Preparing to Say Goodbye to La Nina Early in 2023. It seems as if it is taking forever but if the forecasters are correct, we are talking about four to six months from now.

Today is the third Thursday of the month so right on schedule NOAA has issued what I describe as their Four-Season Outlook. The information released also includes the Early Outlook for the single month of October plus the weather and drought outlook for the next three months. I present the information issued and try to add context to it. It is quite a challenge for NOAA to address the subsequent month, the subsequent three-month period as well as successive three-month periods for a year or a bit more.

It is very useful to read the excellent discussion that NOAA issues with this Seasonal Outlook. NOAA seems to be more confident about making predictions beyond six months. They even predicted a good monsoon next summer which they never do this far in advance.

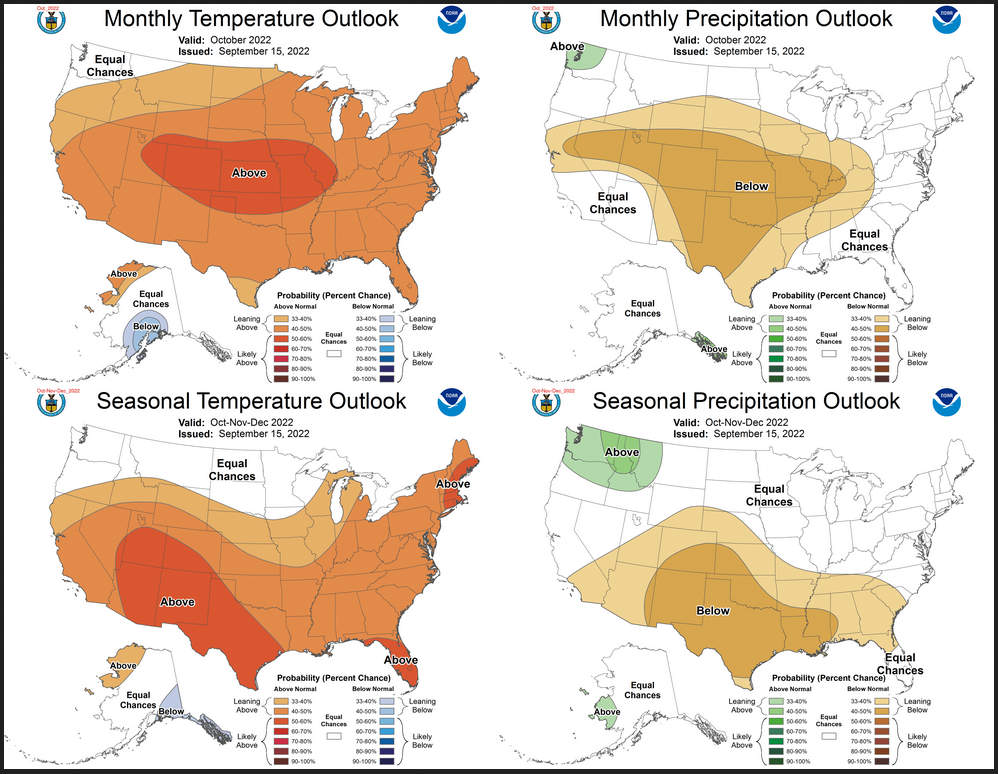

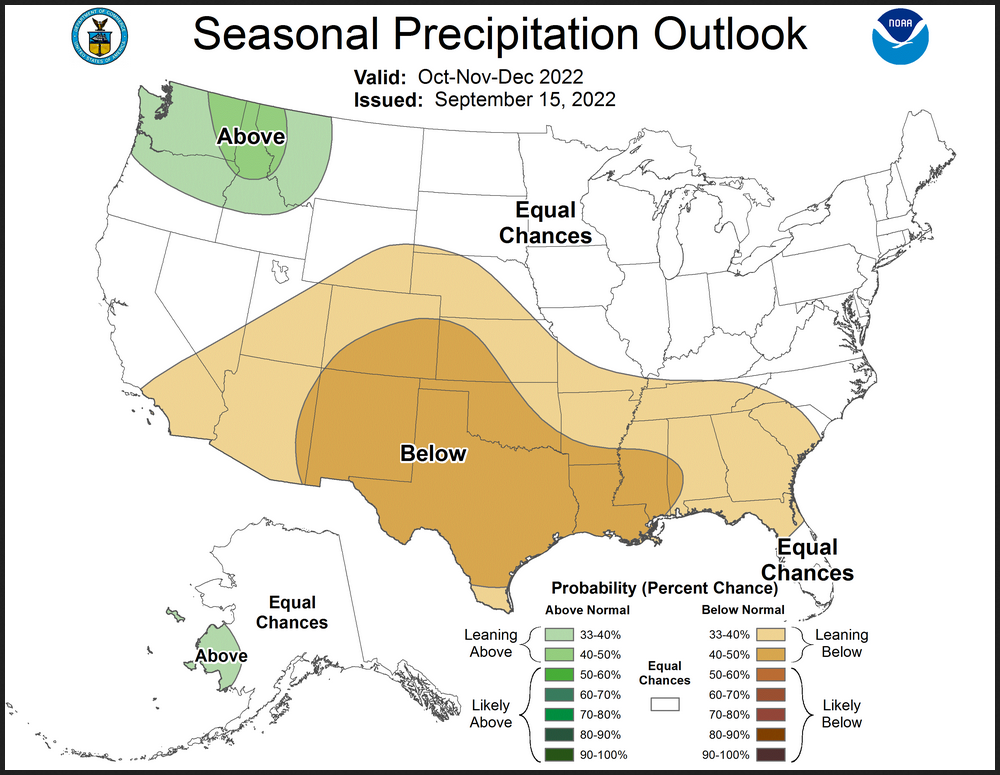

Combination Early Outlook for October and the Three-Month Outlook

The top row is what is now so-called the Mid-Month Outlook for October which will be updated at the end of September. There is a temperature map and a precipitation map. The second row is a three-month outlook that includes October. I think the outlook maps are self-explanatory. What is important to remember is that they show deviations from the current definition of normal which is the period 1991 through 2020. So this is not a forecast of the absolute value of temperature or precipitation but the change from what is defined as normal or to use the technical term climatology.

