On the third Thursday of the month right on schedule NOAA issued their updated Seasonal Outlook which I describe as their Four-Season Outlook because it extends a bit more than one year into the future. The information released also included the Mid-Month Outlook for the following month plus the weather and drought outlook for the next three months. I present the information issued by NOAA and try to add context to it. It is quite a challenge for NOAA to address the subsequent month, the subsequent three-month period as well as the twelve successive three-month periods for a year or a bit more.

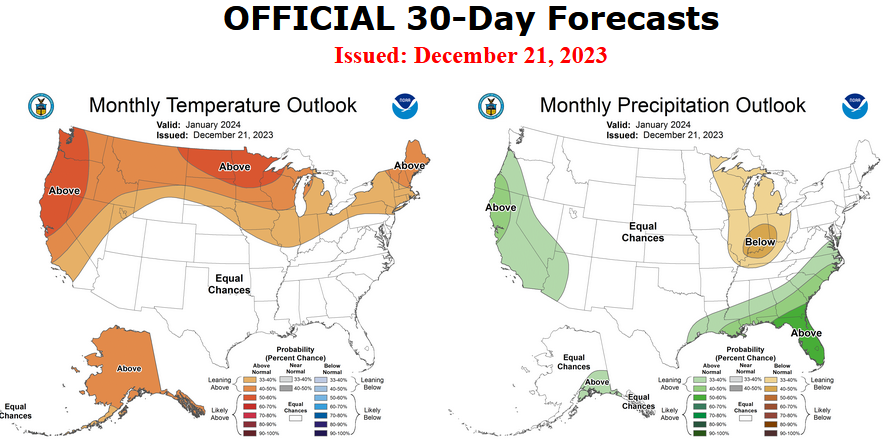

First, Let’s Take a Look at the (mid-month) Outlook for January.

It will be updated on the last day of December which is soon because the third Thursday of this month occurred at the latest time possible because December 1 the first day of the month was a Monday.

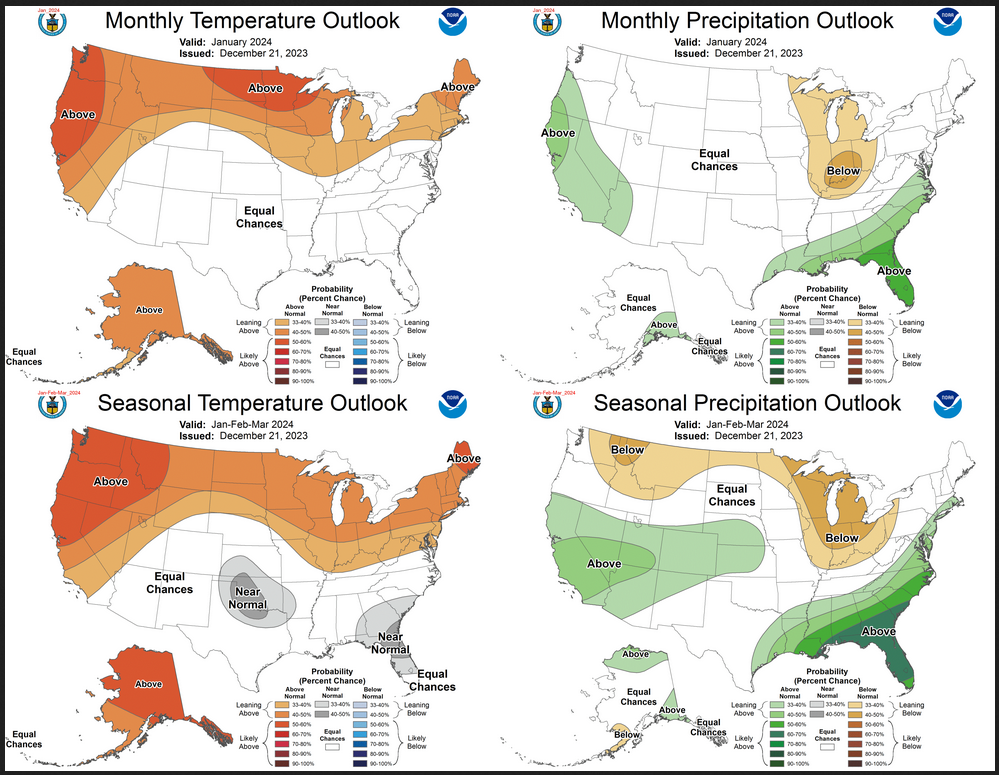

Then I present a graphic that shows both the preliminary Outlook for December and the three-month outlook for DJF 2023-2024. So you get the full picture in one graphic. For some, that may be all they are interested in. Others will be interested in the longer-term predictions and also the rationale supporting the predictions which is mostly provided by the NOAA discussion.

