namely that precipitation that falls on your land can be used by the land owner or the land owner’s designated (typically a renter of the land) as long as the water does not leave the boundaries of the property. If it leaves the property it typically enters the public water supply and the Priority Doctrine takes over. However, the specific rules vary by state in the U.S.

A further complication is what are called interstate river compacts which are agreements among states concerning the distribution of the available water supply. The reason this is important concerning cloud seeding is the beneficiary may be in another state. Two important interstate river compacts are the Colorado River Compact and the Rio Grande River Compact. Both of these also have delivery requirements to Mexico. There are many other interstate river compacts. In general, each one has its own rules.

Thus there are two major categories of beneficiaries:

a. A beneficiary who puts the additional water to beneficial use

b. A governmental entity that is obligated to deliver water downstream for the benefit of other beneficiaries. This can be considered an indirect beneficiary or a facilitator.

Looking at things from a different perspective the major beneficiaries of water are:

- Farmers

- Ranchers

- Municipalities especially with regard to their need to deliver water to people and for other uses within a municipality

- Ski resorts (they need snow that falls from clouds or water to make snow

- Hydroelectric facilities to generate electricity.

- Commercial and industrial users who are not getting their water delivered to them by municipalities.

- Recreation

- The environment

Some of the above consume the water and others simply use it and pass it on (hydroelectric and ski resorts). For those who from a legal perspective consume water, that water generally returns to the atmosphere or is treated and reused. So our use of language can be somewhat inconsistent with science when it comes to water.

Implications

In some cases, the payor/funder of a cloud seeding project is also the beneficiary. That is the simple case since the payor can decide if the cost is worth the benefit.

In many cases, the payor of a cloud seeding project is an indirect beneficiary. That is often the case with the interstate river compacts and it is generally difficult to get projects funded that assist states in meeting their compact obligations.

Further Discussion

The economics of cloud seeding are complicated. One way of looking at this is that cloud seeding often resembles infrastructure. When a road or bridge is built it usually is not clear exactly who will benefit. Generally, the consideration is whether or not the community or state or the U.S. will benefit. If funded with tax money (or borrowing which usually translates into property taxes) some will have paid for something that does not benefit them but others, and some will benefit many times more than their taxes.

In many cases, cloud seeding is like that. But in some cases, the direct beneficiary can be identified. Perhaps the best example of that would be ski resorts. They benefit from more snow falling from clouds thus having to make less snow. Hydroelectric in some cases is much like the ski resort example. The hydroelectric utility or the users of the electricity generated benefit and they can often recognize the value of cloud seeding to increase the generation of electricity. But on the Colorado River, it is often unclear who would be the beneficiary of more cloud seeding since there are so many different beneficiaries of there being more water in the river. A special case is when the delivery requirements of the interstate river compact are not being met and the two alternatives are to find more water or use less water.

So there is often a combination of private and public funding of cloud seeding. As a general rule, the greater the distance of the cloud seeding project from the beneficiaries the more difficult it is to have taxpayers or local government entities see the value to them of such a cloud seeding project.

The Prior Article which explains Cloud Seeding now follows as Part II.

Some will need to click on “Read More” to access the full article.

Part II

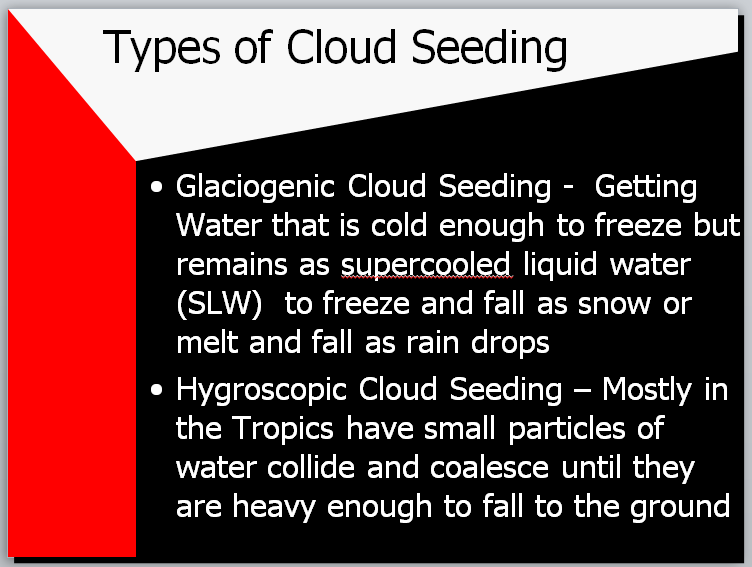

| In this article, I am talking about only Glaciogenic cloud seeding which can be winter/mountain-based or summer/Great Plains-based. |