| Notice that for temperature, the October and three-month outlooks are very similar. This suggests that the November/December temperature outlook is also similar to both the October and the three-month outlook. It is almost the same situation for precipitation. |

| For both temperature and precipitation, if you assume the colors in the maps are assigned correctly, it is a simple algebra equation to solve the month two/three anomaly probability for a given location = (3XThree-Month Probability – Month One Probability)/2*. So you can derive the month two/three outlook this way. You can do that calculation easily for where you live or for the entire map. |

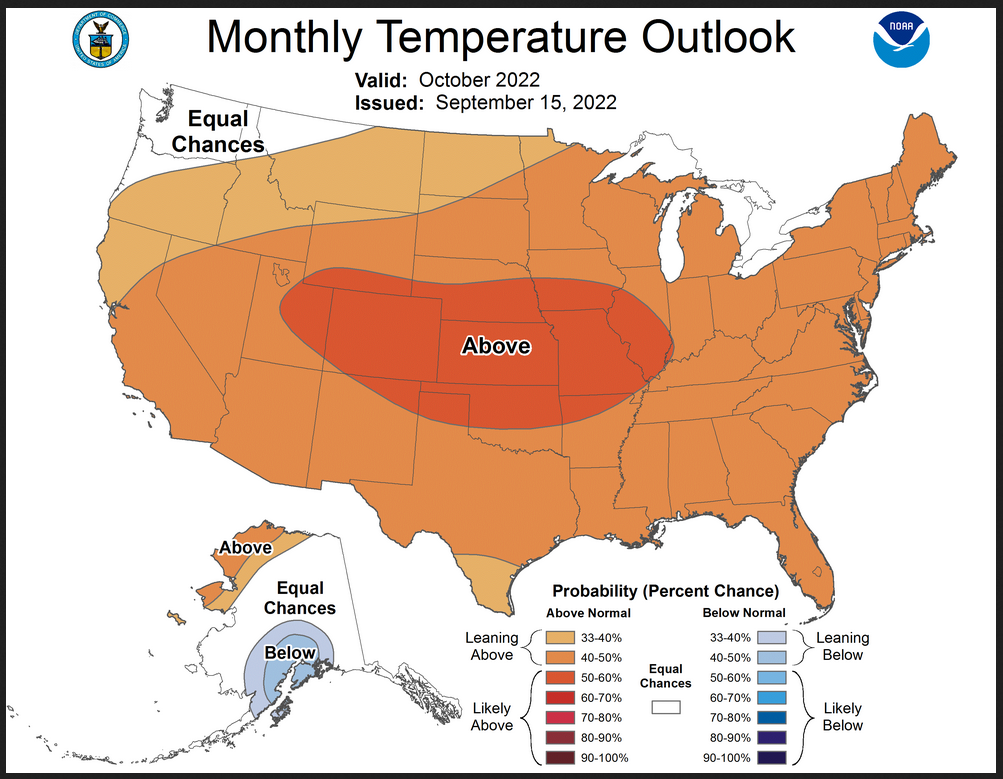

Here are larger versions of the Temperature and Precipitation outlook maps for the single month of October

The maps are pretty clear in terms of the outlook.

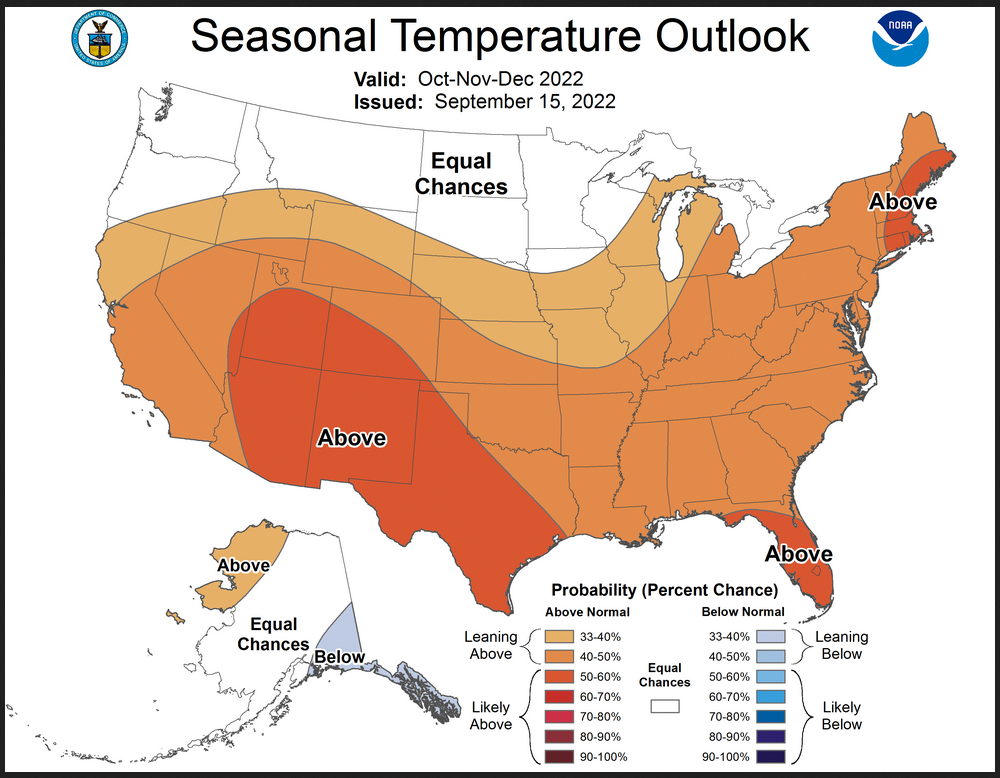

And here are large versions of the three-month OND 2022 Outlook

First temperature followed by precipitation.