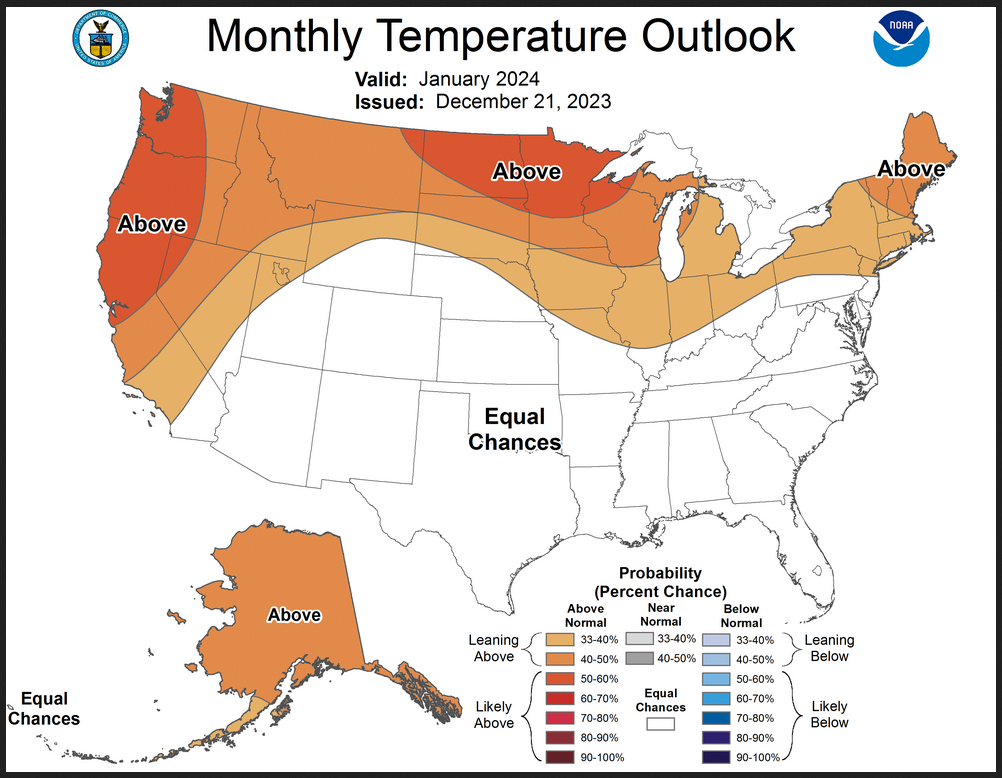

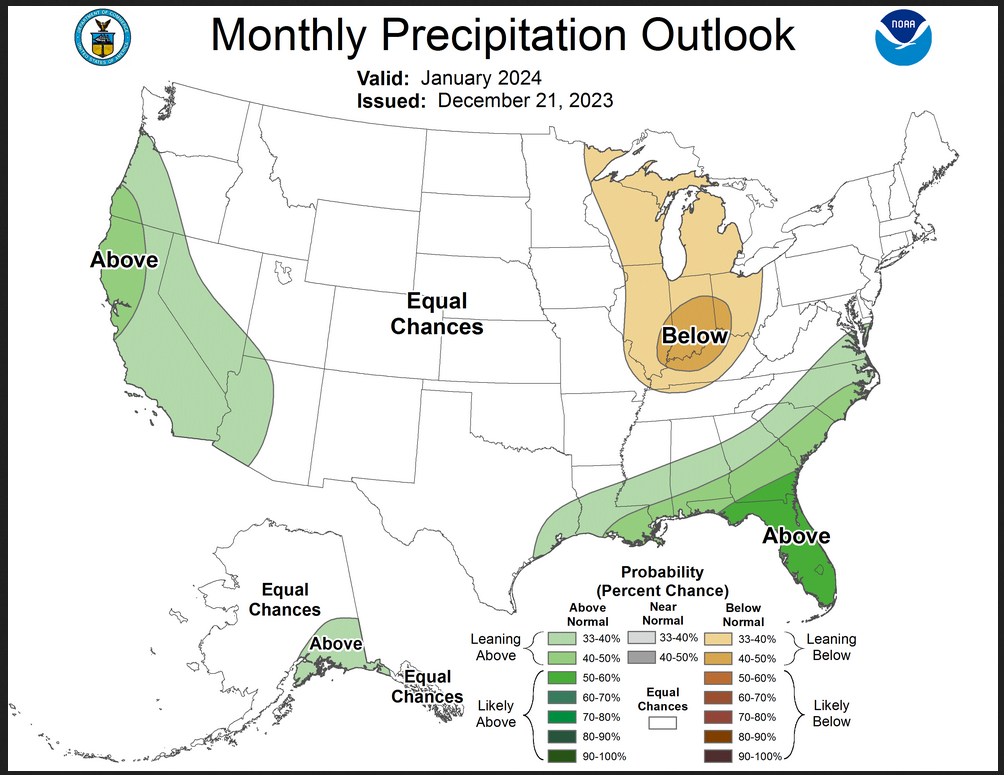

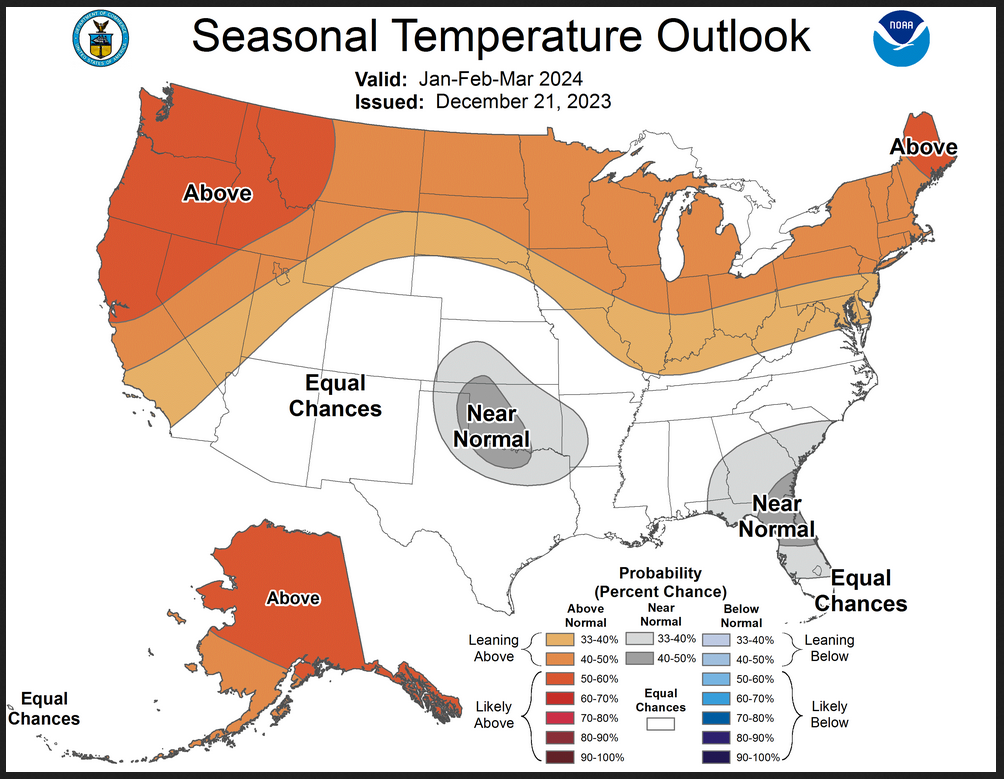

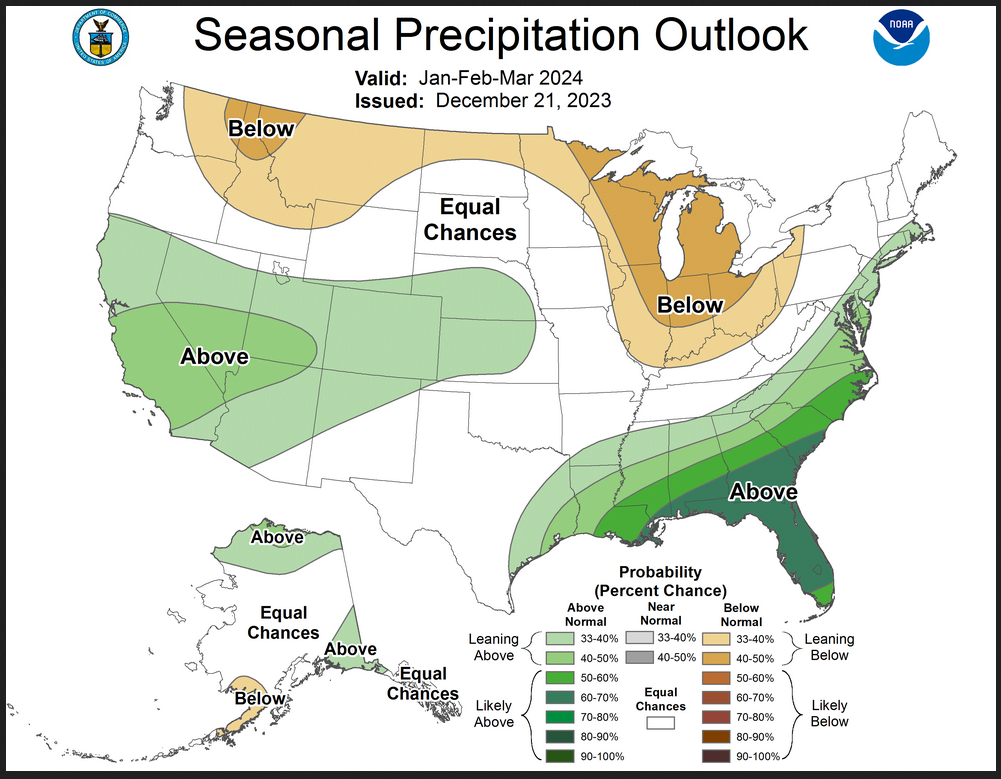

The top row is what is now called the Mid-Month Outlook for next month which will be updated at the end of this month. There is a temperature map and a precipitation map. The second row is a three-month outlook that includes next month. I think the outlook maps are self-explanatory. What is important to remember is that they show deviations from the current definition of normal which is the period 1991 through 2020. So this is not a forecast of the absolute value of temperature or precipitation but the change from what is defined as normal or to use the technical term “climatology”.

| Notice that the outlook for next month and the three-month outlooks are somewhat different, particularly with respect to precipitation. This tells us that February and March will be different than January to some extent. |

