On the third Thursday of the month right on schedule NOAA issued their updated Seasonal Outlook which I describe as their Four-Season Outlook because it extends a bit more than one year into the future. The information released also included the Mid-Month Outlook for the following month plus the weather and drought outlook for the next three months. I present the information issued by NOAA and try to add context to it. It is quite a challenge for NOAA to address the subsequent month, the subsequent three-month period as well as the twelve successive three-month periods for a year or a bit more.

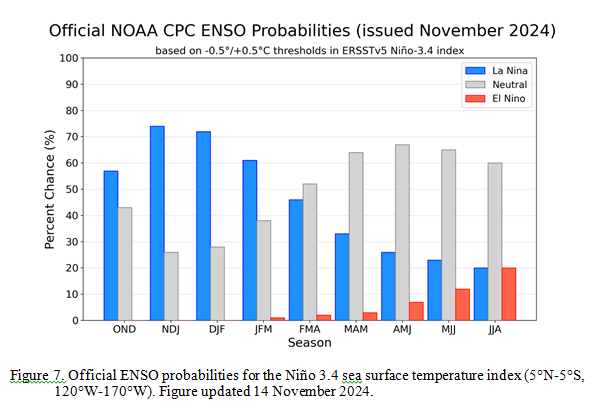

With respect to the long-term part of the Outlook which I call the Four-Season Outlook, the timing of the transition from Neutral to LaNina has been challenging to predict. We are still in ENSO Neutral. La Nina is the likely scenario soon, but the strength of the La Nina may be fairly weak.

From the NOAA discussion:

“Taken collectively, statistical and dynamical model forecast guidance of the Niño3.4 index favor the development of a weak and most likely short duration La Niña event. Some statistical model forecasts do favor a continuation of ENSO-neutral into and through winter 2024-2025. Dynamical model guidance predictions tend to support weak La Niña conditions to develop, including the majority of participant models from the NMME and C3S forecast suites. Most recent observations and the forecast guidance noted above favor La Niña to emerge during OND 2024 (57% chance) and it is expected to persist through JFM 2025. After JFM 2025, ENSO-neutral is the most likely category into the northern hemisphere summer of 2025.”

“Based on a weak La Nina and models overdoing trends, observed trends become more of the signal. Furthermore, higher frequency patterns (AO, MJO, and stratospheric variability) that result in increased uncertainty can also play a larger role. Those modes are largely not predictable on seasonal timescales,”

I personally would not have total confidence in this outlook given the uncertainty about there actually being a La Nina and its strength if it does happen. I forecasted the JAMSTEC three-season forecast last Saturday LINK. I do not have a lot of confidence that NOAA knows how to deal with a La Nina Modoki. The number of El Nino and La Nina events since 1950 is a fairly small number. When you further segment them by strength you end up with a very small number of events in each category (El Nino v La Nina and three or four categories of strength within each of perhaps 8 to 10 subcategories. This makes both statistical methods and dynamical models have a large error range. We are pretty confident now that we will have either a weak La Nina or Neutral with a La Nina bias meaning it will be in the Neutral Range but closer to a La Nina than an El Nino. This suggests that there is value in this forecast. The maps show the level of confidence that NOAA (really the NOAA Climate Prediction Center) has for the outlook shown when they show a part of the U.S. or Alaska differing from normal.

It will be updated on the last day of November.

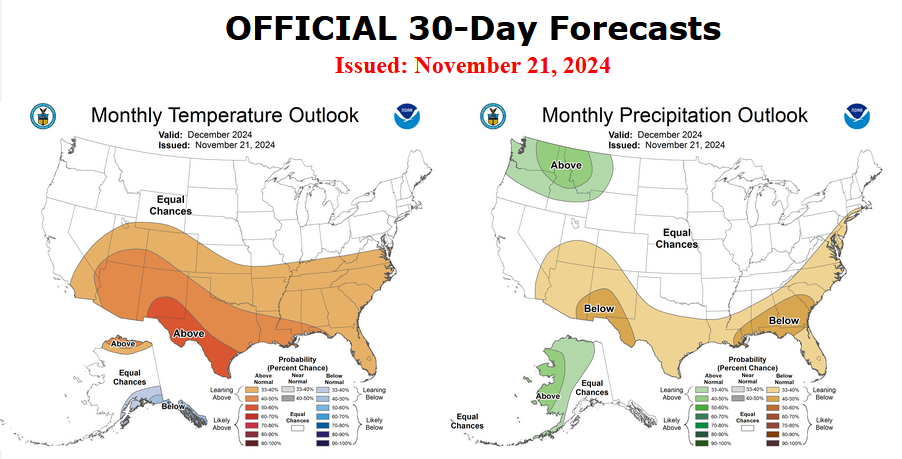

Then we look at a graphic that shows both the next month and the next three months.

The top row is what is now called the Mid-Month Outlook for next month which will be updated at the end of this month. There is a temperature map and a precipitation map. The second row is a three-month outlook that includes next month. I think the outlook maps are self-explanatory. What is important to remember is that they show deviations from the current definition of normal which is the period 1991 through 2020. So this is not a forecast of the absolute value of temperature or precipitation but the change from what is defined as normal or to use the technical term “climatology”.

| Notice that the Outlook for next month and the three-month Outlook are fairly similar except in two places. This tells us that January and February will be substantially the same as December for most of CONUS and Alaska. Part of the explanation for this is that NOAA expects La Nina to impact all three months. |

–

The full NOAA Seasonal Outlook extends through December/January/February of 2026 (yes that is more than a year out). All of these maps are in the body of the article. Large maps are provided for December and the three-month period December/January/February Small maps are provided beyond that through December/January/February of 2026 with a link to get larger versions of these maps. NOAA provides a discussion to support the maps. It is included in the body of this article.

In some cases, one will need to click on “read more” to read the full article. For those on my email list where I have sent the url of the article, that will not be necessary.

The maps are pretty clear in terms of the outlook.

And here are large versions of the three-month DJF 2025 Outlooks

First temperature followed by precipitation.