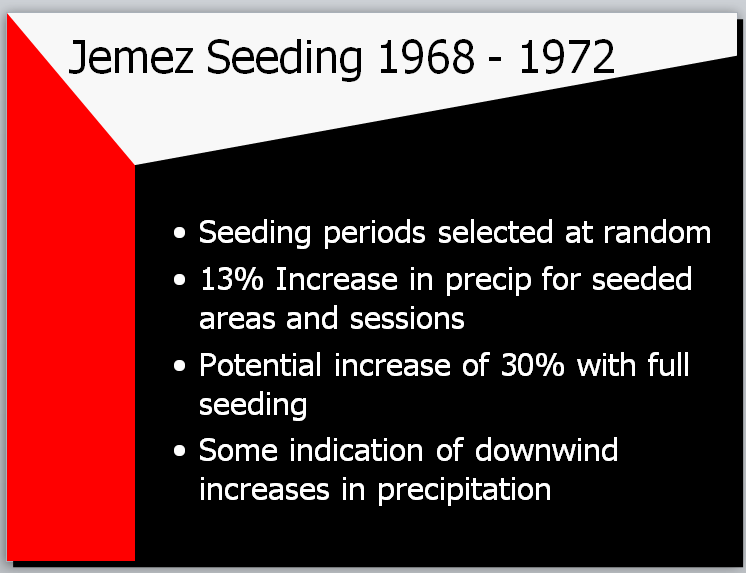

Many states are active with cloud seeding projects. It has lagged in New Mexico even though the initial interest in the West began in New Mexico. But the effort got a boost in the period below when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation funded a research project (Skywater LINK) in I believe three states, one of which was New Mexico.

| The above is a short summary of the results of that research project for the part that was conducted in New Mexico. |

| Global warming has changed the pattern of precipitation less in some places and more in other places. Higher temperatures result in more evaporative losses and plants generally grow faster when it is warmer and carbon dioxide levels are higher. So many places need more water. |

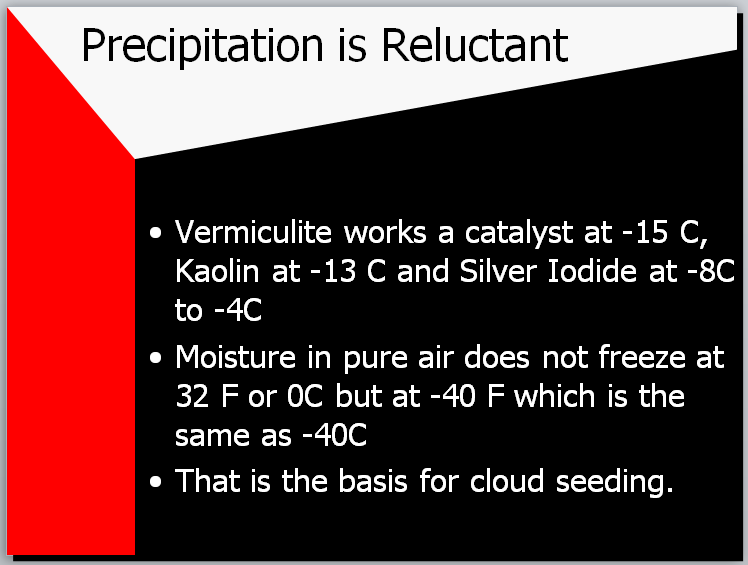

| In the atmosphere, water does not always freeze at 32F and 0C. In some air masses, there are many small droplets that are not heavy enough to fall to the ground. For summer clouds the updrafts may not be strong enough for the cloud to grow. |

| The simplest way to look at glaciogenic cloud seeding is that it helps water freeze into snowflakes which can land as snow or melt on the way down. |

| The general idea is for nature to move moisture-bearing airmasses higher, cool and then assist them in glaciation. |