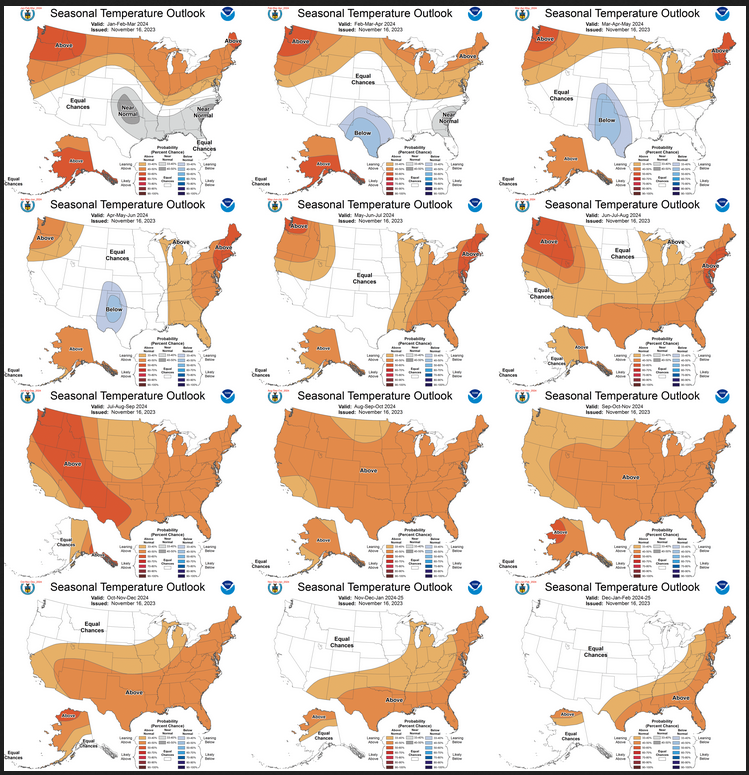

The full NOAA Seasonal Outlook extends through January/February/March of 2025. All of these maps are in the body of the article. Large maps are there for January and the three-month period Jan/Feb/Mar. Small maps are provided beyond that through March of 2025 with a link to get larger versions of these maps.

NOAA provides an excellent discussion to support the maps. It is included in the body of this report. In some cases, one will need to click on “read more” to read the full article. For those on my email list where I have sent the url of the article, that will not be necessary.

Here are larger versions of the Temperature and Precipitation Outlook maps for next month.

The maps are pretty clear in terms of the outlook.

And here are large versions of the three-month JFM 2024 Outlook

First temperature followed by precipitation.

| These maps are larger versions of what was shown earlier. |

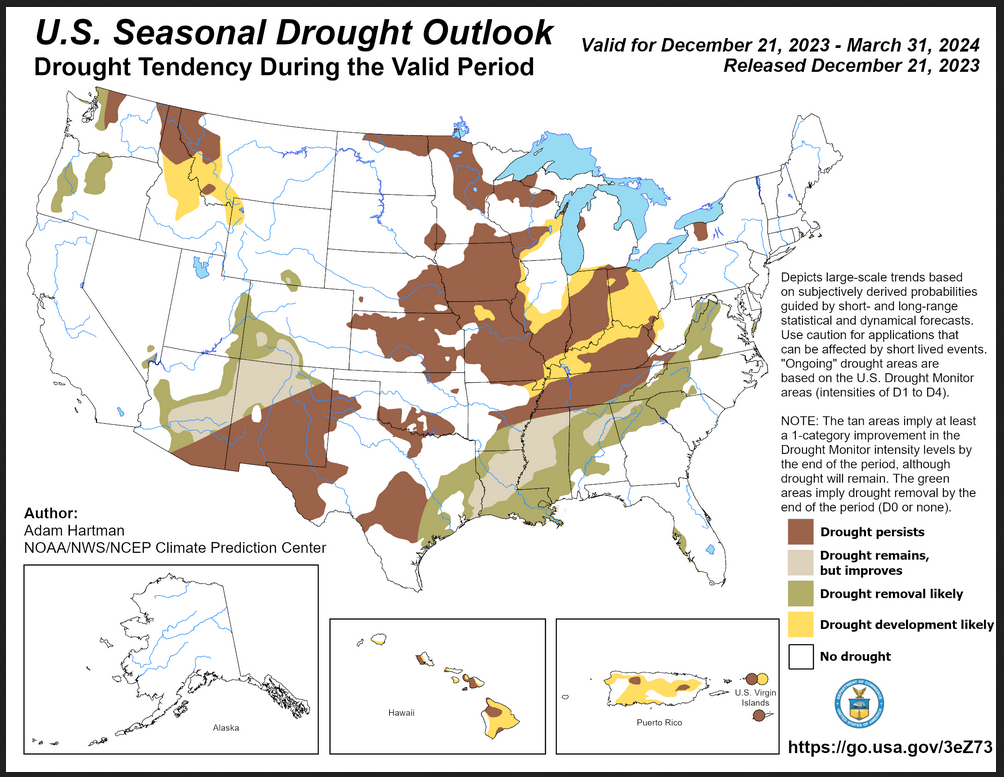

Drought Outlook

| The yellow is the bad news and there is some of that. There is a large area where drought removal or lessening is likely to happen plus there is a large area where drought is expected to persist. Overall the level of drought is expected to decline. There is concern about the situation for next year’s crop as we move into Spring. |

Short CPC Drought Discussion

Latest Seasonal Assessment – Since the December-February Seasonal Drought Outlook (SDO) released in mid-November, drought has slowly improved across parts of the Pacific Northwest, Southern Plains, and southeastern contiguous U.S. (CONUS), aided by persistent Pacific flow into the northwestern CONUS and an active storm track across the southern tier of the lower 48 states. Conversely, drought expansion and intensification was prominent across parts of the Middle Mississippi and Ohio Valleys, where short-term precipitation deficits continued to mount and temperatures have been running more than 5 degrees above normal since the start of December. Looking ahead to the January-February-March (JFM) SDO, El Niño is forecast to make its presence known, favoring a continuation of improving drought conditions across parts of the southern CONUS and extending into the Mid-Atlantic. However, uncertainty in the temperature and precipitation outlooks across portions of the central CONUS from the Southern Plains northeastward to the Middle Mississippi and Ohio Valleys favors widespread drought persistence. JFM is also a drier time of year for most of these areas. Drought development is forecast for parts of the Corn Belt and Ohio Valley, where odds for above normal temperatures and below normal precipitation increase in the Great Lakes vicinity. Drought persistence is also favored across parts of the Northern Plains and Upper Midwest through the end of March, where the ground is expected to remain frozen for much of the season, locking soil moisture in place for many areas.