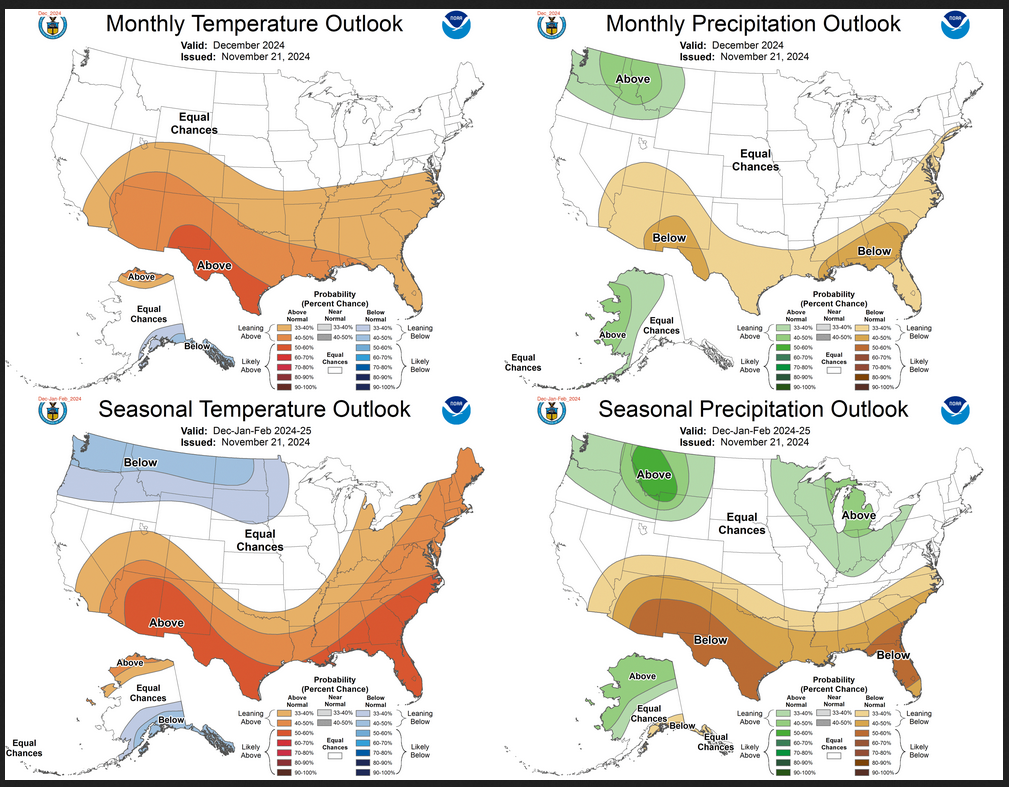

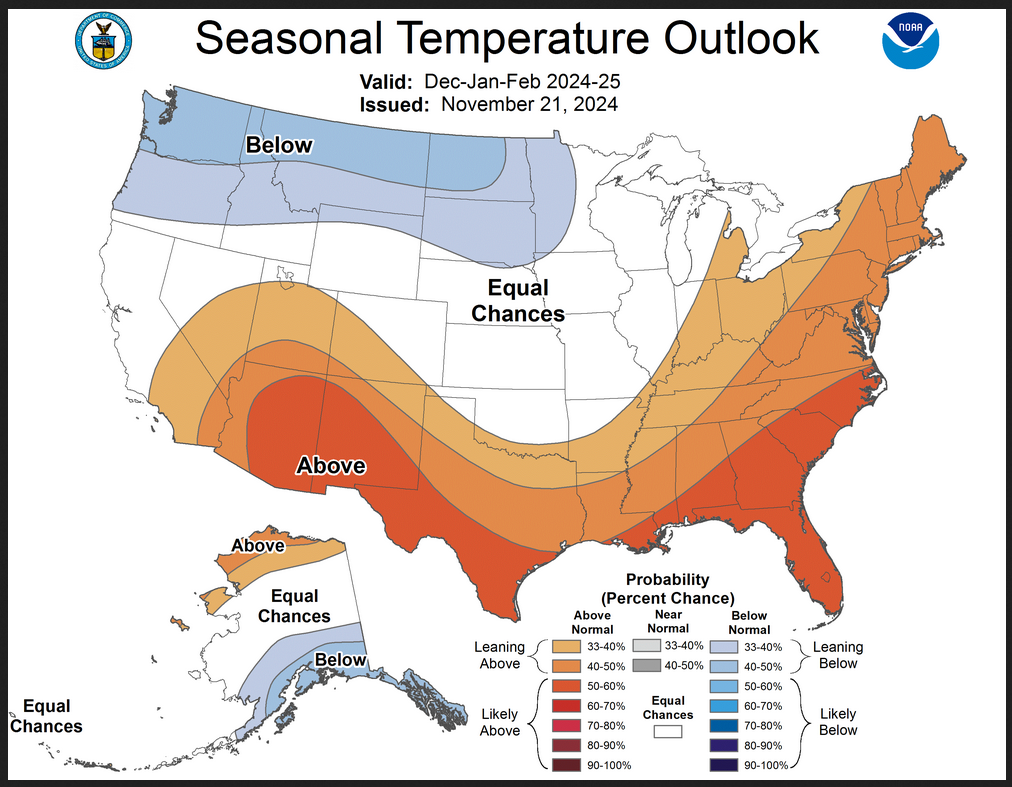

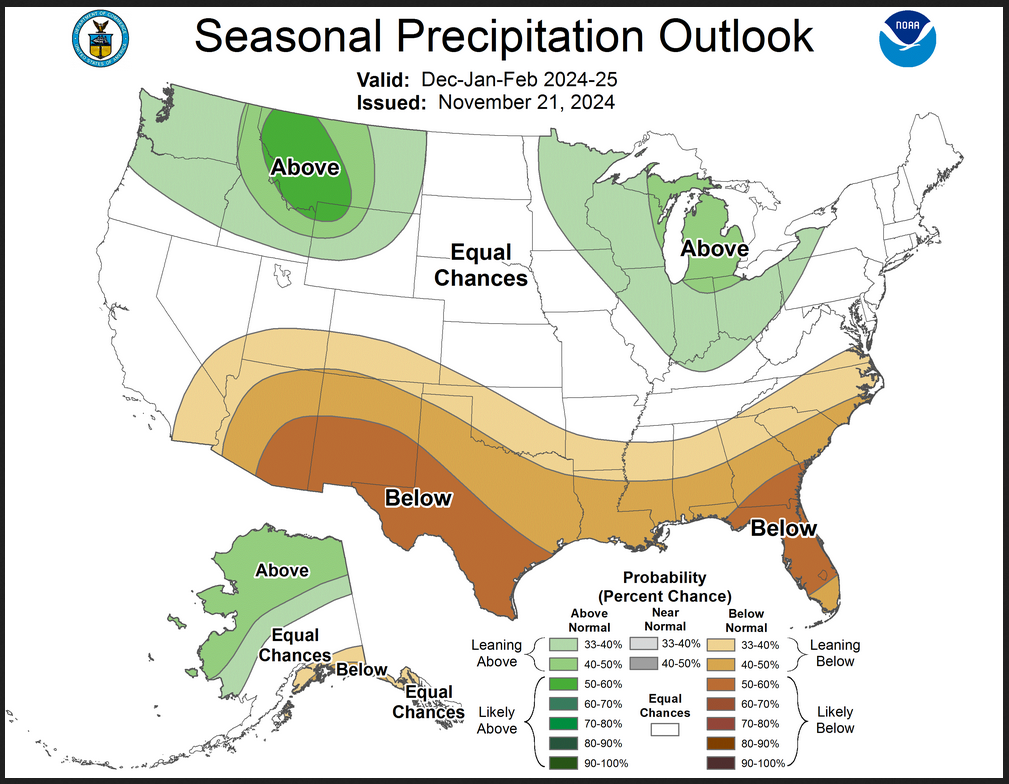

| These maps are larger versions of what was shown earlier. This is a pretty definitive pattern. |

NOAA Discussion

Maps tell a story but to really understand what is going you need to read the discussion. I combine the 30-day discussion with the long-term discussion and rearrange it a bit and add a few additional titles (where they are not all caps the titles are my additions). Readers may also wish to take a look at the article we published last week on the NOAA ENSO forecast. That can be accessed HERE.

I will use bold type to highlight some especially important things. All section headings are in bold type; my comments, if any, are enclosed in brackets [ ].

CURRENT ATMOSPHERIC AND OCEANIC CONDITIONS

ENSO-neutral continued through early November 2024, with near- to below-average SSTs from about 170W to 100W along the equator and off equatorial SSTs just above normal. The equatorial central Pacific SSTs, exhibited a mix of cooling and warming during the last 4 weeks, with some portions of the Nino3.4 region, so no strong movement toward La Nina was noted. The latest weekly Niño indices ranged from +0.2°C (Niño-4) to -0.3°C (Niño-3.4), similar to values from October. When removing the global tropical mean to construct a Nino3.4 value relative to the global tropics, the relative value is -0.76°C, so that may be why we are seeing some signals consistent with La Nina but not robustly clear indications, yet. [Author’s Note: This was discussed in our article last week which referred to an article by Emily Becker so that is the best way to understand this. HERE is the link to the Emily Becker ENSO Blog Post.]

Equatorial ocean heat content for the area from 180 to 100W remained below normal, near -0.5°C. Below-average temperatures remain at depth in the east-central and eastern Pacific Ocean, while above-average temperatures prevail at depth and near the surface in the western Pacific. Above-average OLR (suppressed convection and precipitation) was observed around the Date Line. Below-average OLR (enhanced convection and precipitation) was evident over the Philippines. Low-level (850-hPa) wind anomalies were mostly near average across the equatorial Pacific Ocean, with a small region of westerly wind anomalies over the eastern Pacific Ocean. Upper-level (200-hPa) wind anomalies were mostly near average across the equatorial Pacific Ocean