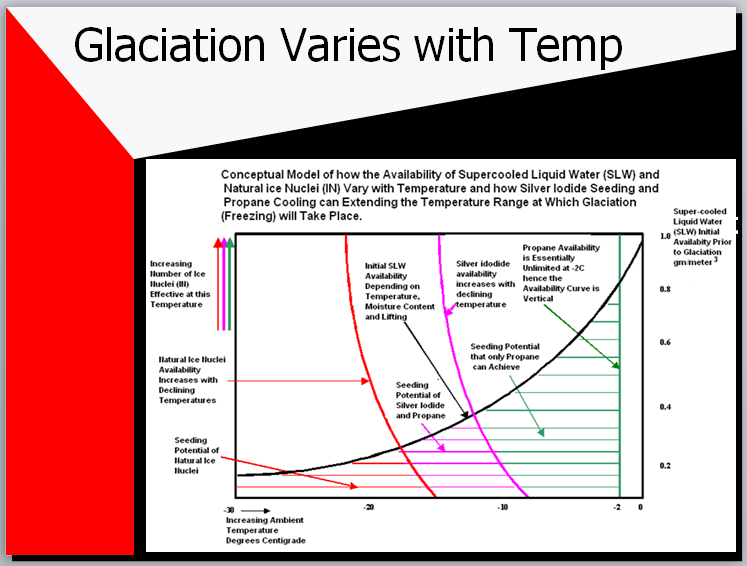

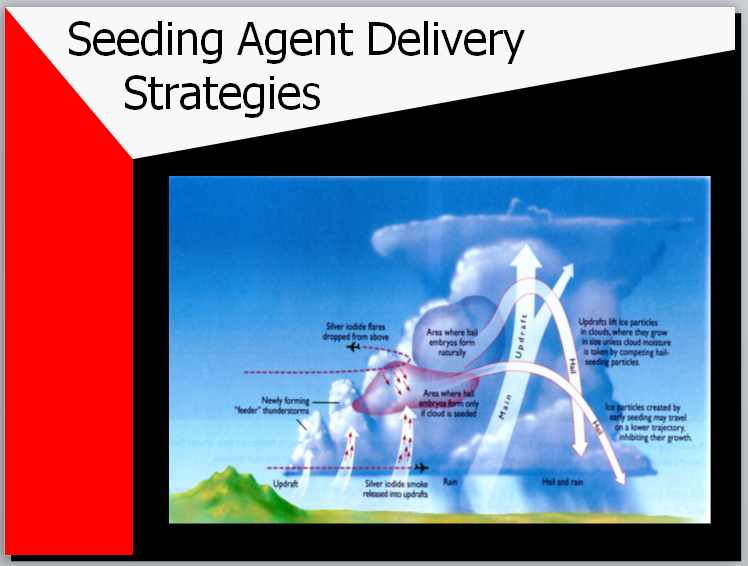

| I worked with Dr. James Heimbach Jr. (now deceased) to create this graphic which shows that colder temperatures activate particles that participate in glaciating moisture. So not only do mountains force air masses to rise and cool but that process also activates particles that serve as ice nuclei. |

| You need moisture-rich clouds and for many reasons, you can only seed small areas so the impact of cloud seeding which is nominally a 10% increase in precipitation, impacts only a limited part of the weather patterns that produce rain and snow. |

| The second bullet point is very important. If you seed the Rocky Mountains and someone downstream who is dependent on Colorado River water has more water due to the cloud seeding in the Rocky Mountains, they may not realize that the cloud seeding provided them with more water. |