Alaska is forecast to remain drought-free through the end of March, with wet antecedent conditions and favorable precipitation outlooks. Conversely, antecedent dryness, El Niño, and unfavorable precipitation and temperature outlooks favor drought persistence and development in Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

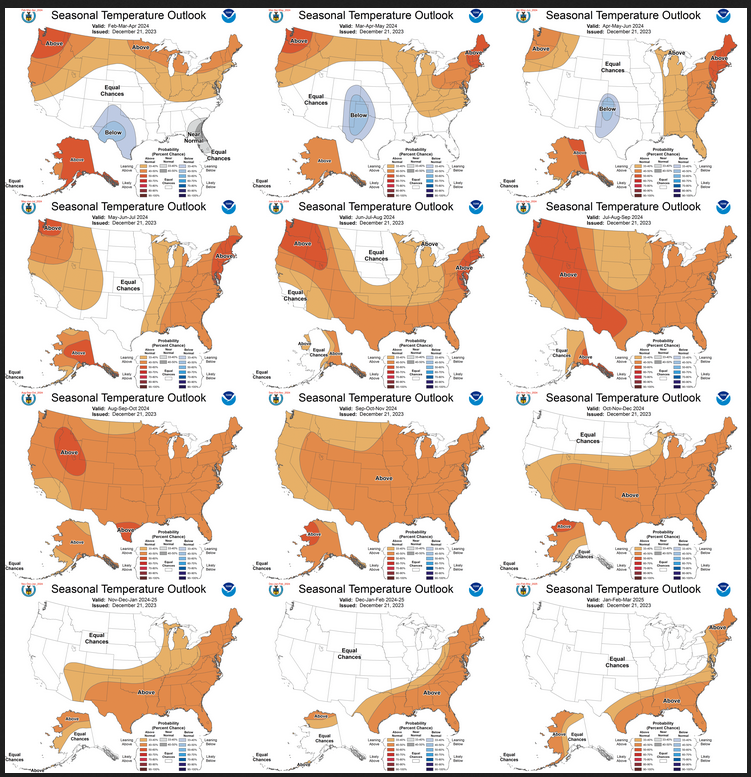

Looking out Four Seasons.

Twelve Temperature Maps. These are overlapping three-month maps (larger versions of these and other maps can be accessed HERE)

Notice that this presentation starts with January/February/March 2024 (JFM) since DJF is considered the near-term and is covered earlier in the presentation. The changes over time are generally discussed in the discussion but you can see the changes easier in the maps.

Comparing the new outlook with the prior Outlook,

The 12 temperature maps were issued last month.

The easiest way to do the comparison is to print out both maps. If you have a color printer that is great but not needed. What I do is number the images from last month 1 – 12 starting with “1” and going left to right and then dropping down one row. Then for the new set of images, I number them 2 – 13. That is because one image from last month in the upper left is now discarded and a new image on the lower right is added. Once you get used to it, it is not difficult. In theory, the changes are discussed in the NOAA discussion but I usually find more changes. It is not necessarily important. I try to identify the changes but believe it would make this article overly long to enumerate them. The information is here for anyone who wishes to examine the changes. I comment below on some of the changes from the prior report by NOAA and important changes over time in the pattern.

| Changes for JFM 2024 are mentioned in the NOAA discussion. I will take a closer look at these maps when I get up but so far I do not see a lot of change. |

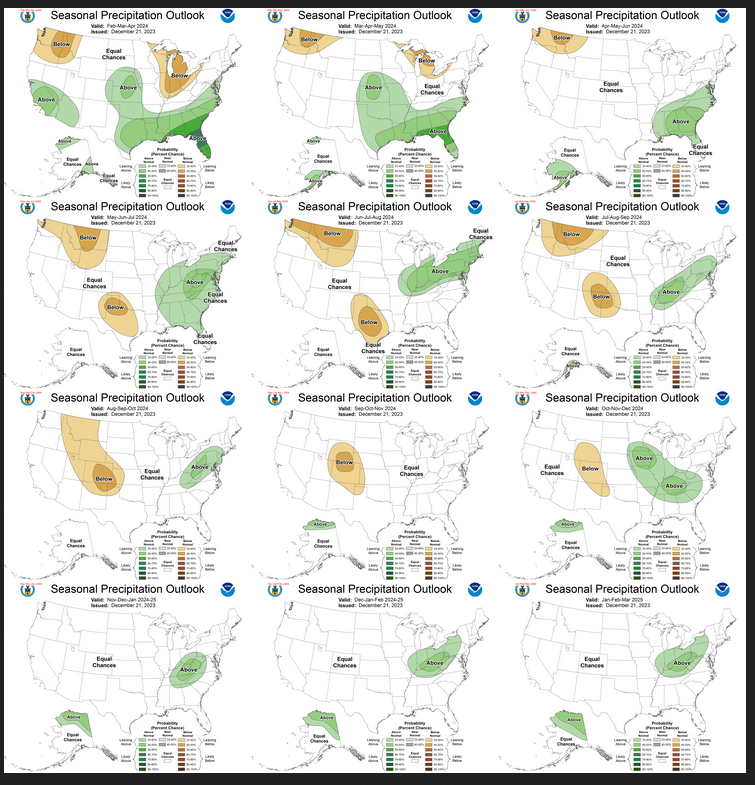

Now the Twelve New Precipitation Maps

Similar to Temperature in terms of the organization of the twelve overlapping three-month outlooks.

Comparing the new outlook with the prior Outlook,

The maps that were released last month.