Then MJO was active during October and moved across the central Pacific in late October. The MJO is forecast to remain active for at least the rest of November, potentially enhancing low-level easterly anomalies across the central and eastern Pacific basins.

SSTs remain warmer than normal for most areas of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, as well as the mid-latitude regions of the Pacific. Below-normal ocean surface temperatures are evident in parts of the Gulf of Alaska and the Bering Sea, as well as the Chukchi Sea where there are some pockets of new ice at less than 4-tenths coverage. Sea ice is largely in place for much of the Chukchi and Beaufort seas (https://tgftp.nws.noaa.gov/data/raw/fz/fzak80.pafc.ice.afc.txt), so any signal from a late onset of sea ice is not applicable during DJF. Drought conditions that rapidly expanded across much of the CONUS during late summer and early autumn have been ameliorated across much of the central Great Plains while continuing to intensify across much of the Southeast, Central Appalachians, and the Northeast.

PROGNOSTIC DISCUSSION OF SST FORECASTS

Taken collectively, statistical and dynamical model forecast guidance of the Niño3.4 index favor the development of a weak and most likely short duration La Niña event. Some statistical model forecasts do favor a continuation of ENSO-neutral into and through winter 2024-2025. Dynamical model guidance predictions tend to support weak La Niña conditions to develop, including the majority of participant models from the NMME and C3S forecast suites. Most recent observations and the forecast guidance noted above favor La Niña to emerge during OND 2024 (57% chance) and it is expected to persist through JFM 2025. After JFM 2025, ENSO-neutral is the most likely category into the northern hemisphere summer of 2025.

30-DAY OUTLOOK DISCUSSION FOR DECEMBER 2024

The December 2024 Temperature and Precipitation Outlooks are based on: the Weeks 3-4 model guidance, the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME), and International Multi-Model Ensemble (IMME), the consolidation (combination of statistical and dynamical tools), consideration of potential Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO) influences, and decadal trends . Although El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO)-neutral conditions continue, below-average sea surface temperature anomalies are observed across the east-central Pacific. La Niña is favored to develop by the end of December and La Niña composites were a factor, especially in the precipitation outlook.