The maps are larger versions of what was shown in the first graphic that had smaller versions of all four of these maps.

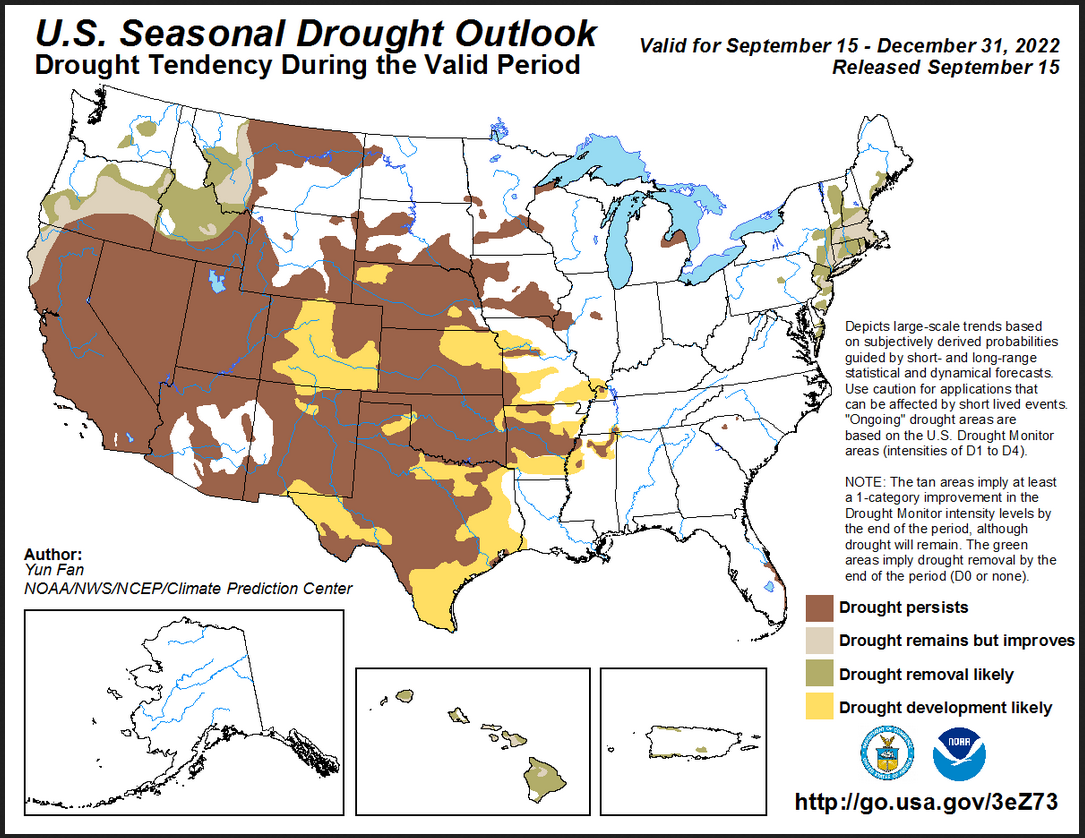

Drought Outlook

–

|

The yellow is the bad news. And this is a three-month outlook plus the remainder of September. We knew the Monsoon relief was temporary and this outlook confirms that. The lack of return of drought conditions to part of Arizona is perplexing. There is additional relief in the Northwest and Northeast. The Hawaiian Islands improve.

|

Short CPC Drought Discussion

During the past month, widespread drought relief occurred across the Four Corners region, southwestern Arizona and adjacent California, much of the Southern Plains and middle Mississippi Valley due to persistently robust monsoonal rainfall and heavy precipitation, with frequent localized flash flooding events observed in many of these areas. Periods of heavy rainfall also reversed the trend of rapid drought development across the Northeast. In contrast, episodes of extreme heat and dryness across the Northern Rockies, Northern High Plains and Central Plains caused drought expansion over these regions.

The late autumn and early winter months are a highly transitional time of year, as the wet season begins to ramp up along the West Coast. Long-term drought is likely to persist throughout much of the interior western U.S. However, an increasingly wet climatology through the late fall and early winter favors improvement across parts of Oregon, Washington, and coastal northern California. Drought conditions are also favored to continue improving across the Northeast due to a favorable time of year for soil moisture recharge. Drought persistence is favored for the north-central Midwest due to lack of a wet signal for the coming season, while drought persistence and development is favored for the southwestern Midwest with forecast below normal precipitation and above normal temperatures. All range outlooks favor drought persistence across the Great Plains, with drought development across portions of the Central and Southern Plains.

Alaska currently is drought free and is likely to continue as the region enters the cold season of the year. Removal is anticipated for any lingering drought across Puerto Rico. Drought improvement and removal is forecast for the Hawaiian Islands due to forecast near normal precipitation and the region is transitioning to its wet season.