A good approach for doing this comparison is provided with the temperature discussion.

| Changes for JFM 2024 are mentioned in the NOAA discussion. I will take a closer look at these maps when I get up but so far I do not see a lot of change. |

NOAA Discussion

Maps tell a story but to really understand what is going you need to read the discussion. I combine the 30-day discussion with the long-term discussion and rearrange it a bit and add a few additional titles (where they are not all caps the titles are my additions). Readers may also wish to take a look at the article we published last week on the NOAA ENSO forecast. That can be accessed here.

I will use bold type to highlight some things that are especially important. My comments, if any, are enclosed in brackets [ ].

CURRENT ATMOSPHERIC AND OCEANIC CONDITIONS

El Niño conditions are observed in both the atmosphere and ocean. In the last 4 weeks, equatorial SSTs were above average across most of the Pacific Ocean and near-average in the western Pacific Ocean. Above-average SSTs strengthened in the Central Equatorial Pacific but cooled in extratropical Pacific near the Date Line. SST anomalies over the recent week were 1.5 degrees C in the Niño1+2 region, and 2.0 degrees C in the Niño 3.4 region.

Upper ocean heat anomalies for 180-100 degrees West have been decreased from mid-November into mid-December, but remain among the highest levels observed in 2023. Positive (negative) subsurface temperature anomalies dominate much of the equatorial Pacific Ocean east (west) of the Date Line, with little change to the anomalies amplitude in the early parts of December. The above normal subsurface temperatures support persistence of the El Niño event.

Positive Outgoing Longwave Radiation (OLR) anomalies (suppressed convection and precipitation) were evident around Indonesia. Negative OLR anomalies (enhanced convection and precipitation) were observed around the Date Line, and extend into the eastern Pacific, remaining just north of the equator. Low-level (850-hPa) wind anomalies were westerly over the eastern half of the equatorial Pacific. Upper-level (200-hPa) wind anomalies were easterly along the equatorial Pacific. An anomalous anticyclonic couplet straddles the equator around the east-central Pacific.

The Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO) appears active, however, given the strength and persistence of the El Niño event, El Niño remains the dominant influence on the forecast.

Outside of the Equatorial Pacific, SST anomalies are broadly positive in the North Pacific and Atlantic basins. Positive SST anomalies are also present around the western and southern Alaskan coastlines, though much weaker than in prior months. SST anomalies are also positive along the west coast of the U.S., in the Gulf of Mexico, and up much of the East Coast. Negative and neutral to weakly positive SST anomalies are present off the coast of New England and the northern mid-Atlantic states.

Some modeling systems are indicating the potential for a sudden stratospheric warming during mid to late January. Uncertainty is high for such events as they are relatively rare, and forecasting impacts at the surface adds another layer of uncertainty. Should stratospheric warming occur, intraseasonal variability over some parts of the central and eastern CONUS could be increased.

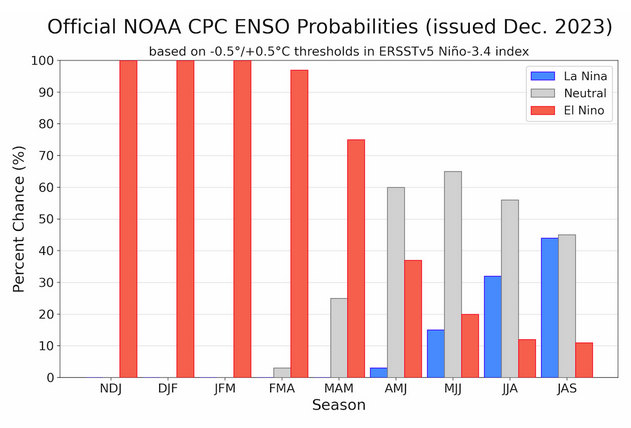

PROGNOSTIC DISCUSSION OF SST FORECASTS

The CPC Niño3.4 SST consolidation forecast shows a steady signal for Nino3.4 standardized anomaly values above 1.0 deg C through MAM, then a drop to near average values for the remainder of the outlook period. Data from the NMME suite of models have a similar pattern, though many of those models have individual members indicating some values less than -0.5 deg C by late in the Northern Hemisphere summer of 2024. The official NOAA CPC ENSO probabilities indicate that El Nino is favored through MAM, with ENSO-Neutral through JJA, and about equal probabilities for ENSO-Neutral and La Nina in JAS 2024.

30-DAY OUTLOOK DISCUSSION FOR JANUARY 2024

The January 2024 temperature and precipitation outlooks are based on: the Weeks 3-4 model guidance (valid for early to mid-January), the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME), and International Multi-Model Ensemble (IMME) for January, consolidation (statistical and dynamical tools), El Niño composites, consideration of the forecasted state of the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO), and decadal trends . Above-average sea surface temperatures continue across the central and eastern equatorial Pacific, while enhanced convection was observed at the Date Line with suppressed convection around Indonesia during the past month. The oceanic and atmospheric observations reflect El Niño conditions which are likely to persist through the winter.

El Niño remains the major climate driver and is expected to be the primary influence on the mid-latitude circulation pattern and associated January temperature and precipitation. Since late November, the MJO has propagated eastward from the Indian Ocean to the Pacific. As of mid-December, the enhanced (suppressed) phase of the MJO is centered over the Western (Eastern) Hemisphere. Lagged composites, based on phase 8 of the Real-time Multivariate MJO index, were considered for the January temperature outlook. However, enhanced convection across the western Indian Ocean, associated with the positive Indian Ocean Dipole (+IOD), along with El Niño may continue to disrupt any typical MJO response. Once the +IOD diminishes, the MJO could provide more influence on the mid-latitude circulation pattern over North America. The potential for a sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) is being monitored as zonal winds at 10-hPa over the Arctic are weaker than normal and many ensemble members from the GEFSv12 have a continued weakening. If a SSW were to occur, that could lead to high-latitude blocking, a negative Arctic Oscillation, and an increased chance of a colder outcome for parts of the contiguous U.S. (CONUS). A SSW event is uncertain but it will be monitored for the updated January outlook released on December 31.