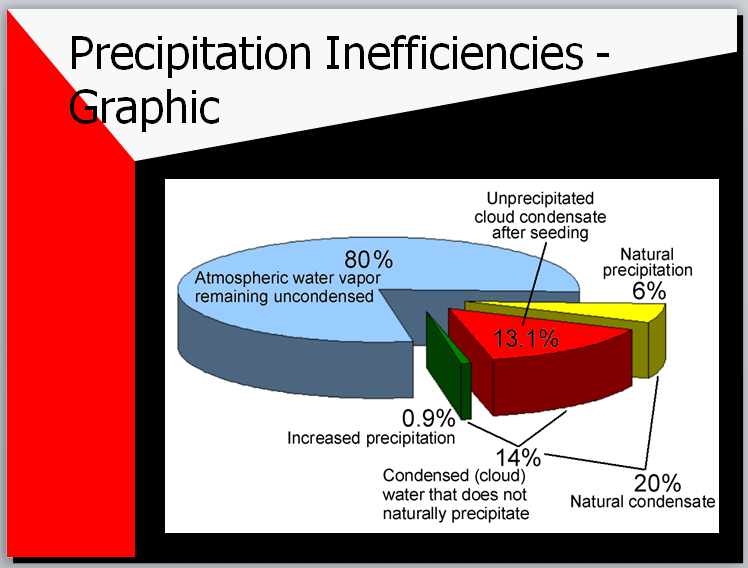

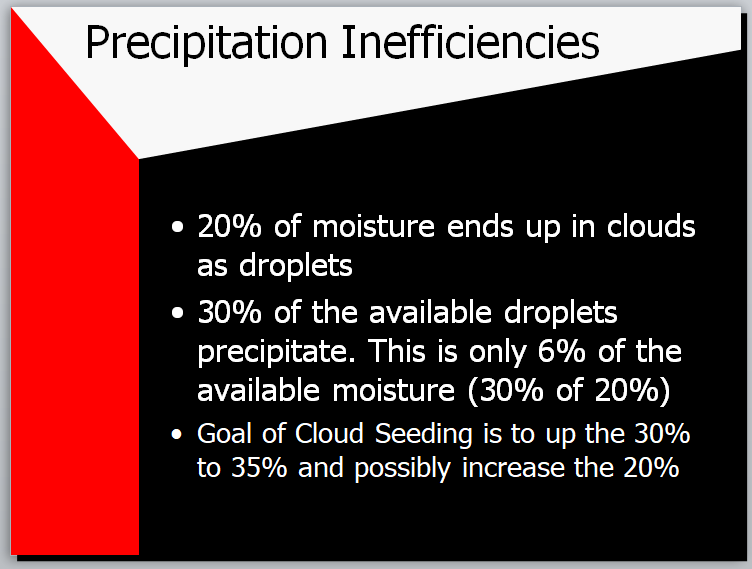

| We cover this more in the next slide and I do not have a reference to the size of the sections of the pie but most moisture just transits states. Some part forms clouds and some of the moisture in the clouds precipitates and actually reaches the ground. |

| I had a reference for this data as it applied to Colorado but I can not find it so considered it to be representative. The point is that only a small percentage of the moisture in the atmosphere falls as snow or rain. If that percentage can be increased just a bit it creates a lot of water. |

| This graphic is a modification of the work of B. Hove of the North Dakota State Water Commission. I modified it to represent the situation in New Mexico. The solid number is the 100 million acre-feet of precipitation in an average year. Some of that water recharges aquifers. About 2,000,000 acre-feet enters the water supply. Some water evaporates or sustains plant life (transpiration) in remote areas. What is important is that other than aquifer recharge, all water quickly returns to the atmosphere. I call this the hydrologic circle. As explained earlier, the best information I have calculated, which should be considered a guess since I can not find the study that determined this is that to have 100 millon acre-feet of precipitation you probably need about 300 MM af of water in clouds and that might mean that 1.5 to 2 Billion acre-feet of moisture passes over New Mexico. The speed at which this happens I call the velocity of water much like the concept in the monetary system of the U.S. So I see cloud seeding as a way to increase the velocity of water and have more uses of each molecule of water in a year.

Water is almost impossible to destroy so using it in one place does not reduce the amount of water available to the east. |

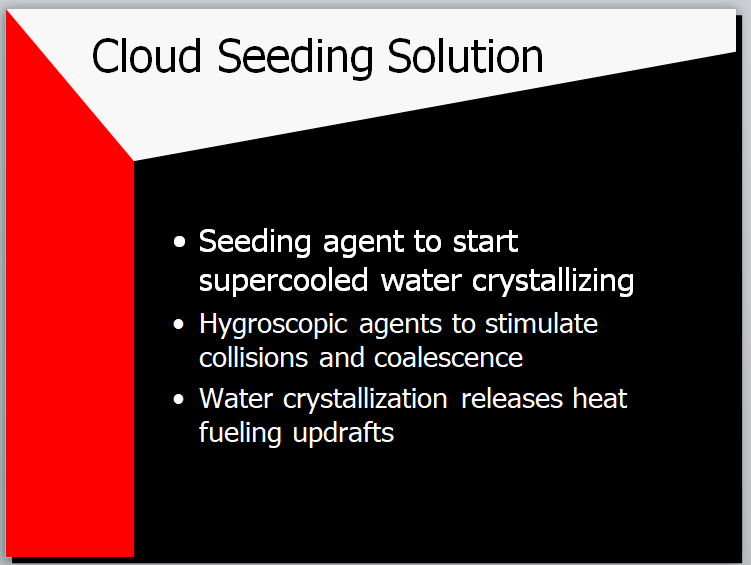

| We do mostly glaciogenic seeding in the U.S. mostly with silver iodide and sometimes with dry ice. But often a hygroscopic agent is added just in case there is some tropic air mixed in. The stimulation of updrafts occurs with all clouds but is more significant for summer clouds and it extends the life of the cloud. |