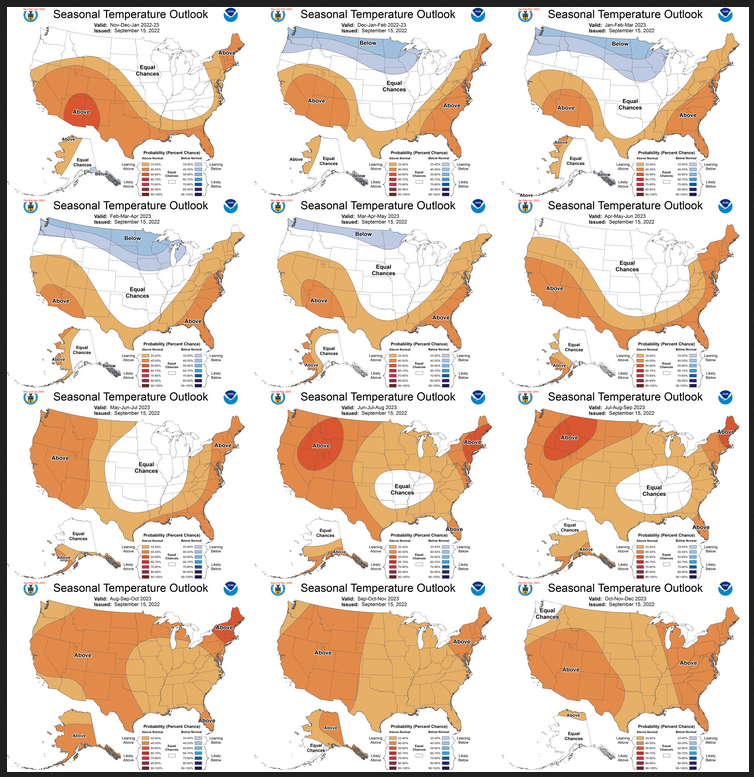

Looking out Four Seasons.

Twelve Temperature Maps

Notice that this presentation starts with November/December/January 2022/2023 (NDJ since OND is considered the near-term and is covered earlier in the presentation. The changes over time are generally discussed in the discussion but you can see the changes easier in the maps.

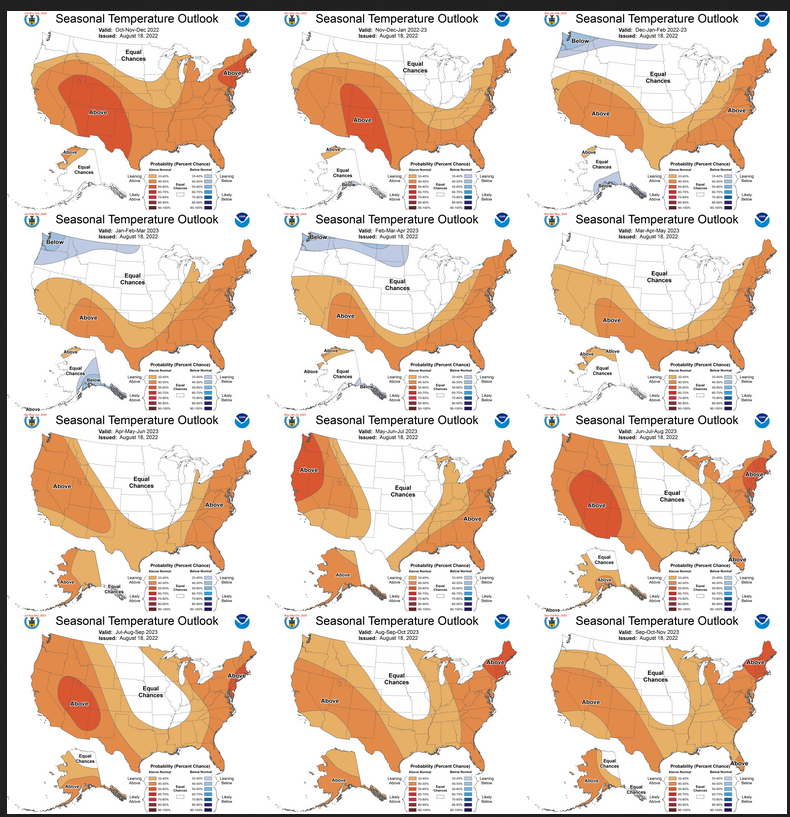

And the maps that were released last month.

| When I compare the two maps, what I see is that the new set of maps are generally similar to what was shown last month but that the Northwest cool anomaly extends into MAM 2023 and the EC anomalies in the later months are reduced in extent and totally gone by ASO 2023. I will have to read the NOAA discussion again to see why that change was made. OK, I have read it and it does not explain it. |