Temperature

Month-to-date (December 1 to 19) temperatures have averaged above-normal throughout the CONUS with the largest anomalies (more than +7 degrees F) observed across the northern Great Plains and Upper Mississippi Valley. Following a positive Arctic Oscillation (AO) during mid-December, many of the GEFS ensemble members depict a more neutral or negative AO by the beginning of January. This change in the AO could promote at least more near normal temperatures for parts of the lower 48 States during January. Given the ongoing El Niño with enhanced Pacific flow over North America, overall mild temperatures are likely to continue from December 2023 into January 2024. The calibrated GEFS and ECMWF models for weeks 3-4 (valid January 3-16) feature increased above-normal temperature probabilities across most of the western and northern CONUS with a cold signal limited to the Southeast. Despite this cold signal during early to mid-January, equal chances (EC) of below, near, or above-normal temperatures are forecast for the Southeast since no other monthly tool supports increased below-normal temperature probabilities. The most likely areas to experience above-normal temperatures for the month include the Pacific Northwest, Great Basin, Northern Rockies, much of California, and the northern tier of the CONUS. This coverage is consistent with dynamical model guidance and El Niño composites. Sparse snow cover is expected to persist across Minnesota, the Dakotas, and eastern Montana heading into January which leads to enhanced above-normal temperature probabilities. The NMME, consolidation tool, and El Niño composites favor above-normal temperatures throughout Alaska with slightly lower probabilities forecast for southwestern Alaska.

Precipitation

The January precipitation outlook reflects El Niño composites and the likelihood of an active southern storm track with above-normal precipitation most likely for much of the West Coast along with much of the Gulf Coast and Southeast. EC is forecast for Washington since input models to the NMME vary on the precipitation signal. The highest forecast confidence in the precipitation outlook exists across south Georgia and Florida where probabilities exceed 50 percent for above-normal precipitation. The week 3-4 GEFS and ECMWF models, NMME, IMME, and El Niño composites all strongly support above-normal precipitation across that area of the Southeast. El Niño composites, the consolidation tool, and the IMME support increased below-normal precipitation probabilities from the Great Lakes southward to the Ohio Valley. For the remainder of the CONUS, weak or conflicting signals among the tools result in a forecast of EC. Based on the consolidation tool and week 3-4 model guidance, above-normal precipitation is slightly favored for parts of southeastern Alaska.

SUMMARY OF THE OUTLOOK FOR NON-TECHNICAL USERS (Focus on January through March)

El Niño conditions are currently observed, and equatorial sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are above average across the central and eastern Pacific Ocean. The El Niño Advisory remains in effect, and tropical Pacific atmospheric anomalies are consistent with El Niño. El Niño is expected to continue through the Northern Hemisphere winter, with a transition to ENSO-neutral favored during April-June 2024.

Temperature

Jan-Feb-Mar (JFM) 2024 Temperature Outlook favors above-normal temperatures for Alaska, the west coast of the Contiguous United States (CONUS), and from the Northern Rockies across the Great Lakes to the mid-Atlantic and Northeast. The highest odds for above-normal temperatures are across the Northwest, northern New England, and much of Alaska. Near normal temperatures are favored for parts of the Central and Southern Plains and parts of the Southeast. The overall pattern favoring above-normal temperatures across the northern CONUS with near-normal or below-normal temperatures favored for the southern tier of the CONUS persists through Mar-Apr-May (MAM) 2024.

Precipitation

The JFM 2024 Precipitation Outlook depicts elevated probabilities for below-normal precipitation over southwestern Alaska and elevated chances of above-normal precipitation over northern and southeast mainland Alaska. Below-normal precipitation is favored from the Northern Rockies to the Great Lakes and into the Ohio Valley. Above-normal precipitation is favored over much of the West Coast, with a slight tilt toward above-normal over parts of the central CONUS. The highest confidence for above-normal precipitation is over the Southeast CONUS where teleconnections from El Niño are strongest.

For both temperature and precipitation, areas depicted in white and labeled “EC” (Equal-Chances) are regions where climate signals are weak or inconsistent, and thus equal odds for either above-, near- or below-normal seasonal mean temperatures and seasonal total precipitation amounts are favored.

BASIS AND SUMMARY OF THE CURRENT LONG-LEAD OUTLOOKS

PROGNOSTIC TOOLS USED FOR U.S. TEMPERATURE AND PRECIPITATION OUTLOOKS

Dynamical model forecasts from the Copernicus (C3S) and NMME multi-model ensemble systems are used for the first three and six leads respectively, as well as individual model forecasts from the Climate Forecast System version 2 (CFSv2) and European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) models as available. The objective, historical skill weighted consolidation that combines both dynamical and statistical forecast tools was also considered throughout all leads.

El Niño impacts were considered given the strength and forecast persistence of the El Niño event through the MAM 2024 season, and El Niño composites and correlation/regression of temperature and precipitation with the Niño3.4 region were used to determine typical El Niño impacts. Statistical guidance such as the global SST based Constructed Analog (CA) and long term temperature and precipitation trends played a role in many of the outlook seasons, particularly beyond lead 6 when dynamical model guidance is unavailable. Coastal SST and sea ice anomalies are considered at early leads. Snow cover was also considered for the Northern Plains.