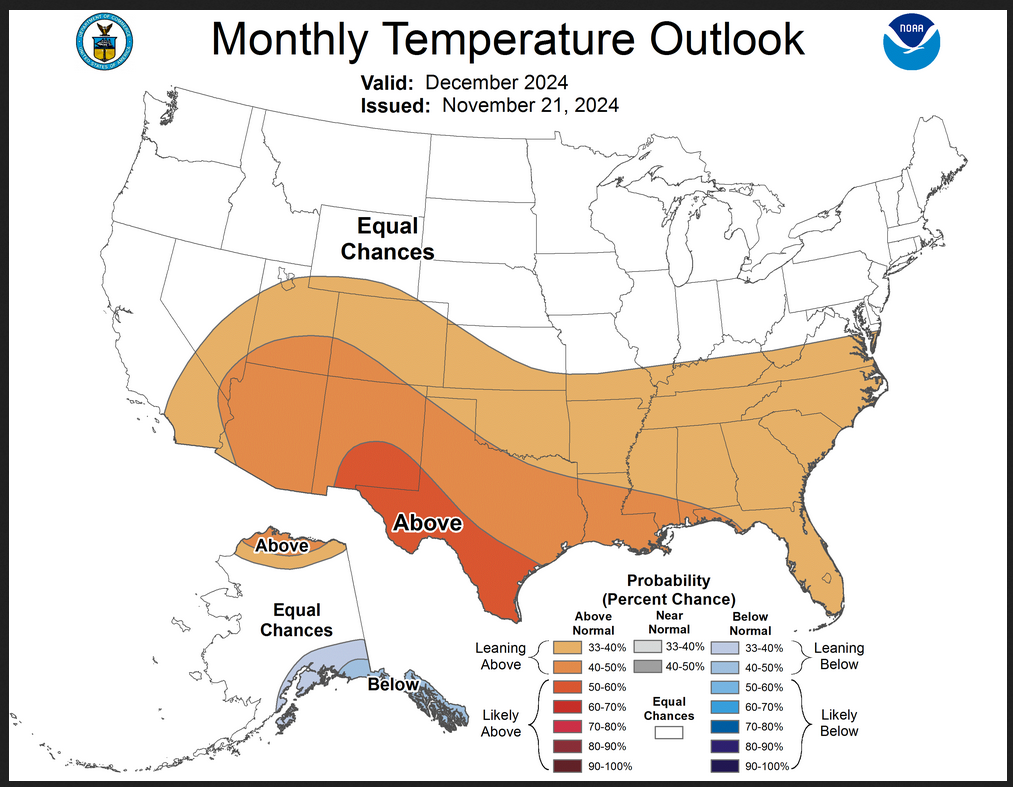

Temperature

During late November, a major pattern change is forecast as an amplified 500-hPa ridge over Alaska results in surface high pressure with anomalous cold shifting south from Canada into the central and eastern contiguous U.S. (CONUS). By the beginning of December, the GEFS and ECMWF ensemble means are in good agreement and consistent that below-normal temperatures extend from the Great Plains to the East Coast. The latest week 3-4 GEFS (valid December 5-18) favors below-normal temperatures continuing across the Great Lakes and Northeast. Lagged MJO composites would favor a flip to above-normal temperatures across the central and eastern CONUS by mid-December. Due to an expected variable temperature pattern during December, equal chances (EC) of below, near, or above-normal temperatures are forecast across the Northern Great Plains, Midwest, and Northeast. The week 3-4 models, NMME, consolidation, and decadal trends support increased above-normal temperature probabilities across the Southeast, Lower Mississippi Valley, Southern Great Plains, and Southwest. The largest above-normal temperature probabilities (more than 50 percent) are forecast for the Rio Grande Valley and southern New Mexico where the strongest warm signal exists in the consolidation tool. EC is forecast for the Pacific Northwest, Northern Rockies, and much of California due to a weak signal in the NMME.