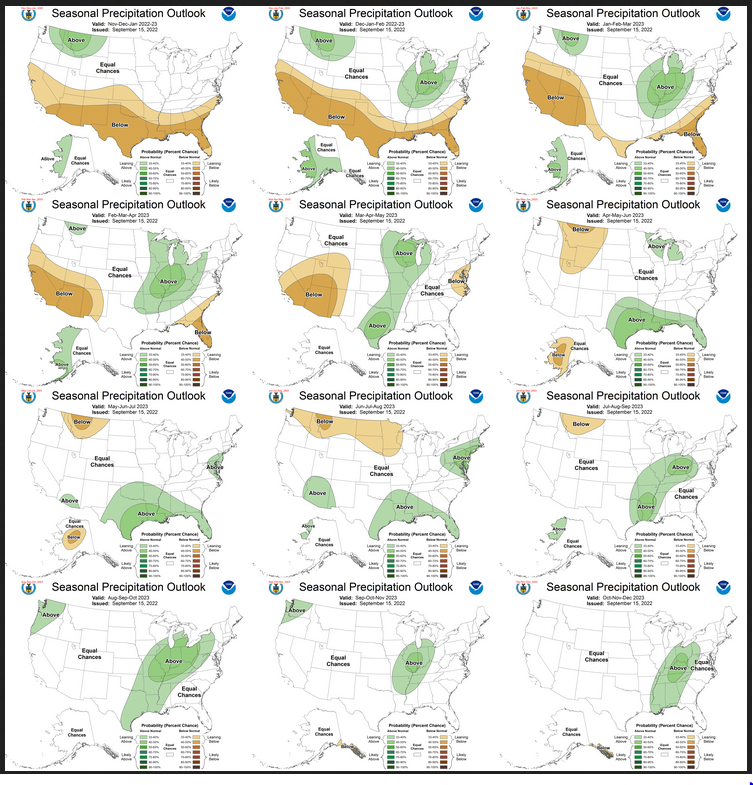

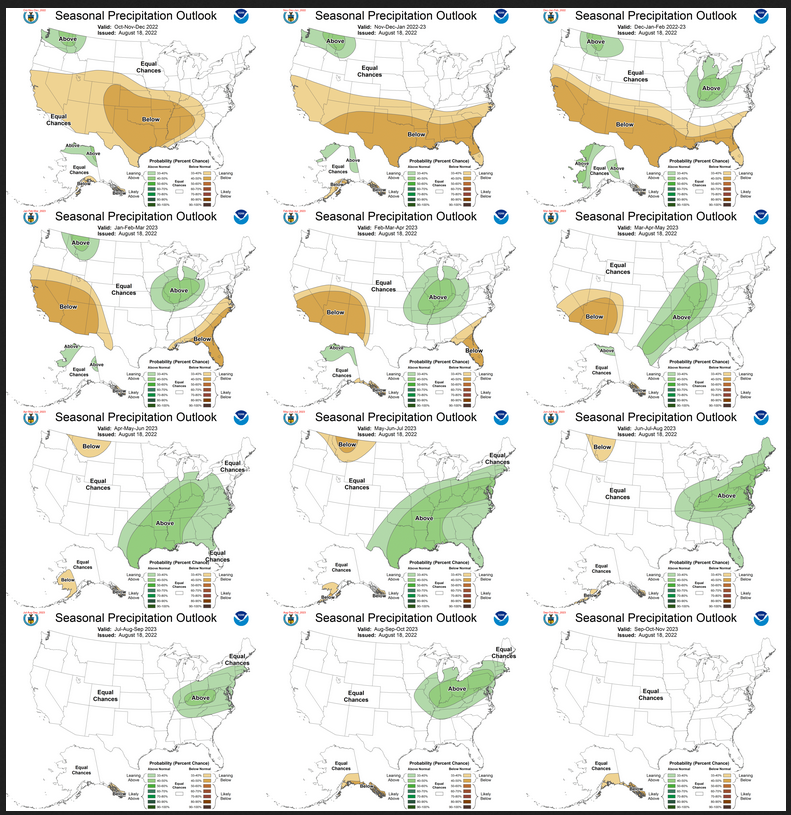

Twelve Precipitation Maps

Similar to Temperature in terms of the organization of the twelve overlapping three-month outlooks. The changes over time are generally discussed in the discussion but you can see the changes easier in the maps.

And the maps that were released last month.

| When I compare the maps, what I see is that like last month there is a major change that begins in AMJ 2023 but it is considerably different than what was shown last month. It actually looks like they are more confident in their ability to predict that far out as they even predict a better-than-average North American Monsoon. |

NOAA Discussion

Maps tell a story but to really understand what is going you need to read the discussion. I combine the 30-day discussion with the long-term discussion and rearrange it a bit and add a few additional titles (where they are not all caps the titles are my additions). Readers may also wish to take a look at the article we published last week on the NOAA ENSO forecast. That can be accessed here.

I will use bold type to highlight some things that are especially important. My comments, if any, are enclosed in brackets [ ].

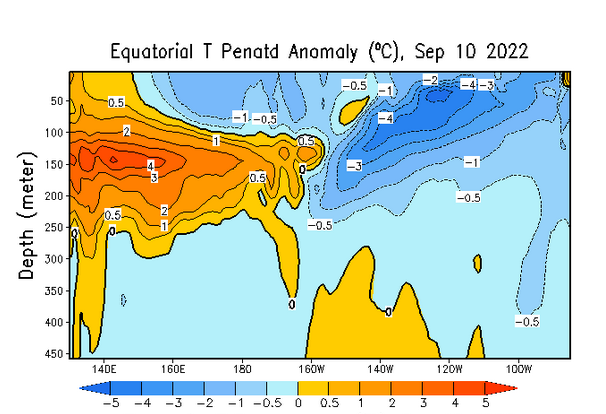

CURRENT ATMOSPHERIC AND OCEANIC CONDITIONS

The coupled oceanic and atmospheric observations reflect La Niña conditions. During August 2022, La Niña continued with below average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) persisting in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific Ocean. In the last week, all of the Niño index values ranged from -1.1°C to -0.7°C. Negative subsurface temperature anomalies (averaged from 180-100°W) were mostly unchanged during the month, reflecting the dominance of below-average temperatures across the eastern Pacific Ocean. Low-level easterly wind anomalies and upper-level westerly wind anomalies continued across most of the equatorial Pacific. Convection and rainfall remained suppressed over the western and central tropical Pacific and enhanced over Indonesia. Overall, the coupled ocean-atmosphere system continued to reflect La Niña.

The Real-time Multivariate Madden Julian Oscillation (RMM) index and upper-level velocity potential anomaly analyses indicate a weakened and incoherent Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO) during the past week. Although weak, continued eastward propagation of the intraseasonal signal is evident in both the observation and forecast fields, where dynamical models depict a potential strengthening of the MJO over the western Hemisphere, Africa and Indian Ocean.