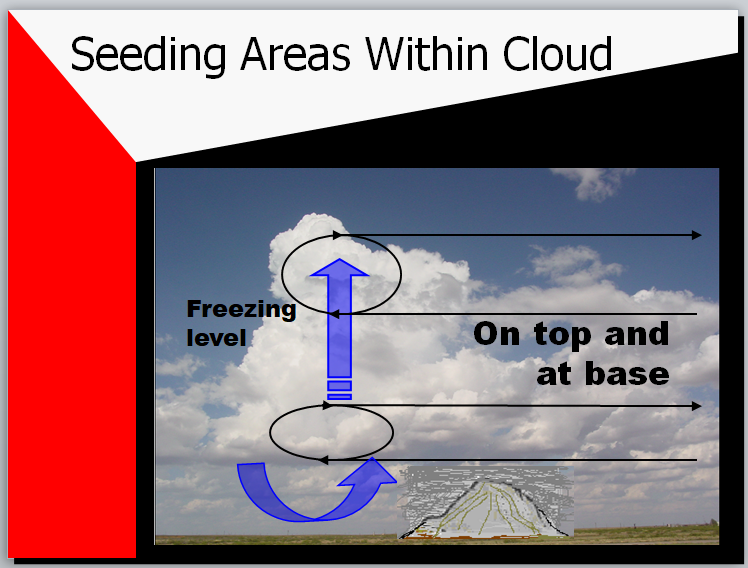

| This is mostly about summer seeding on the Great Plains with aircraft. These types of clouds when precipitation is stimulated can actually grow in size since freezing releases heat (how many remember High School Chemistry? |

| A more elaborate explanation of summer clouds and seeding with aircraft |

| For winter seeding which is more common, the silver iodide is burned in acetone to form smoke which rises to meet the SLW in clouds. It is a very small amount of silver iodide because of Avagadro’s Number. (Avogadro’s number is the number of particles in 1 mole of a substance). It is a large number. The goal is to have the ground-based generator create that number of silver Iodide particles so the quality of the ground-based generator is important. Also, it is better to have remote-controlled ground-based generators than manually operated ground-based generators. There are many considerations which determine the level of success of a project. |

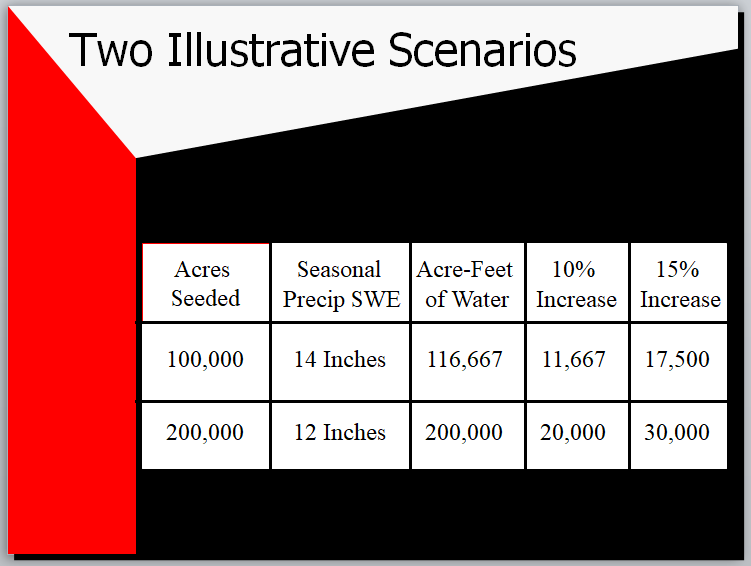

| New Mexico has about a 2,000,000 acre feet water budget. The above are two potential projects. New Mexico is pretty arid but cloud seeding is done in the mountains so there is more than average precipitation at elevation during the winter seeding. The second example is for an area of about 10 miles wide and 20 miles long. The result would be perhaps an additional 30,000 acre-feet of water which is small compared to 2,000,000 but still a significant amount of water.