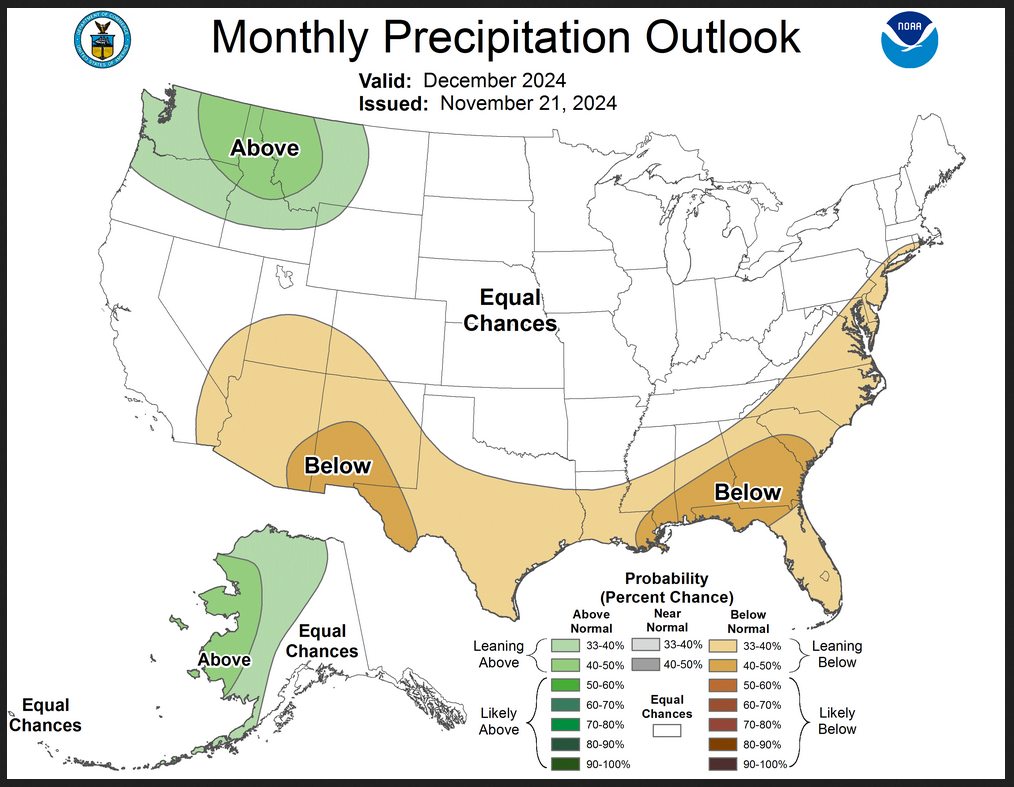

Precipitation

The NMME, consolidation, and any influence from La Niña favor below-normal precipitation across the Southeast [Author’s Note: They may mean Southwest], Gulf Coast States, and Southeast. This favored dryness extends northward along the East Coast to the Mid-Atlantic and southern New England based on the NMME and daily CFS model runs. However, there is only a slight lean towards below-normal precipitation for portions of the eastern CONUS since an amplified 500-hPa trough over eastern North America early in the month would favor multiple low pressure systems tracking either along or offshore of the East Coast. Below-normal precipitation probabilities are also lower across the Florida Peninsula as an eastward propagating MJO over the Western Hemisphere could eventually lead to a more active southern stream with enhanced precipitation. In addition, the daily CFS model runs have less support for below-normal precipitation for that part of the Southeast. Week 3-4 model output, most inputs to the NMME, and La Niña composites support elevated above-normal precipitation probabilities for the Pacific Northwest and Northern Rockies. A large spatial extent of EC is forecast for the remainder of the CONUS due to a weak model signal and limited skill at this time lead for a monthly precipitation outlook.

The increased chances of above (below)-normal temperatures forecast for the North Slope (southeastern Alaska) are supported by the NMME and consolidation tool. Lagged MJO composites would also favor below-normal temperatures across southeastern Alaska during mid-December. The favored wetness across western and northern Mainland Alaska is based on the NMME and also consistent with decadal trends.

SUMMARY OF THE OUTLOOK FOR NON-TECHNICAL USERS (focus on December-January-February 2024-2025)

El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO)-neutral conditions remain present, as equatorial sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are near-to-below average in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean. A La Niña Watch remains in effect, with La Niña most likely to emerge in October-December 2024 (57% chance) and is expected to persist through January-March 2025. Any La Niña event that develops this autumn is favored, however, to be a weak short duration event.

Temperature

The December-January-February (DJF) 2024-2025 temperature outlook favors above-normal seasonal mean temperatures from the Southwest across the Southern Plains to the Southeast, then northward from the Great Lakes to New England. Below-normal seasonal mean temperatures are favored from the Pacific Northwest to the Northern Great Plains.

Precipitation

The DJF 2024-2025 precipitation outlook depicts enhanced probabilities of below-normal seasonal total precipitation amounts along most of the southern tier of the contiguous U.S. (CONUS) and for parts of southeast Mainland Alaska and Alaska Panhandle. The greatest odds of below-normal precipitation (greater than 50 percent) are forecast for parts of the Southwest and Southern Plains. Above-normal precipitation is favored for parts of the Pacific Northwest, northern Rockies, central Great Lakes, and western and northern Alaska. The strongest of those signals is over the northern Rockies.

Equal chances (EC) are forecast for areas where probabilities for each category of seasonal mean temperatures and seasonal total precipitation amounts are expected to be similar to climatological probabilities.

BASIS AND SUMMARY OF THE CURRENT LONG-LEAD OUTLOOKS

PROGNOSTIC TOOLS USED FOR U.S. TEMPERATURE AND PRECIPITATION OUTLOOKS

The development of potential La Niña conditions in the atmosphere-ocean system in the Pacific contributed to the outlooks from DJF 2024-2025 through FMA 2025. Although typical La Niña impacts are less likely to occur during a weak event (currently favored), La Niña still tilts the odds in the outlook forecast probabilities. Coastal SSTs and constructed analogue forecasts keyed to current SSTs are utilized in preparation of the outlooks. Soil moisture is not largely considered for the outlook during this time of year as correlations with soil moisture are quite low for initial conditions during the cool season. Dynamical model guidance from the NMME and C3S prediction suites (first 5 and 3 leads respectively), statistical forecast tools, long-term temperature and precipitation trends , and an objective, historical skill weighted combination of much of the above guidance strongly contributed to the final outlooks.

PROGNOSTIC DISCUSSION OF OUTLOOKS – DJF 2024 TO DJF 2025

TEMPERATURE

The December-January-February (DJF) 2024-2025 temperature outlook favors above-normal seasonal mean temperatures from the Southwest across the Southern Plains to the Southeast, then northward from the Great Lakes to New England. Below-normal seasonal mean temperatures are favored from the Pacific Northwest to the Northern Great Plains. The DJF outlook has slightly lower odds for below-normal temperatures across North Dakota and Minnesota than the DJF outlook released in October due to the continued delay in La Nina and slightly increased odds for a weak event. Additionally, the NMME suite was judged to be too warm over the Northern Great Plains despite a shift toward cooler outcomes in the model suite, many of the models were still showing above-normal temperatures. Based on a weak La Nina and models overdoing trends, observed trends become more of the signal. Furthermore, higher frequency patterns (AO, MJO, and stratospheric variability) that result in increased uncertainty can also play a larger role. Those modes are largely not predictable on seasonal timescales, though La Nina events and the westerly phase of the QBO [Author’s Note: See LINK] can result in less polar vortex splits or shifts.

Similar patterns (above-average temperatures favored largely across the southern tier and below-normal temperatures across the northern tier) are present in the outlooks through Feb-Mar-Apr 2025, with below-normal temperatures favored from the Northwest to the Northern Great Plains. A band of equal chances from central California to Wyoming, and across much of the Great Plains where higher frequency modes can often have their largest impacts.