PROGNOSTIC DISCUSSION OF SST FORECASTS

The most recent International Research Institute (IRI) for Climate and Society plume forecast of the Niño-3.4 SST index indicates La Niña will persist into the Northern Hemisphere winter 2022-23. There is an interesting split in the dynamical versus statistical model forecasts, with the latter set suggesting La Niña will persist longer, through JFM 2023. At this time, the forecaster consensus sides with the statistical models, although there is still large uncertainty over how long La Niña will last and when it will transition to ENSO-neutral (56 percent chance of a transition to ENSO-neutral during February-April 2023). In summary, La Niña is favored to continue through Northern Hemisphere winter 2022-23, with a 89 percent chance in OND, decreasing to a 54 percent chance in JFM 2023.

30-DAY OUTLOOK DISCUSSION FOR OCTOBER 2022

A review of background climate conditions continues to show established La Nina conditions which are forecast to remain in place at least into the upcoming winter months. Both the Nino4 and Nino3.4 latest sea surface temperature (SST) values remain near -1.0 degrees C and tropical atmospheric conditions (i.e., convection/rainfall, low-level and upper-level winds) continue to be consistent with La Nina. Although this is a monthly outlook and impacts from La Nina to the mid-latitudes are generally weak at this time of the year, the La Nina base state was considered in the October monthly outlook to some degree.

The MJO signal is not particularly coherent especially in certain indices such as the RMM index which is being heavily influenced by interference from ongoing La Nina conditions. Some predictions of other variables such as 200-hPa velocity potential show some potential for more MJO organization as we enter the month of October with the enhanced convective phase located in Phases 1-2-3. This may promote enhanced convection to develop in the Central America and Caribbean region at a time of the year when primary tropical cyclone development begins to shift from the eastern and central Atlantic westward to these areas.

In addition to the considerations noted above, dynamical model guidance from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME), Copernicus model suite (C3S) and extended (30-day) ensemble model systems from the CFS, ECMWF and GEFS that target the Week 3-4 period were utilized in preparing the outlook.

Temperature

The October 2022 temperature outlook depicts favored above-normal monthly mean temperatures for the majority of the CONUS with the only exception being the far Pacific Northwest. The greatest odds are forecast for an area from the central Rockies to the central Plains where the anomalously warm signal was most consistent amongst all the forecast tools and potential La Nina influence. The Week 3-4 dynamical model guidance and multiple linear regression forecast tool (ENSO, MJO, trend as predictors) supported a warmer than average start to October across the CONUS associated with forecast ridging and northward shifted westerlies. For Alaska, the signals overall were quite weak and conflicting. Slight tilts toward above-normal (below-normal) temperatures are depicted for coastal northwest Alaska (south-central Alaska) driven primarily by long-term trends (model guidance).

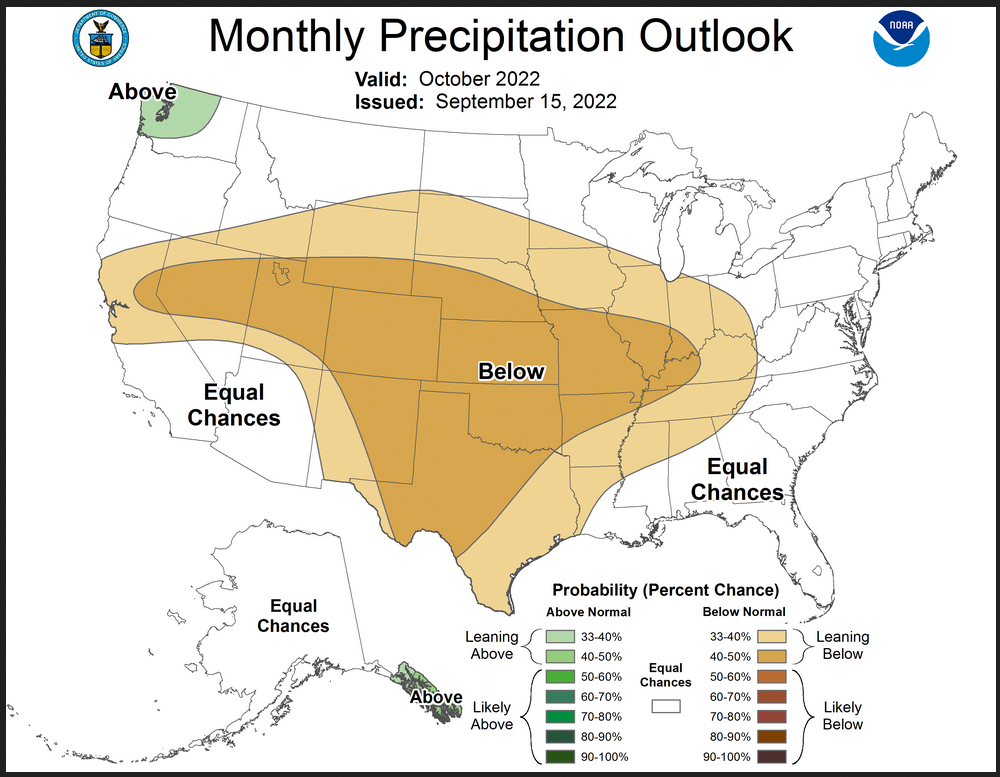

Precipitation

For the October 2022 precipitation outlook, elevated odds for below-normal monthly total precipitation amounts is depicted from north-central California eastward across the central Rockies to the central and southern Plains and parts of the central Mississippi and Ohio Valley’s. The La Nina base state, dynamical model guidance and long term trends contributed to this outlook. A slight tilt toward above-normal precipitation is shown for parts of Washington and the Alaska panhandle associated with model guidance and potential La Nina impacts. Probabilities in all locations are modest due to the low predictability common during this time of the year.