30,000 acre-feet of water is enough water for 120,000 families or perhaps a bit more. It is also enough for close to 15,000 acres of farm land. |

| The above does not show the cost but the value is enough for a very high ROI |

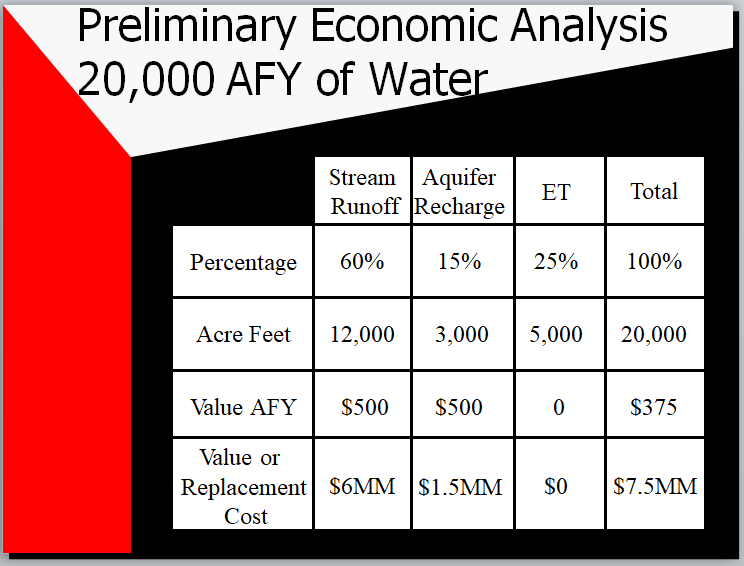

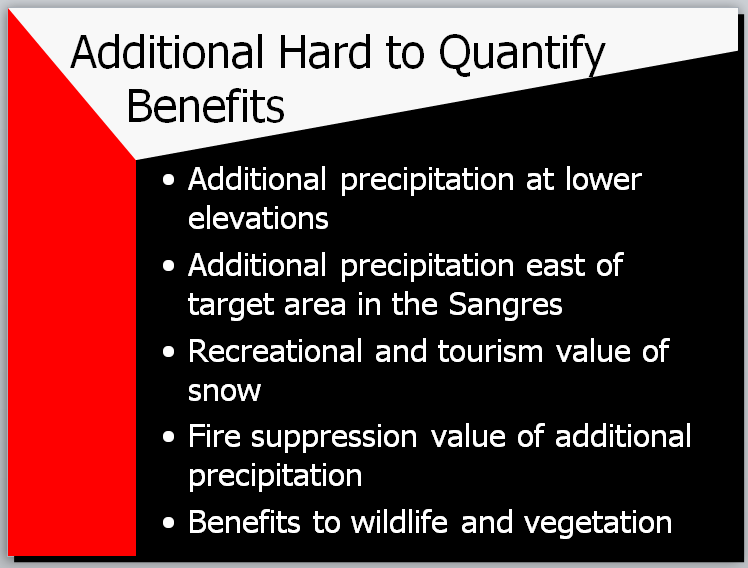

| The above is specific to a particular proposed project. The primary goal of most cloud seeding projects is to generate additional stream flow. But there are many other benefits of more precipitation. |

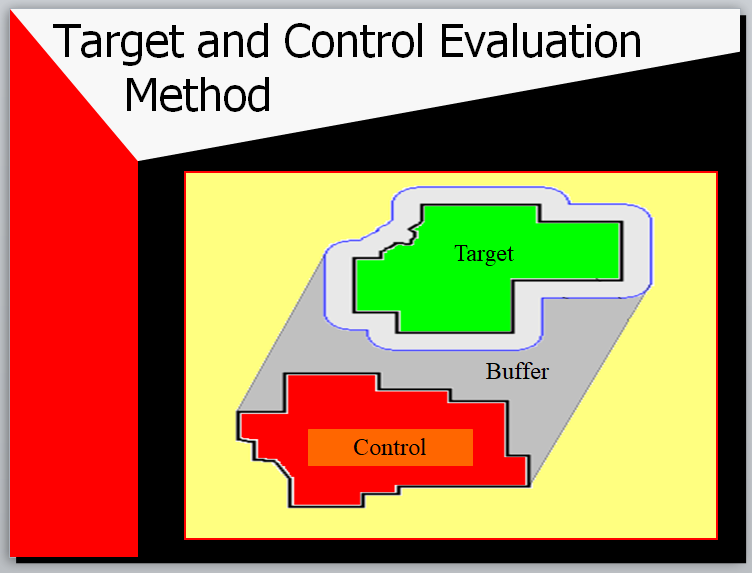

| Here we are discussing the effectiveness of cloud seeding. The most used method is called target and control. The target area is where the seeding would take place. The control area is an area where historically there is a predictable ratio of precipitation (mostly snow in one area as compared to the target area.