Across Alaska, the DJF outlook for temperature favors above-normal temperatures across northern Mainland Alaska while favoring below-normal temperatures across southern Mainland Alaska and the Alaska Panhandle. The northern signal is related to trends and outlooks from the NMME and C3S, while the southern signal is more from La Nina, statistical tools, and the NMME model suite. Those two areas remain in the outlooks, with some minor modifications, through Mar-Apr-May, where the signal for below-normal temperatures recedes as trends become the dominant predictor.

During late Northern Hemisphere spring and early summer of 2025, trends become the dominant climate forcing. Areas in the Great Plains have the lowest odds being the areas with the weakest trends and higher variance. Coming out of a La Nina winter, dry signals across the southern tier can reinforce some of the trends in temperatures, especially across the western CONUS, so the odds of above-normal temperatures are relatively the highest in the Rockies and Southwest through the summer and autumn.

PRECIPITATION

The DJF 2024-2025 precipitation outlook favors above-normal seasonal total precipitation amounts for portions of the Pacific Northwest, northern Rockies, Michigan, and northern and western Alaska. Drier-than-normal conditions are most likely for the southern tier of the U.S. with the highest odds forecast for the Southwest and Southern Plains. For Southeast Mainland Alaska and the northern Alaska Panhandle, a slight tilt toward drier than normal conditions is forecast through MAM 2025.

As noted above, the favored development of La Niña conditions approaching the winter and consistent dynamical model forecast guidance is the basis for the outlook. The odds for above-normal precipitation are increased during DJF 2024-2025 relative to the outlook for DJF from October 2024 as the tools are showing more certainty. The most uncertain area in the precipitation outlook for DJF 2024-2025 is across the northern Great Plains, as signals are weak and mixed (NMME favors above-normal precipitation, where as calibrated versions remove the signal, and trends vacillate season to season). Moving through the FMA 2025 season, the enhanced likelihood of above-normal precipitation in the Great Lakes and Ohio Valley regions expands in coverage and probabilities increase maximizing in the southern Great Lakes and northern Ohio Valley area in JFM 2025. Positive precipitation trends also contribute strongly to these outlooks for some areas in the Midwest and Great Lakes. The precipitation outlook is highly uncertain east of the Appalachians in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast, as the storm track during La Nina years is typically more inland, but a weak La Nina will likely let other, shorter-lived climate forcings play larger roles in the overall storm track.

Favored below-normal precipitation across the south through FMA 2025 remains generally consistent with the forecast coverage and odds greatest for JFM 2025. The majority of the dynamical model guidance from the NMME and C3S model suites highlight substantially elevated odds for below-normal precipitation for the Far West (i.e., California/Nevada) for the winter seasons through FMA 2025. Given the anticipated generally weak ENSO forcing, this seems overdone, especially since some of the dynamical model guidance can sometimes overemphasize ENSO impacts during weaker events.

Given the lack of a clear, reliable ENSO signal after this winter/early spring, longer lead outlooks are primarily based on long term precipitation trends and depict low forecast coverage. The longer lead precipitation outlooks during the warm season generally have low forecast skill.

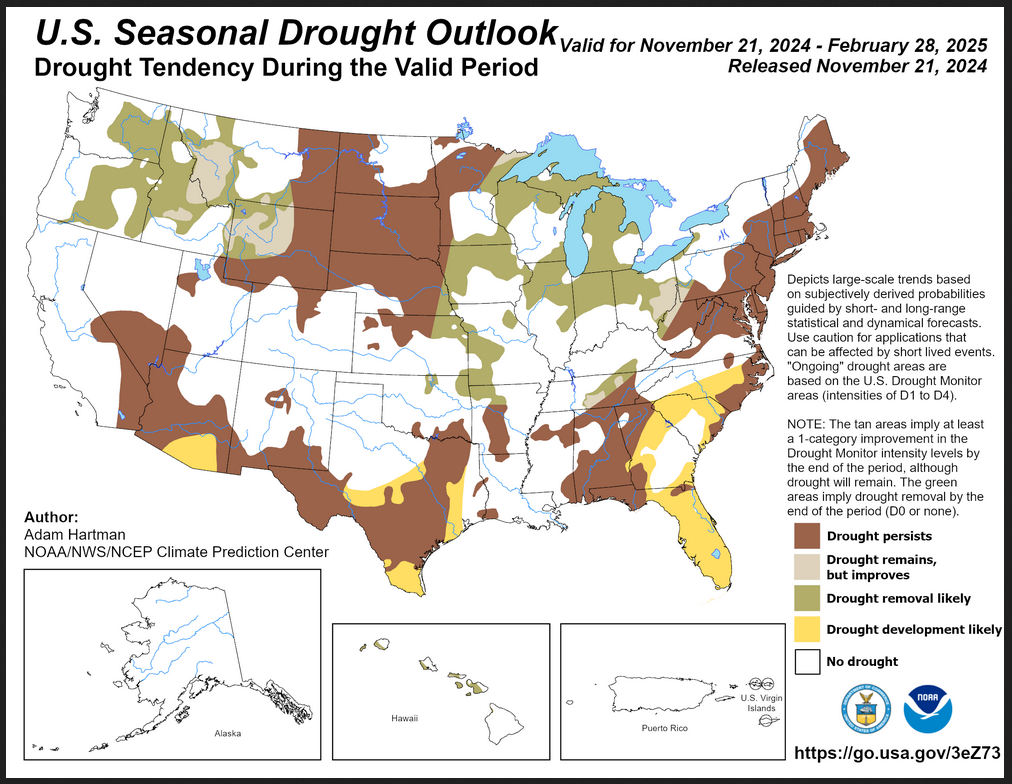

Drought Outlook

| The yellow is the bad news and there is a lot of it. And there is a large area where drought is expected to persist. The area where drought is expected to improve is also large. With a La Nina winter ahead, Drought is likely to expand in parts of the Southern Tier of states. Overall the level of drought is expected to remain the same or decrease slightly. |

Short CPC Drought Discussion

Latest Seasonal Assessment – Since the November-December-January Seasonal Drought Outlook (SDO) released in mid-October, marked improvements to drought conditions have occurred across central portions of the contiguous U.S. (CONUS) and parts of the Pacific Northwest, particularly since the start of November. This has been welcomed relief for many, given October was one of the driest on record for much of the CONUS. Unfortunately, drought conditions continued to expand in coverage or worsen across large areas of the Southwest, Northern Plains, Texas, and the eastern CONUS.