PROGNOSTIC DISCUSSION OF OUTLOOKS – JFM 2024 TO JFM 2025

TEMPERATURE

The JFM 2024 Temperature Outlook favors above-normal temperatures for Alaska, the west coast of the Contiguous United States (CONUS), and from the Northern Rockies across the Great Lakes to the mid-Atlantic and Northeast. The highest odds for above-normal temperatures are across the Northwest, northern New England, and much of Alaska. Near-normal temperatures are favored for parts of the Central and Southern Plains and parts of the Southeast. The overall pattern favoring above-normal temperatures across the northern CONUS with near-normal or below-normal temperatures favored being restricted to the southern tier of the CONUS persists through Mar-Apr-May (MAM) 2024. The trend signals are weak during JFM for much of the CONUS and Alaska, so the forecast is largely based on patterns associated with El Nino and dynamical model guidance. Some of the guidance is indicating a warmer signal across portions of the Southeast, so some of the areas where near-normal temperatures were indicated last month for JFM are removed. Odds for above-normal temperatures were lowered across the Ohio Valley and Lower Great Lakes due to additional uncertainty associated with the potential for an SSW and to reflect recent model guidance. Near-normal temperatures are favored for the Central and Southern Plains and parts of Southeast during JFM 2024, supported by a consolidation of dynamical and statistical models. These areas of favored near-normal temperatures represent regions where there is interplay in the tools between expected impacts from El Niño, decadal trends , and dynamical model guidance, leading to a forecast of enhanced near-normal probabilities. El Niño composites tilt weakly toward below normal in the Southeast during winter months, which is balanced by above normal trends and a less confident but still above normal tilt in dynamical model forecasts, which overall supports near normal temperatures.

The tilt toward above normal temperatures is maintained over Alaska, the West Coast, and northern parts of the CONUS until March-April-May (MAM) 2024 when El Niño impacts are expected to begin to wane, and higher uncertainty (EC) is introduced in the Northern Plains. Though the season(s) may tilt above normal in the mean, some periods of cold may occur during winter and early spring due to intraseasonal variability.

During FMA through AMJ 2024, below-normal temperatures are favored over parts of the Central and Southern High Plains, reflecting the associated impacts of ENSO. That impact is seen in regressions of temperature and Nino3.4 as well as the SST-CA.

From spring (May-June-July, MJJ) into summer and the remaining forecast leads, El Niño impacts are expected to decrease and decadal trends become the primary driver of the forecasts. Predictability decreases in spring and more EC is depicted in the forecasts in the central CONUS. Above-normal temperatures are favored over much of the CONUS through summer 2024 and shift toward the east coast by winter 2024-2025. Over Alaska, above-normal temperatures are likely through MJJ 2024 given expected impacts from El Niño, and a mixture of EC and above-normal temperatures are forecast over the state for the remainder of the forecast leads, mainly driven by trends .

PRECIPITATION

The JFM 2024 Precipitation Outlook depicts enhanced probability of below-normal precipitation over southwestern Alaska and above-normal precipitation over northern and southeastern Mainland Alaska. The southwestern below-normal precipitation area is consistent with expected El Niño teleconnections, and the northern above-normal precipitation area is supported by El Niño and decadal trends. Below-normal precipitation is favored from the Northern Rockies to the Great Lakes, including parts of the Ohio Valley, where there is a stronger signal for below-normal precipitation compared to the prior outlook for JFM. Above-normal precipitation is favored over much of the West Coast, across the Great Basin, Central Rockies, and into the Central Great Plains to reflect likely impacts from El Niño and the potential for southerly shifted storm track. Given a strong connection to El Niño over the Southeast CONUS, the highest confidence for above-normal precipitation is over the Gulf States and along the East Coast to South Carolina (60 to 70 percent), with probabilities decreasing toward New England. Probabilities of at least 50 to 60 percent for above-normal precipitation, remains along parts of the Gulf coast through MAM 2024. El Niño impacts dominate forecast evolution through MAM 2024 for the precipitation outlook, and are modified based on other tools such as NMME, C3S, and decadal trends , as well as a consolidation of statistical and dynamical models.

El Niño impacts are less pronounced in the forecasts beginning in AMJ 2024, and dynamical model guidance (where available) and decadal trends become the primary considerations. A tilt toward above- normal precipitation is depicted over parts of the southeastern CONUS and shifting northward to the Ohio Valley to the Northeast in AMJ through ASO 2024, and re-emerges for parts of the eastern CONUS by winter 2024 as decadal trends tilt toward above-normal precipitation. Based mainly on decadal trends , below-normal precipitation is favored over parts of the Northwest and Northern Plains through fall 2024.

For Alaska, above-normal precipitation is favored over northern parts of the state through MAM 2024, owing to both El Niño impacts and precipitation trends . Below-normal precipitation is favored for the southwest coast in JFM 2024, mainly driven by expected El Niño impacts, before above-normal precipitation begins to dominate the forecasts by Spring 2024, supported by NMME and C3S. From SON 2024 onward, long term precipitation trends which favor above-normal precipitation across much of northern mainland Alaska dominate the forecast over Alaska.

The key piece of information used by NOAA follows.

| It looks like El Nino through the forecast period. It does start to begin to reduce the intensity in FMA2024. There is increasing confidence that this El Nino will weaken in the Spring into the summer which is shown here as the probabilities of El Nino begin to converge with the probabilities of ENSO Neutral and even La Nina at the very end of the forecast period. |

Resources

–

| I hope you found this article interesting and useful. |

–