You seed the target area. The actual snow in the control area lets you calculate how much snow (water equivalent) you would expect in the target area. The difference between the actual and the calculated if positive is the benefit of cloud seeding. If negative it is a negative impact of cloud seeding. One can do the same with a target stream and a control stream. |

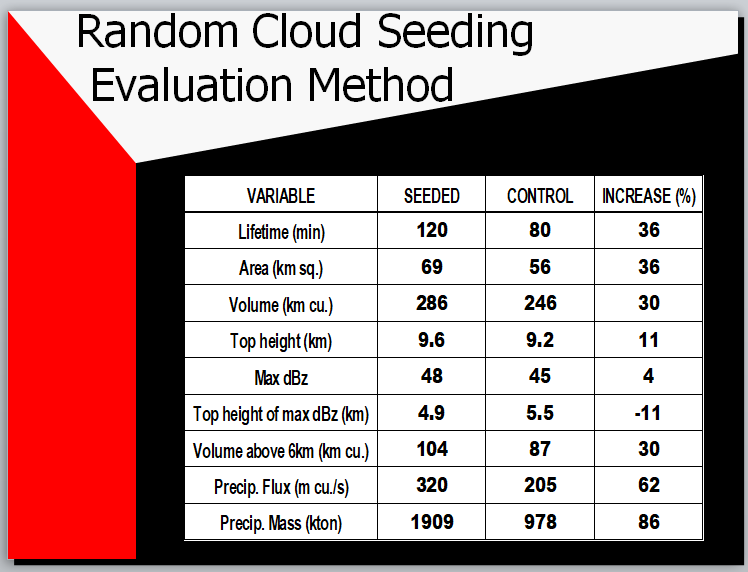

| This is a summer seeding assessment. In theory, they pick two identical clouds and flip a coin to see which one they seed. With radar and software, they are able to estimate the parameters shown. Of most interest is the precipitation flux which is how much moisture left the cloud. It may not all have reached the ground. Unlike winter seeding which has modest but important increases in snow, summer seeding for the ideal clouds produces a large increase in precipitation. The problem is getting to the ideal clouds in time. Also of interest is the seed summer clouds last longer. |

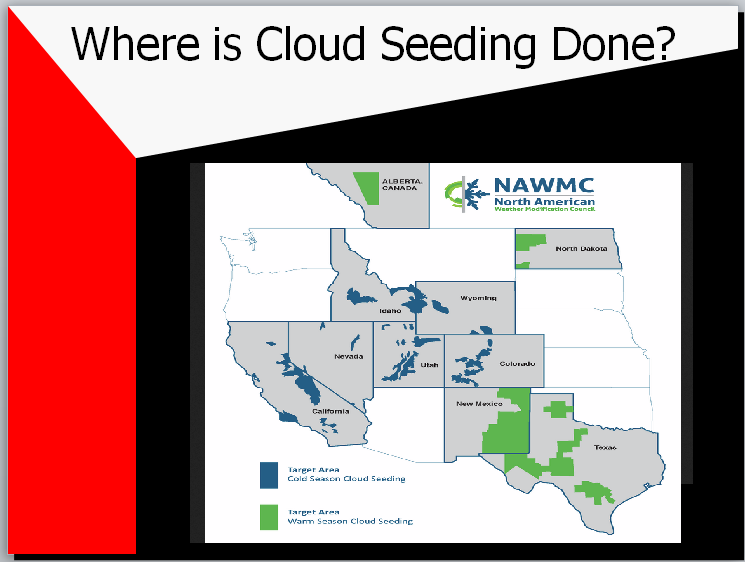

| The map is courtesy of the NAWMC. There are a lot of cloud seeding projects. I expect the number of projects will slowly increase but the conditions that make for a successful cloud seeding project do not exist everywhere. |

Additional Reading

Weather Modification Association LINK

North American Weather Modification Association LINK

ASCE EWRI Weather Modification Standards and Guidance Manuals LINK

| I hope you found this article interesting and useful. |