Looking forward to the December-January-February (DJF) SDO, La Niña conditions (cooler than average sea surface temperatures in the central to eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean) are forecast to develop through the first one to two months of the period. This typically favors a northward shifted mean storm track across North America leading to cooler and wetter conditions on average across the northern tier of the CONUS and warmer and drier conditions across the southern tier. However, the event is likely to be weak, thereby allowing other shorter-term climate modes to potentially cause increased variability throughout the season that may offset the average pattern that is typical with La Niña.

Drought is forecast to improve across much of the Pacific Northwest and northern Rockies, associated with wet conditions leading up to the DJF season and the favored development of La Niña. Although the southwestern CONUS is entering into its winter rainy season, La Niña conditions are likely to offset this signal, leading to broad drought persistence and even some development in southern Arizona, where Climate Prediction Center (CPC) outlooks favor higher odds of above average temperatures and below normal precipitation. Drought persistence is favored for much of the Great Plains, with some development also favored across parts of Texas, given the antecedent conditions and DJF being a drier time of year. The DJF precipitation outlook favors above normal precipitation odds across much of Great Lakes, Upper Midwest, and the Ohio Valley. Conversely, drought persistence is favored across much of the Lower Mississippi Valley and Deep South, where heavy precipitation leading up to the start of December is likely to offset the longer-term warm and dry signals through at least the end of 2024. Drought persistence is also favored in the Mid-Atlantic and coastal Northeast, where antecedent conditions are very dry and precipitation signals are lacking, but the cooler time of year offers some potential for soil moisture recharge when these regions do get precipitation.

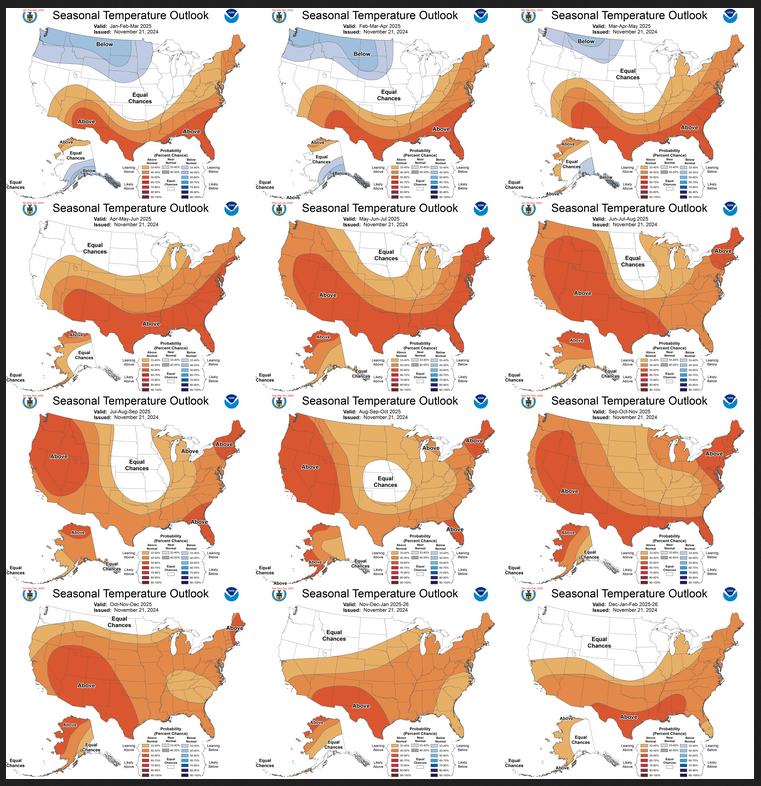

Looking out Four Seasons.

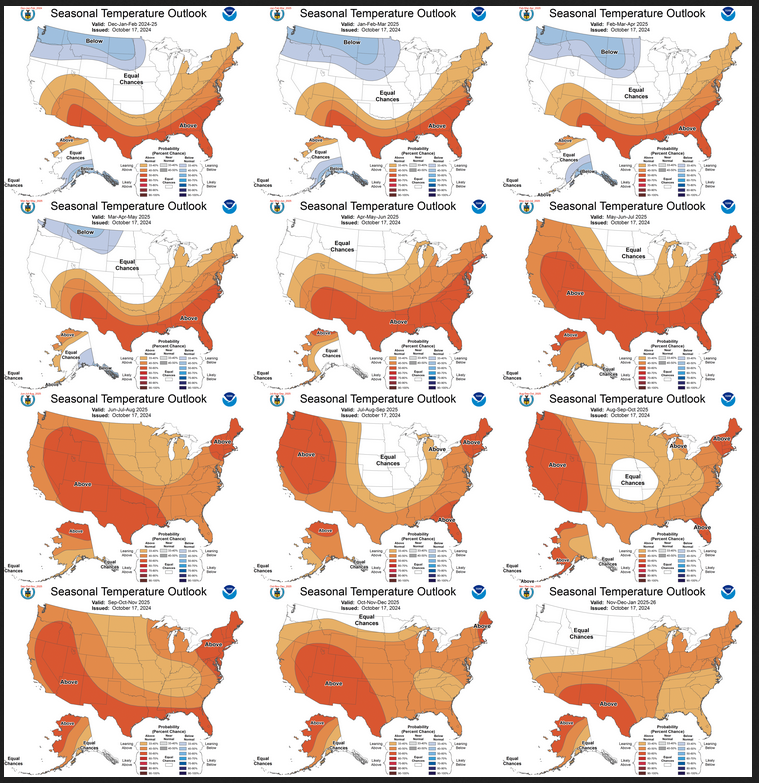

Twelve Temperature Maps. These are overlapping three-month maps (larger versions of these and other maps can be accessed HERE)

Notice that this presentation starts with Jan/Feb/March (JFM) since DJF is considered the near-term and is covered earlier in the presentation. The changes over time are generally discussed in the discussion but generally, you can see the changes easier in the maps. The discussion often provides the “why” and how the outlook might be different than what was issued last month.