Tropical

Considerations of tropical moisture from the Gulf of Mexico or Caribbean Sea region related to any potential intraseasonal influence noted above resulted in an Equal Chances (EC) forecast for parts of the Gulf coast and Southeast despite considerable forecast guidance favoring drier-than-normal precipitation. There were weak and conflicting signals for mainland Alaska so EC is currently forecast in this area.

SUMMARY OF THE OUTLOOK FOR NON-TECHNICAL USERS (Focus on October through December)

La Niña conditions are present, as represented in current oceanic and atmospheric observations. A continuation of La Niña is likely through the Northern Hemisphere Winter 2022-23, with an 89 percent chance during October-November-December (OND) decreasing to a 54 percent chance for January-February-March (JFM). Conversely, the chances of El Niño are exceedingly small, with probabilities less than 3 percent through the upcoming winter.

Temperature

The OND 2022 temperature outlook favors above normal temperatures for the southern two-thirds of the Contiguous United States (CONUS), the eastern third of the CONUS, and northwestern Alaska. The largest probabilities (greater than 50 percent) of above normal temperatures are forecast across the Four Corners Region, much of the Southwest, the Rio Grande Valley, much of the Southern Plains, the Florida Peninsula, and eastern New England. Conversely, a weak tilt toward below normal temperatures is indicated for southeastern Alaska.

Precipitation

The OND 2022 precipitation outlook depicts enhanced probabilities of below normal precipitation amounts across the Southern Tier of the CONUS extending northward to include much of the Central Plains and Central Rockies. Above normal precipitation is more likely for the northwestern CONUS and parts of southwestern Mainland Alaska. Equal chances (EC) are forecast for areas where probabilities for each category of seasonal mean temperatures and seasonal accumulated precipitation amounts are expected to be similar to climatological probabilities.

BASIS AND SUMMARY OF THE CURRENT LONG-LEAD OUTLOOKS

PROGNOSTIC TOOLS USED FOR U.S. TEMPERATURE AND PRECIPITATION OUTLOOKS

Dynamical model forecasts from the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME), the Coupled Forecast System Model Version 2 (CFSv2) , the Copernicus (C3S) multi-model ensemble system were used extensively for the first six leads when they are available, as was the objective, historical skill weighted consolidation and Calibration, Bridging, and Merging (CBaM) guidance, that combines both dynamical and statistical forecast information.

Additionally, the official ENSO forecast depicts probabilities of La Niña that are significantly higher than climatological probabilities through the upcoming winter. This anticipated La Niña signal played a role in the construction of these outlooks. At later leads, decadal trends in temperature and precipitation were increasingly relied upon in creating the seasonal outlooks.

PROGNOSTIC DISCUSSION OF OUTLOOKS – OND 2022 TO OND 2023

TEMPERATURE

Above normal temperatures are favored throughout a majority of the southern and eastern CONUS and northwestern Alaska during OND. Conversely, below normal temperatures are more likely for southeastern Alaska. EC of below, near, or above normal temperatures are forecast for the northwestern and north-central CONUS. This EC area is due to weak or conflicting signals among temperature tools. Probabilities of above normal temperatures are reduced relative to last month across the northern CONUS due to a trend toward a colder solution in the temperature consolidation coupled with a cold La Niña signal across parts of the Northern Plains and Northwest. Above normal temperatures remain likely (greater than 50 percent) from the Four Corners Region to the Southern Plains as well as for the Florida Peninsula and eastern New England, due to good agreement among both dynamical and statistical guidance. Guidance has trended colder across much of Alaska relative to last month. Thus, increased probabilities of below normal temperatures were introduced to southeastern parts of the state, which is also consistent with natural analogs from the current ENSO state.

From November-December-January (NDJ) through March-April-May (MAM), impacts from the ongoing La Niña continue as above normal temperatures are favored across the Southern CONUS and the Eastern Seaboard while enhanced below normal temperature probabilities persist across southeastern Alaska and expand southward to the northwestern and north-central CONUS by December-January-February (DJF). After MAM, the forecast pattern increasingly begins to reflect trends with above normal temperatures generally favored across most of the southern, western, and eastern CONUS next spring and expanding to most of the remainder of the CONUS next summer and into the fall. Probabilities of above normal temperatures peak across the interior Northwest next summer and across the Northeast next summer into early fall consistent with trends . Across Alaska, above normal temperatures are most likely for western parts of the state during the Spring, shifting to the South Coast during the summer months, and eventually expanding northward to northern parts of the state by next fall.

PRECIPITATION

Model guidance remains consistent from previous months depicting elevated probabilities of below normal precipitation for much of the southern CONUS, and increased chances of above normal precipitation for the Pacific Northwest during OND. Models have trended toward an expansion of the dry signal eastward across the Southeast relative to last month, with influences from potential tropical disturbances decreasing and La Niña influences increasing as we progress deeper into the fall and early winter. Conversely, precipitation guidance has trended wetter across the northwestern CONUS, resulting in an increase in above normal precipitation probabilities relative to last month. A slight tilt toward above normal precipitation is indicated for parts of southwestern Alaska, based primarily on dynamical model guidance from the CFSv2 and a wet signal derived from natural analogs to the current ENSO state. EC is indicated for most of the rest of the forecast domain as signals for the various dynamical and statistical tools are too weak or conflicting to issue a forecast with a sufficient degree of confidence.