Comparing the new outlook with the prior Outlook,

The easiest way to do the comparison is to print out both maps. If you have a color printer that is great but not needed. What I do is number the images from last month 1 – 12 starting with “1” and going left to right and then dropping down one row. Then for the new set of images, I number them 2 – 13. That is because one image from last month in the upper left is now discarded and a new image on the lower right is added. Once you get used to it, it is not difficult. In theory, the changes are discussed in the NOAA discussion but I usually find more changes. It is not necessarily important. I try to identify the changes but believe it would make this article overly long to enumerate them. The information is here for anyone who wishes to examine the changes. I comment below on some of the changes from the prior report by NOAA and important changes over time in the pattern.

| There has not been much of a change since last month. |

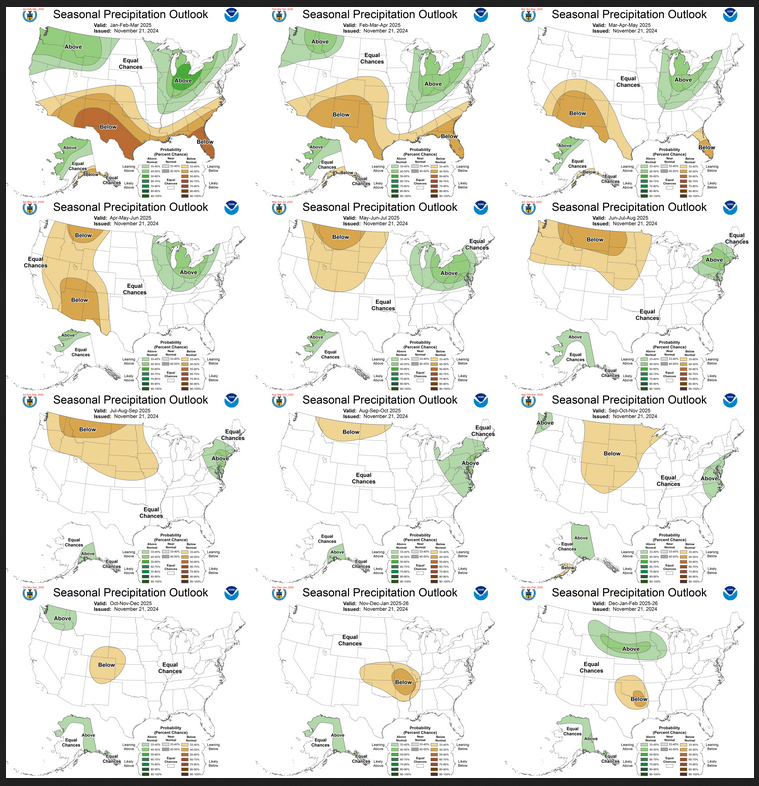

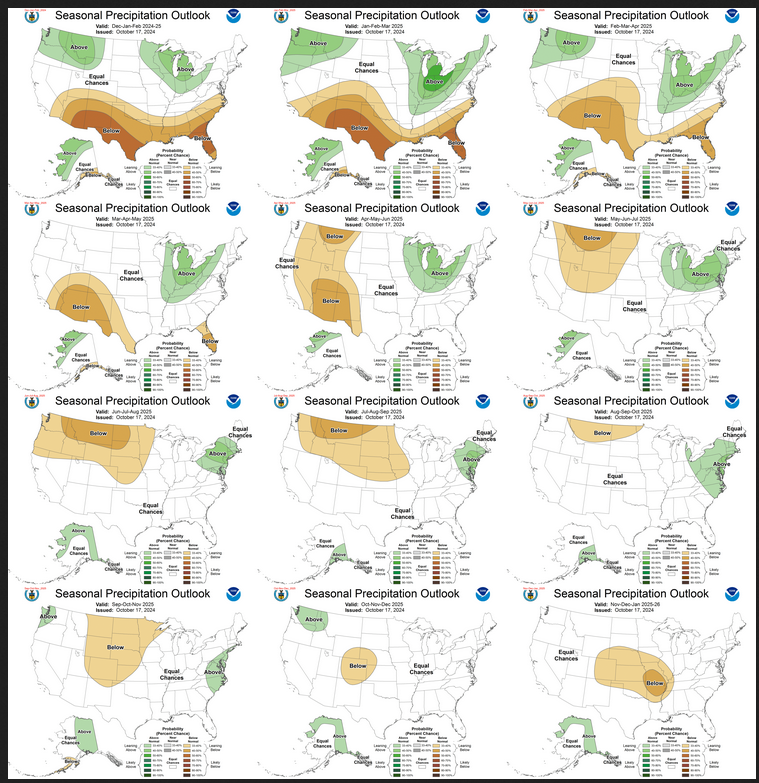

Similar to Temperature in terms of the organization of the twelve overlapping three-month outlooks.

Comparing the new outlook with the prior Outlook,

The maps that were released last month.

A good approach for doing this comparison is provided with the temperature discussion.

| The overall outlook is pretty much the same as last month. |

| It looks like ENSO is Neutral now however we should be in La Nina any day now. This type of graphic does not show how strong an El Nino or a La Nina is likely to be. What is forecast is a La Nina, which if it does occur, most likely will not be stronger than a marginal La Nina. |

Resources

Other Reports and Information

The Wildfire Report can be accessed HERE

–

| I hope you found this article interesting and useful. |

–