As we progress further into late fall and through the winter, dynamical and statistical guidance persist with a dry signal across the southern CONUS, consistent with a La Niña signature. An eastward progression of enhanced above normal precipitation probabilities is noted across the northwestern CONUS, peaking in coverage during the late fall and through the winter months. A wet signal is also favored to expand southward from the Great Lakes across much of the east-central CONUS during the winter and early spring, consistent with La Niña composites. During next spring through next fall, trends become the dominant factor with increased chances of above normal precipitation generally indicated across parts of the east-central CONUS and Gulf Coast Region for much of the period. Conversely, trends favor a dry pattern for much of the Southwest during early spring shifting northward to the Northern Rockies by late Spring, with increased chances of dryness for parts of the Northern Plains next summer as well. As dryness potentially expands into the northern Plains next summer, a corresponding weak tilt toward above normal precipitation makes a brief appearance for parts of the Southwest Monsoon Region during May-June-July (MJJ) and June-July-August (JJA), consistent with recent trends . Thereafter, an area of slightly enhanced probabilities of above normal precipitation is indicated across the Pacific Northwest in August-September-October (ASO) and September-October-November (SON), based primarily on statistical guidance from trends and ENSO. There exists high uncertainty across much of Alaska with large areas of EC indicated. However, dynamical guidance supports increased odds of above normal precipitation across parts of the western Mainland through the February-March-April (FMA) season. Conversely, statistical guidance from trends and ENSO support a slight tilt toward below normal precipitation for parts of the southwestern and central Mainland Alaska late in the spring into the early summer. Thereafter, trends support slightly increased chances for above normal precipitation for parts of the northwestern Mainland next summer and slightly increased chances of below normal precipitation for parts of the Panhandle next fall.

Review of the ENSO Assumptions utilized by NOAA (CPC) in Preparing this Four-Season Outlook

It is useful to review the ENSO forecasts used by NOAA to produce this Four-Season Outlook. We reported on that last week and you can read that article by clicking here

The key information used by NOAA follows.

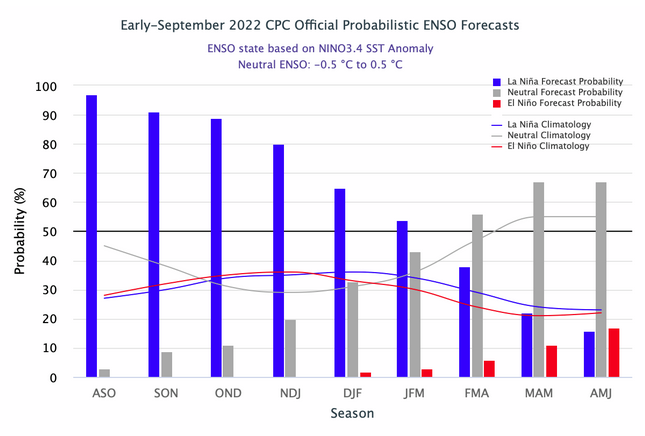

IRI CPC ENSO STATE Probability Distribution (IRI stands for the International Research Institute for Climate and Society)

Here are the new forecast probabilities. This information is released twice a month and the first release is based on a survey of Meteorologists, the second is based on model results. The probabilities are for three-month periods e.g. ASO stands for August/September/October. I am just showing the first release which is what we have and presumably what NOAA (actually their CPC Division) worked from.

| Notice for JFM 2023 the probability of La Nina and ENSO Neutral is no longer equal. But for FMA the probability for ENSO Neutral exceeds that for La Nina. So maybe March is when the ocean conditions will be consistent with ENSO Neutral but the impact on our weather may lag a month or so. So we really seem to be looking a La Nina into Spring. This is a very slight change from the analysis made last month. NOAA refers to a difference between the dynamic models and the statistical models which show the transition to be slightly later and NOAA leans towards the statistical models as per their discussion. |

–

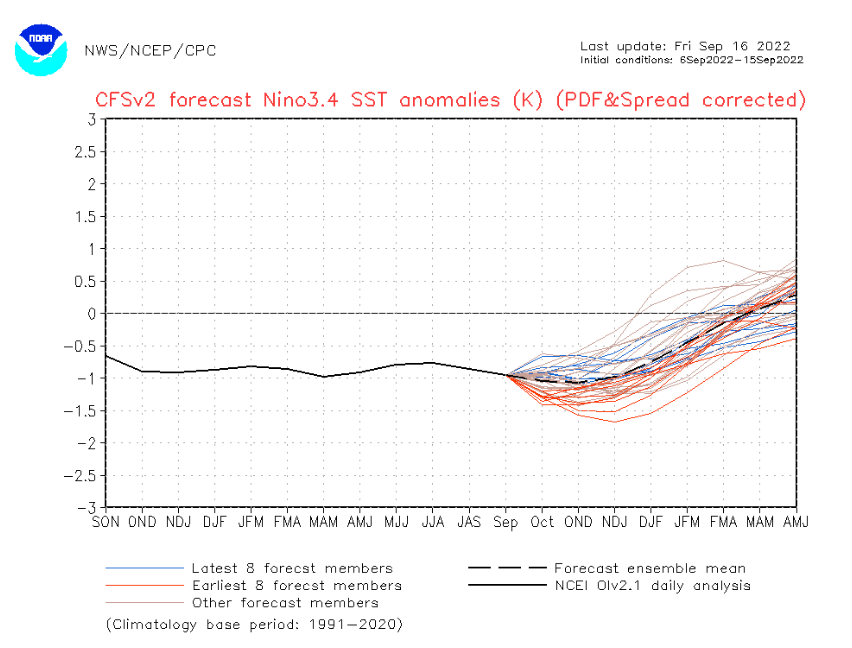

| The above will not auto-update. But the image will update if you click HERE. https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/people/wwang/cfsv2fcst/images3/nino34SeaadjPDFSPRDC.gif

NOAA relies more on the IRI Forecast. But perhaps this model is now showing that we may become ENSO Neutral in late winter. It is a dynamical rather than a statistical model so it is in line with what NOAA is saying. |

Resources

The link for the drought outlook map and some discussions that come with the map can be found by clicking HERE.

| I hope you found this article useful and interesting. |